As hydropower debates rage, tribes in the Upper Columbia River Basin are working to reintroduce salmon to local rivers

August presence: Spokane tribal elder Pat Moses releases a salmon into the cool waters of the Little Spokane River. Courtesy of Inland Northwest Land Conservancy

By Eli Francovich, September 9, 2021. On hazy day in August, Spokane tribal leaders released 51 summer chinook into the Little Spokane River, the first time salmon have been in those waters in 111 years.

The fish, ranging from seven to 18 pounds, arrived in the back of a truck, driven from the tribe’s hatchery near Chelan, Wash. They passed through north Spokane’s urban sprawl to the river valley.

Once on the edge of the Little Spokane River—which eventually joins the main stem of the Spokane, which in turns dumps into the Columbia River—the fish were netted, placed in large, rubber boot-like containers, passed hand-over-hand down the embankment and lowered into the 60-degree water.

As the first one splashed down the crowd cheered and whooped.

MORE: Thermal hopscotch: How Columbia River salmon are adapting to climate change

The modest release—aimed at education and honoring a culture—is yet another step taken by the Upper Columbia River tribes toward sustainable reintroduction of salmon into a watershed long blocked by two of America’s largest dams—Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph.

There are seven dams on the Spokane River, all built between 1890 and 1922. None of those dams allow fish passage.

Sidestepping dams

While Idaho Congressman Mike Simpson’s proposal to breach four dams on the Lower Snake River has garnered lots of attention (and opposition), Upper Columbia River tribes have worked quietly to reintroduce salmon into the Upper Columbia River, a region rich with potential salmon habitat.

Line item: Volunteers hand down a rubber bladder holding salmon. Photo by Dan Pelle/The Spokesman-Review

Unlike advocates on the Snake River, tribal biologists and leaders are sidestepping the dam issue.

“Salmon and steelhead reintroduction into the historic habitats above Grand Coulee Dam will benefit the entire region, as our work so far indicates, successful reintroduction can occur without impacts to the current beneficiaries of Grand Coulee Dam: hydropower, flood control and irrigation,” said Carol Evans, Spokane Tribal chairwoman, in an email. “Truly a win-win.”

Instead, in 2015 the Upper Columbia River Tribes—which includes the Coeur d’Alene Tribe of Indians, Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation, Kalispel Tribe of Indians, Kootenai Tribe of Idaho and the Spokane Tribe of Indians—published a paper outlining a phased approach to the reintroduction of salmon.

In 2019, Phase 1 of that project ended. It determined, among other things, that the Upper Columbia River system is ripe with potential salmon habitat. That includes 711 miles of possible habitat for spring chinook and 1,610 miles for summer steelhead.

Of that spring chinook habitat, 80% was deemed to be highly productive while 53% of the steelhead habitat was judged to be highly productive.

Phase 2: 750 fish

Now the project is entering Phase 2, according to Conor Giorgi, the anadromous program manager for the Spokane Tribe of Indians.

Phase 2 will introduce tagged salmon into the system to test the habitat and survivability estimates developed in Phase 1.

Phase 2 will also focus on figuring out the best method for getting fish up and over Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams.

All of that, Giorgi said, should take at least five years.

MORE: As salmon cook in rivers, pressure on Biden mounts

A key step in the process will be the release of 750 yearling chinook in 2022.

Each will be tagged with a passive acoustic tracker that pings stationary receivers as the fish make their way downstream.

That data will allow the tribes to see how many fish survive going through, or over, each dam, as well as how many survive passage through the reservoirs.

The tribes also plan to release tens of thousands of tagged yearling chinook to assess survival through the main stem of the Columbia River downstream of Chief Joseph Dam.

World-class conditions

Phase 3 of the plan is to construct permanent passage facilities for fish coming up and down the river.

Those passages could be fish ladders, innovative technology like the Whoosh! “salmon cannon” (a flexible pneumatic tube that shunts fish over the dams, made famous by John Oliver in 2014), trucking fish or a combination of all three and more.

Into the wild: Volunteers help reintroduce salmon above Chief Joseph and Grand Coulee dams. Photo by Dan Pelle/The Spokesman-Review

“It’s an exciting project. It’s been rewarding to work on,” says Casey Baldwin, a research scientist for the Colville Tribe. “The long-term process of reintroducing salmon above Chief Joe and Grand Coulee is going to take a long time.”

While the tribes plod through the phases, they’ll also conduct several cultural and educational releases, like the August one in the Little Spokane River.

PODCAST: Bringing salmon back to the Upper Columbia River

These releases are aimed at educating the public, many of whom don’t realize that the Upper Columbia River system was once awash with salmon.

For example, one European explorer wrote that the salmon in the Little Spokane River were “thick as crickets” during an 1883 trip through the Northwest.

“A lot of folks don’t remember that this was a world-class salmon stream,” Giorgi says.

Submerged history

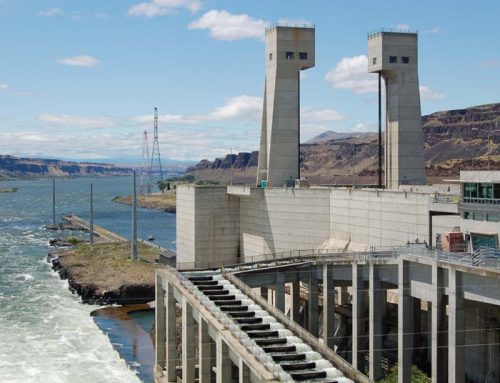

Since the Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph dams were built (without fish passage) in the 1930s and 1950s, respectively, salmon have been blocked from returning to spawning beds in the Upper Columbia River.

That’s not even accounting for the 272 other hydroelectric dams that pepper the Columbia River Basin.

But Grand Coulee and Chief Joseph are the biggest and when they were built they drastically changed the Columbia River Basin.

Without fish passages, salmon returning from the ocean were unable to reach spawning grounds. When the 500-foot-tall Grand Coulee Dam was finished, it raised the waters behind it 380 feet, flooding more than 20,000 acres of land nearly overnight.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]”To stand here today and know I’m making my ancestors proud, I’m overwhelmed.”[/perfectpullquote]

One hundred miles upstream from the dam, the town of Kettle Falls was submerged by the rising waters.

The area was called Shonitkwu in Salish—it meant “noisy water,” as the river used to drop more than 50 feet, tumbling over a series of massive quartzite blocks. That frothing, roaring water could be heard from miles around.

MORE: Breach on! Idaho Rep. Simpson calls for removal of Snake River dams

In the Spokane region, Kettle Falls was one of the prime fishing spots. Early written accounts recall a river so jammed with the fish that one couldn’t throw a stick without hitting a salmon.

Each year, at least 14 Native American tribes from throughout the region, gathered there to fish for salmon and trade news and goods.

Now, those falls are submerged under 100 feet or more of water. The town itself, relocated as the waters rose, is a blip on U.S. 395 with a name that makes no sense.

Redemption song

That history was front and center on the shores of the Little Spokane River during the August release.

“Salmon, for us, it’s kind of a spiritual experience,” said Monica Tonasket, a Spokane Tribal councilwoman. “Those salmon have a spirit.”

Historic flow: Isaac Tonasket sings a song from his ancestors upon the release of salmon into the Little Spokane River. Photo by Dan Pelle/The Spokesman-Review

Tonasket’s grandfather was forced from his home when Grand Coulee Dam was built, she said. He lived his entire adult life without salmon.

“For me to be able to stand here today and know that I’m making my grandparents, my ancestors proud, I’m overwhelmed,” she said. “I’m just overwhelmed.”

Eli Francovich is a journalist covering conservation and recreation. Based in eastern Washington he’s writing a book about the return of wolves to the western United States.