Timber, glamping and a rare mushroom may be on a collision course in one of the Columbia River Basin’s Wild and Scenic Rivers

Turbulence ahead: Many forces are at play along the White Salmon River. Photo by Jane Chorazy, USFWS

By Dac Collins. May 28, 2020. When it comes to discussing their picking spots, most mushroom hunters share a trait with the fruiting fungal bodies they pursue. They’re a secretive breed.

So it came as no surprise last fall when Dr. Michael Beug, one of the Pacific Northwest’s leading mycologists and a professor emeritus at the Evergreen State College, said he was unable to describe exactly where he discovered a new species of mushroom. Only that he’d found it while walking in the woods on the east bank of lower Spring Creek—an area that falls within the National Wild and Scenic Corridor of the Lower White Salmon River and is privately owned by the SDS Lumber Company.

To appreciate the significance of Beug’s discovery—a magical-trumpet-looking species that, in his estimation, could be a relative of the black chanterelle—it’s important to recognize that the combination of aforementioned factors (a Wild and Scenic Corridor on private land) puts the patch of forest where he made it in a unique and troubled position.

Privately owned public treasure

Congress created the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System in 1968 “to preserve certain rivers with outstanding natural, cultural and recreational values in a free-flowing condition for the enjoyment of present and future generations.”

When the White Salmon River was brought into the National Wild and Scenic Rivers System in 1986, it was recognized for possessing five “outstandingly remarkable values” (ORVs): whitewater boating, geology, hydrology, cultural resources and, perhaps most importantly, the river’s namesake: fish.

The designation gave the waterway federal protection under the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act. First and foremost, the Act prohibits the construction of dams and “other in-stream activities that would harm the river’s free-flowing condition, water quality or outstanding resource values.”

Mushroom man: Dr. Michael Beug on the hunt in “a particularly beautiful piece of woods.” Photo by Jurgen Hess

It also gave the river an administrator—a managing agency—responsible for protecting and enhancing its exceptional assets. Because of the White Salmon’s proximity to the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area, Congress chose the United States Forest Service (USFS) as the lead agency to implement the Lower White Salmon National Wild and Scenic River Management Plan of 1991.

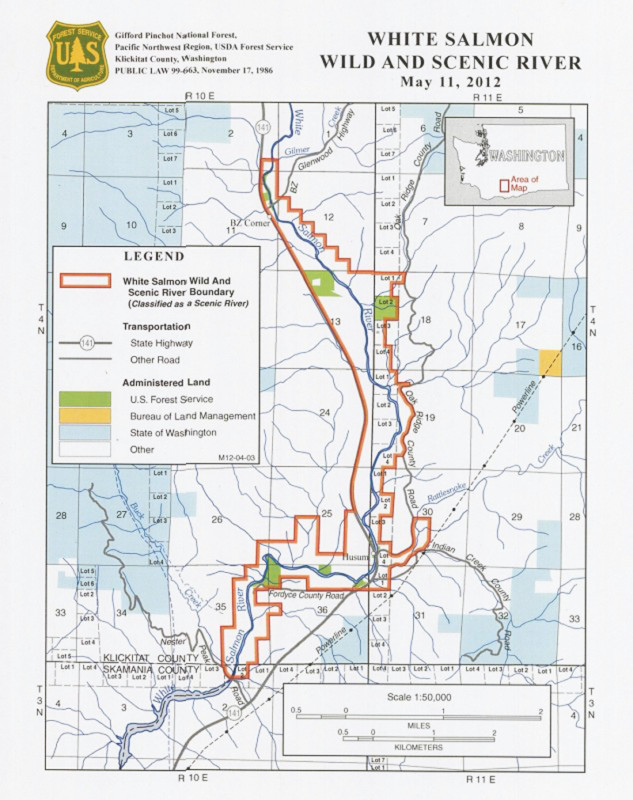

A major part of that Management Plan was setting boundaries for the area to be managed.

With input from Klickitat and Skamania counties, Washington State, the Yakama Nation, local residents and private landowners, the USFS adopted boundaries for the Wild and Scenic Corridor of the Lower White Salmon. That corridor, which totals 1,874 acres, stretches 7.7 miles south from Gilmer Creek to Buck Creek.

But there are a handful of other tributaries that feed this stretch of river. One of these, Spring Creek, was recognized then—as it is now—for both its resident fish populations and its potential as a vital habitat for the spawning and rearing of anadromous fish.

Although Condit Dam was still blocking the passage of salmon and steelhead back in 1991, adult salmon have been observed in lower Spring Creek since the dam’s removal in 2011. In the 2018 Klickitat County Lead Entity Salmon Recovery Strategy, Spring Creek is listed as a priority watershed that provides spawning and rearing habitat.

Precisely because of its value to native fish populations, the boundaries of the Wild and Scenic River Corridor were amended to include the lower reaches of Spring Creek.

White Salmon Wild and Scenic River Plan shows the protected corridor (in red) along river. Courtesy of U.S. Forest Service

As its name implies, the spring-fed creek flows year-round, adding cold, clean water to the glacially charged flow of the White Salmon. Because it has shallow riffles and broad gravel beds, as well as coarse woody debris and a healthy, second-growth forest shading it, the creek is now frequented by spawning salmon during fall months … the same time of year when most wild species of mushroom fruit.

In fact, it was November when Beug discovered what he believes is a new species of mushroom near the east bank of lower Spring Creek.

Beug has been involved with the research, identification and discovery of new species of fungi for most of his career.

A former president of the Pacific Northwest Key Council, he’s written a number of magazine articles about fungi and is the co-author of Ascomycete Fungi of North America. In the last 12 years alone, he’s identified 50 new species of fungi in the Columbia River Gorge.

Rare mushroom find

Beug lives off Spring Creek Road on a piece of property he’s owned since 1979. He moved there full-time after retiring from Evergreen State College in 2001. Since then, he’s become intimately familiar with the neighboring forest that surrounds the lower reaches of Spring Creek.

“It is a particularly beautiful piece of woods,” he says. “Just a very, very peaceful place to walk. I’ve been picking chanterelles there for a good 20 years now.”

Beug has been able to pursue his passion because for the past two decades (perhaps longer) SDS Lumber Company, headquartered in Bingen, Washington, has allowed the public to freely access the privately owned forest on foot.

“It was just before Thanksgiving,” Beug says. “I went in to pick a few chanterelles for dinner, and to see what else was up … and here was this beautiful little surprise.”

Fungal find: Michael Beug has identified some 50 new fungi species in the Gorge. But this one was new to him. Photo by Michael Beug

Beug says he immediately recognized the mushroom’s similarities with the prized black chanterelle, also known as Craterellus calicornucopioides. Sought after by chefs and foodies around the world, black chanterelles have earned a reputation, as well as a few nicknames, including “Horn of Plenty” and “poor man’s truffle.”

“They literally look like a clump of miniature trumpets stuck in the ground,” he explains, referring to the Craterellus genus. “But this one was sort of a greenish-yellow color, not a black one.”

He harvested a sample and shared photos of the mushroom with colleagues around the country. They hadn’t seen anything like it before.

Beug is still awaiting genetic testing results, which will be the definitive answer as to whether the mushroom is indeed a unique species or simply a “color morph” of Craterellus calicornucopioidies. Either way, he says, the discovery is “something that anyone who knows anything at all about mushrooms would be very excited about.”

“Even if it is calicornucopioidies, it’s an incredibly rare mushroom in this area that’s incredibly delicious and very valuable,” he says.

Ominous signs

It wasn’t until April of this year that Beug made another important discovery in the forest around lower Spring Creek. He noticed SDS had taken down its original private property signs—which permitted public foot traffic but prohibited motor vehicles—and replaced them with signs that simply read: NO TRESPASSING.

A number of other local residents also noticed the change in signage, as well as flagging on some of the trees. Word spread through the small community and assumptions quickly formed: SDS was preparing to log the forest.

SDS has not responded to multiple requests for comment from Columbia Insight, however, and the company’s plans for the Spring Creek forest remain unclear.

“We have not seen an official application from SDS yet,” says Whitney Butler, a forester with the Washington Department of Natural Resources, adding that he’s aware of local speculation about possible logging. “Until we see an official application through the Department of Natural Resources, it’s all speculation at this point.”

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]A contentious history with SDS helps explain the local community’s cause for concern.[/perfectpullquote]

But Beug and others who are concerned for the health of the forest believe they have every right to speculate. SDS is a timber company, after all, and timber companies are in the business of cutting down trees. Just as mycorrhizal mushrooms—a class of fungi that includes Craterellus—are in the business of sustaining them.

“There’s the litter decomposers, the wood decomposers, and there’s the mycorrhizal fungi,” Beug says, referring to the different types of mushrooms found in Northwest forests. “And all of those are critical parts of the forest ecosystem as we see it.

“Mycorrhizal fungi are important to the tree in terms of supplying minerals and water. And the trees are important to the fungi in terms of supplying the carbohydrates that the fungi need to grow and thrive.

“If you take, for example, a Douglas fir tree, and you try to grow it in healthy soil that has its full range of bacteria but no fungi, the tree will barely grow. So these mycorrhizal fungi are critical for the health of our forests and the vigor of our trees.”

Those trees, of course, fulfill essential services for the streams themselves. They contribute nutrients, woody debris and shade, and they reduce erosion while filtering out sediment and pollutants from stormwater runoff. All of this ultimately benefits the aquatic species that live in the creek, especially the salmon that spawn and die there, providing nutrient-rich salmon carcasses to fertilize the trees that will shade the creek for the next generation of fish.

Take out the trees and it all breaks down.

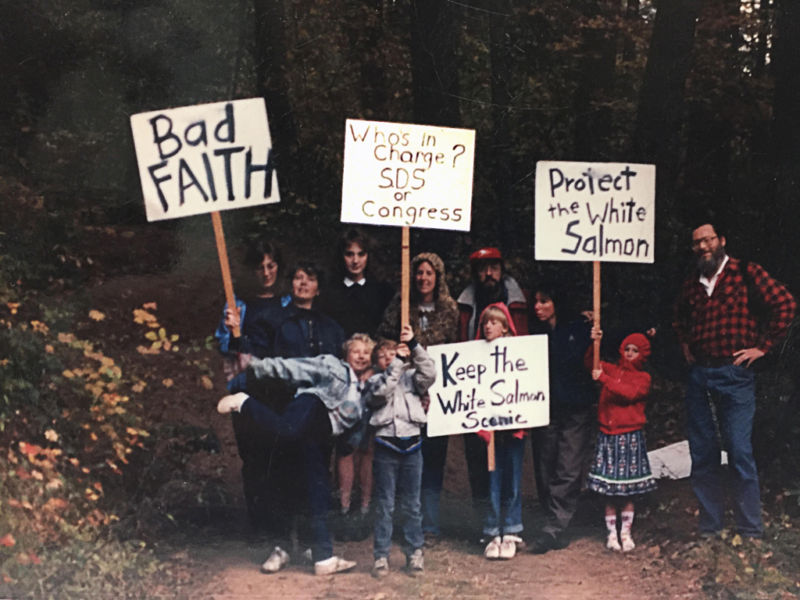

History of White Salmon River protest

The local community understood as much back in 1988.

In that year a group led by the Friends of the White Salmon organized to stop SDS from logging in the Spring Creek area. They protested on-site, and they picketed the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area office in nearby Hood River, imploring the Forest Service to intervene.

Eventually the USFS did step in, sending a cease and desist letter to SDS.

Initially, SDS complied with the letter. But years later, when the dust-up between local residents and the lumber company had settled, they logged the forest anyway, harvesting every conifer that stood between Spring Creek Road and the earthen dam that sits upstream of the road.

Among its more vocal members is Dennis White—one of the original instigators of the 1988 Spring Creek Standoff—who says he fears “SDS is back at Spring Creek to perform their final solution.”

The Columbia Gorge Audubon Society’s Washington conservation chair, White has fought for the protection of the White Salmon River for over 30 years. Along with his wife, Bonnie, and other residents of the Trout Lake Valley, he co-founded Friends of the White Salmon River in 1976 when the river was being threatened by hydropower development. He was directly involved with efforts to add the White Salmon River—and also the nearby Klickitat River—to the National Wild and Scenic River System.

Long haul: Friends of the White Salmon River have been active since 1976. This group gathered to oppose logging in 1988. Photo courtesy of Dennis White

Representing the Columbia Gorge Audubon Society, White joined with WildEarth Guardians and Advocates for the West, a public interest law firm, in sending an April 22 letter to Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area manager Lynn Burditt.

“The Forest Service is falling short of its duties to protect and enhance the ORV’s of the [Wild and Scenic] White Salmon,” the letter reads.

It explicitly calls out the USFS for failing to implement and revise the original 1991 Management Plan. It says the Service’s plan faced a major hurdle from the start because all of the land within the Wild and Scenic Corridor was privately owned at the time the corridor was designated. And 40 percent of it was owned by a single entity: the locally owned SDS Lumber Company.

In fact, the USFS came up with a way to bring some of this private land into public ownership: a three-way land exchange between the USFS, the Washington Department of Natural Resources and SDS.

“It is important to remember that the (public) acquisition of SDS Lumber Company lands through exchange is one of the key features in making this a workable plan,” reads the 1991 Management Plan.

But the land exchange never happened. SDS still owns approximately 40 percent of all lands within the Wild and Scenic Corridor.

In the time since the land exchange fell through, the Forest Service has acquired a total of 144 out of a potential 770 acres. (Because the Wild and Scenic Rivers Act recognizes that “in most cases, not all land within boundaries is, or will be, publicly owned,” it encourages the lead agency to acquire land within the corridor by working with private sellers on a willing basis. However, the Act limits the federal government to acquiring no more than 100 acres per river mile.)

The 1991 Management Plan also stipulates the USFS will revise its plan every 10 to 15 years. But as the letter to Burditt points out that hasn’t happened either.

“The River Plan provided that it ‘will ordinarily be revised on a 10-year cycle, or at least every 15 years.’ The River Plan also anticipated a revision if anadromous fish were reintroduced above the Condit Dam site or if the Upper White Salmon River was designated under the Act—events that occurred years ago,” reads the local coalition’s April 22 letter. “The agency’s failure to update the plan nearly thirty years later and after these major events is an egregious delay. By failing to fully implement and timely revise its River Plan, the Forest Service is falling short of its obligations under the Act.”

Neither Burditt nor the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Office has yet responded to multiple requests for comment from Columbia Insight for this story. [A representative of the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area Office has since contacted CI. —Ed.]

Enter glampers

Meanwhile, roughly five miles upriver from the confluence of Spring Creek and the White Salmon River, a controversial land sale by another private timber company is moving forward.

In the time since Columbia Insight reported on this story in November 2019, Under Canvas, which calls itself “the nation’s premier glamping and luxury camping experience provider,” has been in talks with the Weyerhaeuser timberland company to purchase approximately 120 acres off of Oak Ridge Road—30 of which fall within the Wild and Scenic Corridor.

READ more on CI: United by a river, divided over management

Under Canvas chief development officer Dan McBrearty confirms the property is currently under contract.

“With this proposed project Under Canvas would provide a seasonally operated, upscale overnight campground with individual canvas tents for sleeping quarters,” McBrearty says.

McBrearty says camping would be available from April through October, and that “because of our commitment to a minimal footprint, the majority of the site would be retained as open space/natural land.”

“No access to the White Salmon River is proposed as part of the project, and the camp will be sited to ensure no ecological or aesthetic impact to the river and its buffer,” McBrearty says.

But White, who has been trying to convince the Forest Service to acquire the Weyerhaeuser tract—or at least the 30-acre portion that straddles the Wild and Scenic Corridor—sees a purchase by Under Canvas as a step in the wrong direction, since it would preempt any option of public acquisition by the Forest Service.

All over Under: Ad hoc signage has appeared near the White Salmon River. Photo courtesy of Dennis White

White calls Under Canvas “a motel complex masquerading as camping,” and its potential development “just another example of the U.S. Forest Service letting private interests set the management agenda.”

“This is not just an impact on the physical environment and the Wild and Scenic River Corridor,” White says. “It’s an impact on people’s lives. All that infrastructure … water, sewage, utilities, parking lots. This commercialization is going to change the entire complexion of the river valley.”

White says a group of neighboring landowners and local residents is organizing to oppose the purchase by Under Canvas.

Columbia Insight has received a number of emails from members of this community. (Columbia Insight has vetted these comments and agreed to their authors’ request to remain anonymous.) The emails express concern about increased traffic on the rural road, as well as “the possibility of wildfire caused by campfires at the glampground.”

Locals also say the Under Canvas project would be incompatible with the customary agricultural uses along Oak Ridge Road. There are a number of orchards located off the road and the area is still open rangeland.

Because of this incompatibility, Under Canvas is unable to move forward without securing a Conditional Use Permit from Klickitat County. Opponents of the project worry approval of the permit will “set a precedent for unrestricted commercial development along the eastern bank of the White Salmon River.”

“The water needed for a resort of this scale will severely exacerbate the lack of water resources for our farms, orchards and ranches,” writes one resident, referring to the 90-100 sites currently proposed by Under Canvas.

“The traffic and the negative environmental impact are not worth what this company wants to do,” writes another. “They say they’re cognizant of neighbors’ needs and desire to maintain peace, but to think that an enterprise like this has anything but dollar signs in their sights is foolhardy.”

Apparent decisions by SDS and Forest Service not to defend their positions is noteworthy. For SDS, it’s understandable: What would they say? “’Yea, we’re gonna cut down Spring Creek.’ ‘Yea, it’s a Nat’l Scenic River.’ ‘So what?’ ‘That’s what the owners of SDS pay us to do: Generate capital and employ people.’ ‘To do otherwise would put us at market disadvantage.’” Capitalism makes no exception for Wild & Scenic Rivers.

The Forest Service, the “river keeper”, provides the check on market forces. Right? Wrong!! No excuses for silence here. The Forest Service is a “public” agency staffed by public servants paid with checks written out by the taxpayers. The agency has been caught with its pants down. Embarrassed? Then do better. The truth is, the Forest Service has stolen–squandered certainly–the promise of river protection given to us by Congress. The on-going SDS story reflects the utter failure of the agency to do its job. The real story here: Congress discarded the Nat’l Park Service for the Forest Service, an agency better suited to staking out timber sales and fighting fires than protecting America’s special places. The agency is simply unwilling do the job. The historical ties to the timber industry shine through with SDS and Weyerhaeuser on the White Salmon.

It’s past time for the environmental big players to step up and broker the SDS-Forest Service trade/buy out or watch the slow death of a nationally designated river. Logging now–development later. The Stevensons are not going to wait for another tree growth cycle. Conservationists, understand, you will own this one way or the other, the legacy here is going to be collective. Read Advocates for the West’s letter, it lays the problem bare. Go to: https://wildearthguardians.org/press-releases/forest-service-turns-its-back-on-white-salmon-river/ and follow the highlighted link.

“Independent,” said the Seattle propaganda merchant. LOL