The following is an opinion piece. As such, the views and opinions expressed in the article are those of the author, and they do not necessarily reflect the views and opinions of Columbia Insight.

By Jean Sheppard. Jan. 24, 2019. I was born in Newark, New Jersey, an industrial town in the northern part of the state, where factories like Balbach Smelting & Refining Company, Engelhardt Industries, US Corrugated and Synthetic Plastics Company are located. In 1963, when I was six years old, we moved to Chatham, a suburb eight miles west of Newark. One of my strongest memories of growing up there were the “smog alerts” we got on TV whenever it was windless in the summer.

On hot summer days, we were frequently told that the air was “too polluted” for us to play outdoors. My brother and sister and I would fight over board games and get into trouble after being cooped up indoors during one of these “smog” events.

We would often drive back to Newark, or nearby Kearny, New Jersey to visit relatives and friends. On those drives I would see thick plumes of yellow smoke rising from the factories, and when you got close to them the odor was so horrendous and pungent that it would burn your nostrils. “Hold your noses,” my mom would say as we sped past on the New Jersey Turnpike.

Across the Hudson from Newark, the Manhattan skyline circa 1973. Photo courtesy of Wikimedia Commons.

A 1976 article from the Newark Star Ledger, entitled “Air Pollution Makes Life Miserable”, quotes Newark resident Karen D’Andrea, who complained: “The smoke coming out of Engelhardt smoke stacks has 3 distinct colors – yellow, gray and white. Every day when I come home from work, as soon as I get off the Delancy Street ramp, there’s a very strong odor. Even on clear days, you can see the smoke hanging over Engelhardt.”

Ms. D’Andrea reported that her son developed a serious recurring cough and her mother was informed by a doctor that her “swollen, teary and red eyes are definitely due to some form of pollution in the air.” Karen claimed that her neighbors had similar concerns, so she called the EPA three times and left messages for them. But her calls were never returned.

Another area resident noted that after complaints by neighbors, Engelhardt stopped polluting the air during daylight hours but resumed activities at night “when they thought no one would notice.” Engelhardt workers were also allegedly hospitalized after being overcome by fumes. Those that complained about conditions were said to be harassed on the job.

My uncle Carl worked at Engelhardt for over twenty years and died an untimely death from cancer, despite having no family history of the disease.

The recent assault by the Trump administration on environmental regulations got me thinking about the past, and it made me wonder about the history of air pollution regulations in the US. I decided to do some research on the history of the Clean Air Act to see if we are in danger of repeating our mistakes.

I learned that the health effects of air pollution were not widely considered, or even studied, until well after the Donora smog catastrophe. This incident, while not publicized, was the first time that air pollution resulted in massive illness and death in the United States.

On October 27, 1948 an air inversion trapped the emissions from two Pennsylvania factories, US Steel and American Wire. The pollutants in the air mixed with fog to form a thick, yellowish, acrid smog that hung over Donora for five days. The deadly smog continued until it rained on October 31, by which time 20 residents of Donora had died, and approximately one third to one half of the town’s population of 14,000 residents had fallen ill. Another 50 residents died of respiratory causes within a month after the incident.

It took another seven years after the Donora smog incident for federal legislation to be written, and in 1955 the Air Pollution Control Act became law. This federal statute authorized funds for air pollution research, but it would take more than fifteen years before the Environmental Protection Agency would be created to regulate air quality.

During the 1960’s, public pressure to clean up the environment started to develop and intensify. Finally, the Environmental Protection Agency was established by President Nixon and its first administrator, William Ruckelshaus, was sworn in on December 4, 1970.

Public desire for real action on environmental clean-up efforts continued to grow and was aided by the efforts of consumer advocates like Ralph Nader. The real catalyst for change was Senator Edmund Muskie of Maine. Muskie sensed that environmental issues might propel him to the White House, so he led the fight in the Senate for tough new laws. The resulting legislation was the Clean Air Act of 1970, which awarded the EPA direct responsibility for setting limits on air pollution and granted the agency the power to enforce those limits.

The Clean Air Act established a clear framework for the “attainment and maintenance of air quality standards.” It also “sets emission standards for motor vehicles and fuels, regulates hazardous air pollutants, protects stratospheric ozone and deals with acid rain.” As a result of the Clean Air Act, large industrial polluters had to install scrubbers in their factories and automobile manufacturers added catalytic converters to car engines.

The Act was amended in 1977 to give states more time to meet standards. Subsequent amendments to the Act were enacted in 1990 to target four areas: acid rain, urban air pollution, toxic air emissions and ozone depletion.

The Clean Air Act has been most effective in requiring that cars have catalytic converters and mandating yearly automobile inspection and maintenance. As a result, the Act and its amendments have dramatically reduced vehicle-related pollution. It has had a similarly positive effect on industrial pollution, with health benefits such as fewer premature deaths and asthma attacks. The EPA estimates that the Act prevented more than 160,000 early deaths, 130,000 heart attacks and millions of cases of respiratory illness.

The Clean Air Act was responsible for a significant reduction in air pollution in New Jersey. The state and the EPA track emissions using the National Emissions Inventory, and a 2011 study showed reductions in ozone levels, sulfur, formaldehyde, benzene and other pollutants from the 1950’s to 2010.

A view of West Delhi, India, where emissions grew by 6% in 2018. Photo by Jean-Etienne Minh-Duy Poirrier.

The story is not as hopeful at the national level, particularly when it comes to carbon dioxide. Between 2014 and 2016, global emissions of carbon dioxide were mostly flat, but in 2017 global emissions grew 1.6 percent and the rise in 2018 was more than 2.6 percent. This increase brings fossil fuel and industrial emissions “to a high of 37.1 billion tons of carbon dioxide per year.” Emissions by the United States grew 2.5 percent, while China’s emissions grew by 5% and India’s grew by 6%.

Against this background, it is shocking that the executive branch of the federal government is now rolling back regulations and completing its destruction of the Clean Air Act and other environmental laws.

The National Geographic Society has been quietly cataloging the pervasive and devastating changes in environmental regulations enacted or proposed by the Trump-era EPA. Ironically, the cover photograph for the 2017 issue of the National Geographic report is a 1963 picture of a factory in Newark, New Jersey belching smoke.

The magnitude of the changes proposed by the Trump administration are staggering in scope. Of course, pulling out of the Paris Climate Accord was Trump’s first and most dramatic action, but there are others that will impact air quality more directly and could bring us back to the days of foul air and ill health.

Last month the EPA repealed the Obama-era methane rules. This change would reduce requirements on oil and gas companies to monitor and mitigate releases of methane from wells and other operations. Methane is an extremely potent greenhouse gas, but of course the industry complained about the cost and record-keeping required by the rule. Clearly, the EPA was overly influenced by industry complaints, and the attorneys general in California and New Mexico immediately filed suit to challenge the new regulation.

Trump’s first EPA Director, Scott Pruitt, was forced to resign amid complaints of ethics violations, but his acting replacement, Andrew Wheeler, a former coal industry lobbyist, has vowed to continue the EPA’s assault on environmental regulations. “Wheeler has advanced the same destructive agenda as Pruitt, but without sideshow antics slowing him down,” Brett Hartl, government affairs director at the Center for Biological Diversity, said in a statement. “If he’s confirmed, Wheeler would surpass Pruitt as the most dangerous EPA administrator of all time. The Senate must not give him the chance.”

In August, the Trump EPA announced plans to nullify federal rules on coal power plants. Why? Because that was one of candidate Trump’s campaign promises: to weaken air pollution rules on coal-fired power plants. President Obama’s Clean Power Plan was designed to cut US emissions by 32 percent below 2005 levels by 2030. The Trump plan would cut emissions by about 1.5 percent.

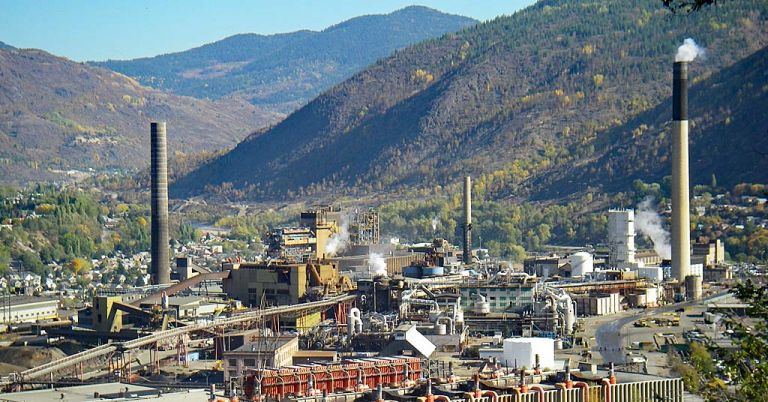

By rolling back Obama-era regulations on coal-fired power plants, the Trump administration is making it easier for facilities like the Sherco Generating Station in Minnesota to pollute. Photo by Tony Webster.

In January of 2018, the EPA loosened regulations on toxic air pollution. Environmental groups like the Natural Resources Defense Council rate this as among the most dangerous actions that the Trump EPA has taken against public health, and they are joining other groups to sue the EPA and block this policy change.

The Trump administration has also announced their plan to dismantle the Obama-era policy that would have increased vehicle mileage standards for cars made over the next decade. Mr. Trump’s alleged rationale is that people who own more efficient cars will drive more, putting them at risk for more accidents, so the EPA is claiming that they are relaxing emissions standards to “promote traffic safety.” This move sets the stage for a legal battle with more than a dozen states, led by California, that have passed their own higher fuel standards.

Just last month the Trump EPA announced that limiting mercury and other toxic emissions from coal and oil-fired power plants is “not cost-effective and should not be considered ‘appropriate and necessary.’“ The National Mining Association championed the announcement, “calling the mercury limits ‘punitive’ and ‘massively unbalanced.’” Scientists and physicians claim that mercury in the air poses health risks to unborn babies and young children, while also causing neurological disorders, heart and lung diseases and compromised immune systems. Court challenges to this rule change will surely come soon.

The courts have yet to issue opinions on any of the rules currently being challenged. However, Mr. Trump and his Republican allies in Congress have done an excellent job of packing the federal district courts, appellate courts and now the Supreme Court, with extremely conservative judges who will likely rule in favor of corporations and side with the government. Senate majority leader Mitch McConnell loves to brag that he is most proud of the fact that he successfully prevented President Obama from filling many federal court vacancies and one Supreme Court vacancy. This Machiavellian maneuver will insure that conservative courts will negatively impact environmental policies for decades to come.

The Trump administration’s rollback of environmental regulations to prop up polluting industries reminds me greatly of the decades-long battle waged by the tobacco industry to convince public health officials that smoking is perfectly safe and does not need to be regulated. As a result of a court order, the major tobacco companies are currently running ads on national TV admitting that smoking cigarettes is addictive and can cause cancer. I wonder how many needless deaths occurred while this controversy was making its way through the legal system. It is hard to believe that weakening air pollution standards won’t also cause senseless illness and death.

In December the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change determined that the world has just over ten years to prevent climate catastrophe. The Panel represented the work of nearly 100 scientists, who conducted over 6,000 studies. It went through an elaborate peer-review process with tens of thousands of comments. When Donald Trump was asked about it by a reporter he asked dismissively, “Who drew it?”

The dire warning in this study is terrifying. The world will need to take dramatic and unprecedented actions to cut carbon emissions at a rate fast enough to avoid complete disaster.

Yet, instead of embracing renewable energy sources and investing heavily in technology like electric cars, the Trump administration is rolling back every Obama-era regulation they can to placate their corporate sponsors and create jobs in states that voted overwhelmingly for Trump.

Twenty-one children are currently suing the Trump administration, claiming that they deserve clean air to breathe and clean water to drink, and that his policies are harming the environment. The department of justice has tried to have the suit dismissed several times without success. I hope these young people are successful in their quest, but I am not optimistic that the newly conservative-majority Supreme Court will rule in their favor.

It’s unfortunate that this administration cares so little about future generations. Their draconian actions may create jobs in the short-run and will surely increase the wealth of their big corporate donors but they will leave only a scorched earth for our children and grandchildren. As someone who remembers what it was like when the air was filthy and hard to breathe, I cannot imagine anything that would justify these short-sighted and negligent assaults on the Clean Air Act and other environmental regulations.

Jean Sheppard is an Adjunct Professor at Columbia Gorge Community College specializing in business management and the law. Her legal background includes private law practice in New Jersey as a municipal bond attorney and nearly a decade as a public finance investment banker for a major Wall Street investment firm. She is currently a volunteer attorney for Immigration Counseling Service and the ACLU of Oregon. Jean holds a JD from Seton Hall University School of Law and a BS with honors in Business Administration from the College of St. Elizabeth. She is a member of the New Jersey bar.

Jean Sheppard is an Adjunct Professor at Columbia Gorge Community College specializing in business management and the law. Her legal background includes private law practice in New Jersey as a municipal bond attorney and nearly a decade as a public finance investment banker for a major Wall Street investment firm. She is currently a volunteer attorney for Immigration Counseling Service and the ACLU of Oregon. Jean holds a JD from Seton Hall University School of Law and a BS with honors in Business Administration from the College of St. Elizabeth. She is a member of the New Jersey bar.