By Dac Collins. March 21, 2019. The City of Hood River aims to rezone Morrison Park in order to develop affordable housing on the property. Elected officials in favor of the development are calling it a compatible compromise between those in need of affordable housing and those in favor of preserving open space. Residents of Hood River who oppose the rezone are calling it a short-sighted land grab that could set a dangerous precedent for how parks are managed by the city.

This clash of opinions set the stage for the contentious and impassioned City Council meeting that took place on Monday, March 11.

A ponderosa pine stands watch over Morrison Park. Photo by Darryl Lloyd

During the four-hour public hearing, 26 citizens testified in opposition to the rezoning of Morrison Park, officially known as “Tax Lot 700”. One citizen testified in support of rezoning, along with two representatives from the Mid-Columbia Housing Authority, which currently has an executed option agreement with the city to purchase the property for $1.

“The only reason we’re giving this a passing thought, let alone struggling to figure out if we felt that there was a rational, reasonable pathway forward, is because of the importance of housing,” says Mayor Paul Blackburn.

He explains that Tax Lot 700 is “far and away the most feasible parcel for affordable housing” because it is centrally located, there are public services nearby and the city already owns it.

“The ODOT parcel, which is on Cascade above the skate park, is also an excellent location. It could work, but we would have to reimburse ODOT for relocating…and the early numbers I saw for something like that was 6 or 7 million dollars.”

“Okay. So, that would be a great spot,” he says. “If we had 7 million dollars.”

Blackburn was elected to his third term last November, and he has served as an elected official (previously as a city council member) since 2004. In that time, he explains, building affordable housing has become the city’s top priority.

That’s because in 2004, the number of people living within the city limits of Hood River hovered around 6,383. Today, that number is closer to 7,700.

This increase (of approximately 20 percent) correlates to the upsurge in median home prices over that same period of time. Jumping from $205,000 in 2004 to $459,100 in 2019, the median home price in Hood River has more than doubled over the past fifteen years.

And the rental market is even more prohibitive and unaccommodating. A report issued by ECONorthwest in September of 2015 found that “nearly one-third of Hood River’s households are unable to afford their current housing, with roughly 40 percent of renters unable to afford their housing.”

Predicting that the city’s population will continue to grow at a rate of approximately 2 percent a year, a key question from the 2015 study is “whether housing prices will continue to outpace income growth, [as] it seems likely that without public intervention, housing will become less affordable in Hood River.”

This is what a housing crisis looks like.

And it helps explain why Blackburn and other elected officials see affordable housing as their number-one priority when working to develop a sustainable future for the city.

Pitting housing against parks

Josh Sceva lives caddy-corner to the park. He has been involved with attempts to save Morrison Park since the city first tried rezoning the property in 2016. That was around the same time, Sceva says, that Hood River Parks and Rec. started cutting back on its maintenance of the park.

“Do you see a garbage can anywhere?” he asks while walking across a makeshift wooden bridge spanning the unnamed, perennial creek that winds through the property.

Photo by Dac Collins

“Now it’s pretty much up to the people, and when they see garbage they pick it up themselves,” Sceva says, now standing on the other side of creek.

Sceva sees the property’s potential as a westside hub for a citywide network of pedestrian trails and bike paths. Pointing to Jaymar Road, which passes underneath Interstate-84 and heads down toward the Columbia River, he says: “To me, it’s just seems so natural that you would have a path coming down from the westside through here, then on to the waterfront and downtown.”

For Sceva, the park is a valuable asset to the local community — a tranquil and wooded open space that provides solace for people, as well as habitat for wildlife and native trees, including Oregon white oaks, big leaf maples and ponderosa pines.

And for avid disc golfers like Devin Carroll, Morrison Park is literally the only game in town. In a place that’s become synonymous with extreme sports like kiteboarding, skiing and mountain biking, all of which require expensive gear, Carrol says disc golf is “the most accessible sport that I know of.”

“You don’t need thousands of dollars worth of gear…just a couple discs. It’s free to play the course and a lot of people don’t have to get in their car to drive here.”

Carroll tees off on the 9th hole. Photo by Dac Collins

Carroll plays disc golf year round. And as much as he appreciates the course, he says what sets Morrison Park apart from the other parks around town is that it’s an “urban forest”…an intact, natural woodland in the heart of Hood River.

He says its unfortunate that attempts to rezone Morrison Park have pitted housing advocates against park supporters because “we’re all huge advocates for affordable housing.”

“We’re all for it. We just believe that it should not come at the expense of our park. Or any park. Ever.”

As it turns out, there are quite a few people in Hood River who share those beliefs.

One of them is Susan Crowley, who says of the city’s continued attempts to rezone the parcel: [perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“They’re doing good work. Its just that they’re doing good work in the wrong place.”[/perfectpullquote]

She says her biggest concern is that the rezone could set a precedent for other parks, ostensibly making the city’s park system a land bank for potential development.

“There’s really no compromise for these kinds of resources. Having accessible places to connect with the natural world is so precious at this stage of our development, and when you lose parks they don’t come back.”

“Well, ultimately they come back,” she quips, “when we self-destruct as a species.”

These concerns led Crowley, an inactive member of the Oregon State Bar, to file an appeal with the Land Use Board of Appeals (LUBA) after the City Council first approved the rezone in May of 2017. LUBA upheld the Council’s decision in January of last year.

Crowley then took her case to the state Court of Appeals, which overturned LUBA’s ruling in September. The Court remanded the decision, finding the city’s reasons for rezoning “implausible” because they were in direct conflict with Goal 8, Policy 1 of the city’s Comprehensive Plan.

This forced the city to revisit the issue, and to serve as the impartial arbiter in deciding whether the applicant (the city itself) should be able to move forward with the rezone of Morrison Park.

Which brings us to the March 11 City Council Meeting.

Five minutes apiece

The underlying question of the public hearing that took place ten days ago was whether or not the city’s move to rezone Tax Lot 700 is in accordance with the stated intentions of Goal 8, Policy 1 of the city’s Comprehensive Plan:

“Goal 8 — Recreational Needs: To satisfy the recreational needs of the citizens of the community and visitors to the area.

Policy 1: Existing park sites will be protected from incompatible uses and future expansion alternatives at some sites will be developed.”

In other words, is developing affordable housing on an existing park a compatible use for that park?

Morrison Park in the spring. Photo by Darryl Lloyd

26 Hood River residents thought not, and they were each given five minutes to say their piece.

A number of those testimonies honed in on the key words of Goal 8, Policy 1.

Crowley focused on, among other things, the word “existing”. She pointed to the city’s Recreational Resource Inventory from 1983.

“I’ve attached the actual inventory of parks in Hood River and it has Morrison Park in it. You can see the acceptable uses, the expected uses, the anticipated uses for Morrison Park. And housing ain’t nowhere on there.”

“I support affordable housing,” Crowley said, “but you don’t put it on parks”

And resident Linda Maddox brought up the fact that “if you look at Policy 1, the meaning of ‘protect’ is to save from loss, destruction or injury.”

“If an existing park site is to be saved from loss, destruction or injury, as stated in the Comprehensive Plan,” Maddox continued, “then the construction of 67 housing units on top of Morrison Park is in no way a compatible use. Absolutely no way.”

Rio Bella Heights is an affordable housing development located in the Heights neighborhood of Hood River. Photo courtesy of Mid-Columbia Housing Authority

Scott Baker lives in Hood River but works in the Dalles. As the Director of the Northern Wasco County Parks and Recreation District, he explained, he spends a lot of time analyzing and implementing Comprehensive Plans.

“The Plan is a legal document and a statement of public policy, and as such it is a guiding document for all land use decisions” he noted.

Baker asserted that any attempt to modify the language in the Plan would undeniably set a precedent for how parks are managed in the future.

“It’s important that we follow the process and we don’t amend our Comprehensive Plan. Once a Plan is interpreted a certain way, it becomes the interpretation. It will become the interpretation for all of our parks, and this is not limited in scope to Morrison Park.”

Other testimonies focused on the property’s value as habitat and its importance as a wildlife corridor. One resident referred to Morrison Park as a “natural urban oasis”, and another held up her smartphone during testimony to show photos of the three hummingbirds she had seen in the park that afternoon.

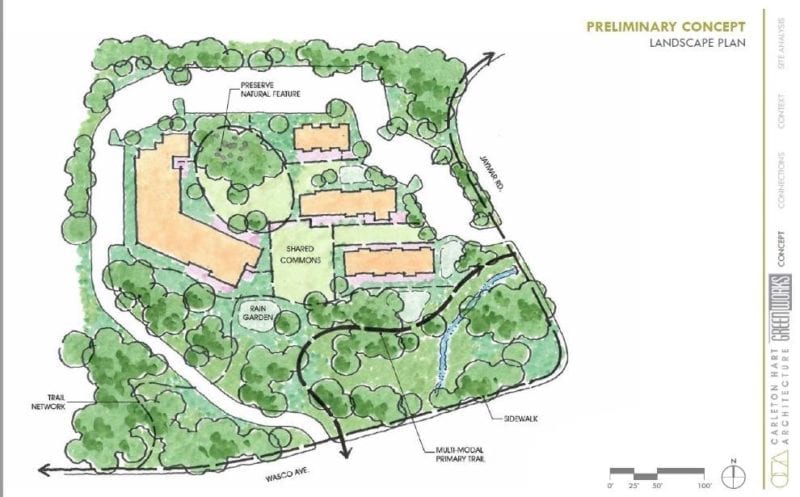

On the other side of the debate was Joel Madsen, Executive Director of the Mid-Columbia Housing Authority. During his testimony on March 11, Madsen argued that with proper planning and consideration for the natural elements of the parcel, the goals of development and preservation could be mutually inclusive.

“We see this development, while protecting park space, as also a viable option for us to achieve our mission in housing some our most vulnerable community members,” Madsen said.

In a separate conversation preceding the public hearing, Madsen discussed how the decision was reached to convert approximately half of Tax Lot 700 into a “mixed income development” and preserve the remaining acreage.

“We have been looking at this site pretty intensely for the last year and a half or so, and getting a better understanding of just exactly how much of the site can be preserved while also developing a nicely thought-out affordable housing development,” said Madsen.

A preliminary sketch of the proposed development. Courtesy of Mid-Columbia Housing Authority

“A few of the units would be affordable up to 80% area median income. A few units would be affordable up to 50% area median income, and a few at 30% area median income.”

“We want to champion that preservation of the park space,” he continued, but explained that roughly half of the parcel would have to be developed to make the project financially viable.

In the end, after nearly three hours of testimony and an hour of delegation, Council Member Erick Haynie moved to reject the rezone, arguing that the reason Goal 8, Policy 1 was established was “not to protect portions of an existing park, but the whole thing.”

Haynie’s motion did not get a second.

Council President Kate McBride — whose husband, Rich McBride, is on the board of the Mid-Columbia Housing Authority, as former council member Susan Johnson pointed out at the beginning of the hearing — then moved “to approve the rezone with no more than 55 percent (approximately 2.76 acres) of the tax lot to be developed as affordable housing; maximum 45 percent shall be set aside to incorporate park and recreational amenities and public facilities. The 55 percent that shall be developed as affordable housing shall be contiguous.”

Council Members Mark Zanmiller and Jessica Metta seconded the motion, while Tim Counihan and Erick Haynie voted against it. Mayor Paul Blackburn cast the tie-breaking vote (4-2) to rezone the 5.3 acre parcel from Open Space and Public Facilities (OS/PF) to Urban High Density Residential (R-3).

Morrison Park in the fall. Photo by Darryl Lloyd

“There’s a lot of people that weren’t in that room,” Blackburn said after the public hearing had concluded. “The testimonies, in my opinion, did not broadly represent the residents of Hood River, and it’s very important for us to keep that in mind. It’s very important for the elected officials to listen carefully to all the residents and to represent all the residents.”

“We try to receive all of it with the best grace we can and make the best decision we can.”

Crowley, however, confirmed that she will be appealing the City Council’s decision to LUBA.

“The city has proposed trying a rezone again knowing that it’s going to be appealed, and is choosing to waste public money and effort on litigation that will benefit only lawyers,” she said after the hearing.

She explained that, as before, “if LUBA supports this rezone attempt, it will then be appealed to the Oregon Court of Appeals.”

I am very disappointed to see the decision the City Council has come to. First there was discussion about affordable housing, now I see that changing. “A few of the units would be affordable up to 80% area median income. A few units would be affordable up to 50% area median income, and a few at 30% area median income.”

As the city grows there will be much more appreciation for green spaces, especially in the city. Morrison Park is a wonderful natural environment too small to be chopped up to include housing. What happened to swapping land for the ODOT lot. I seem to remember that was being discussed rather than ‘purchasing’ it for this exorbitant amount of money. $1 for Morrison Park – sounds absurd!

“There’s a lot of people that weren’t in that room” Well there is a great reason for that: The city led by Blackburn gave very little time and public notice of the meeting! Many of these meetings have been held last minute with the majority of the citizens left in the dark. If you want a more diverse group of attendees please plan the meetings further out and give proper notification to all the citizens. Better yet instead of last minute semi secret meetings how about we have a vote to see what percentage of residents want to Protect Our Parks! Parks are an integral part of human health in a growing concrete world. We cannot ever afford to lose a park. We do not need to chop off a foot to save a hand, we can have both. POP: Protect Our Parks #savemorrisonpark

Why not a long-term lease of the land to developers—like a100 year lease? That’s predicated on the idea that policymakers prioritize human values like affordable housing. I can’t stomach the fact that we’re raising taxes on citizens of Hood River, not realizing any ROI on Lot 700. How can we look each other on the eye, raise taxes, and squander opportunities for address human issues like affordable housing?

Yes we need affordable housing. But a PARK??? Good grief, are they out of their MINDS??? You have untold ACRES AND ACRES of land being used for strip malls and parking lots, things we need LESS OF if we are going to have ANY hope of reducing greenhouse gas emissions in the time required. Trees, on the other hand, ABSORB CO2. Are they NUTS?? Are they coddling developers, letting them get rich using other parcels for housing for the wealthy, then throwing up their hands and saying, “Oops! I guess there’s nothing left but the PARK. OH WELL.” This is insane, and I hope LUBA shuts this down, if it gets that far, and forces the city to use other land.

When the motion was made to deny the plan no one seconded it. Where were the voices of those who voted against it then? Seems like a well orchestrated plan to present an attitude of concern yet go forward with a land grab to me.

Here is a great video on the management of public lands

https://lawshelf.com/videocourses/entry/the-management-of-public-lands-and-wildlife-module-5-of-5?ac=mba9c2zb18