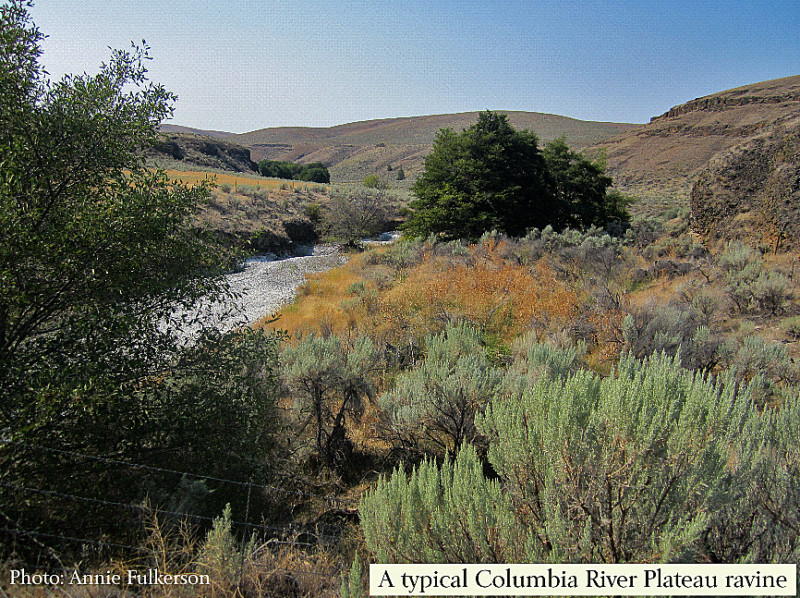

Just east of the dense forests and flowing rivers of the Cascades lies the Columbia River Plateau, a land of heat, dry grasses, rattlesnakes, and vultures. This essay explores the history of Eastern Oregon through the scope of a writers family and the story of the elusive Mary Sparks.

The glories of the Columbia River Plateau may escape the notice of travelers passing through the region. It’s probably impossible for most people to imagine wanting to move to some modest dale between two rolling ridges of black rock dusted with anemic topsoil and sagebrush. There’s almost always a stiff wind except sometimes down in the ravines, where the dominant sound in the summer is the placeless metallic drone of cicadas. There are grasshoppers and lizards, ticks and rattlesnakes.

However, some people are susceptible to the call of these austere uplands. Several different branches of my family chose to settle the Plateau, leaving the verdant, generous lands of Kentucky, Missouri and western Oregon to put down roots in Yakima, Boise, Blowout (a now-lost town in Idaho), Buhl (a tiny extant burg in Idaho), and Condon. What were they thinking?

I don’t know very much about my forebears as individuals. One reason is that my father’s family comprises a long string of taciturn, Asperger’s-spectrum people with ramrod straight spines and a grinding devotion to duty over just about any other pursuit. While I did hear stories of the various characters, it was difficult to get anyone in my father’s generation to provide much detail.

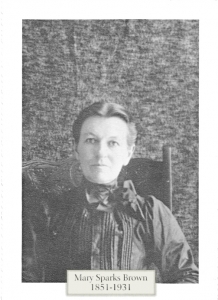

There was one woman on my father’s side whose mention inevitably brought a terse, yet laden with meaning, response. Her name was Mary Sparks. We had several Marys in our family so she had to be distinguished by her last name. During a conversation at our usual three-family Thanksgiving dinner, my father or his sister could just say ‘Mary Sparks’ and all the adults present would nod or sigh or purse their lips. It wasn’t that her story was tragic or scandalous, just that her name seemed perfused with all the information anybody should need to know about her.

Mary Sparks. Doesn’t she sound like a spunky nineteenth century heroine, a girl in a steampunk novel riding the struts of a dirigible during a battle, or Philip Pullman’s Sally Lockhart? A girl raising the alarm at the Triangle Shirtwaist Factory and getting all the other girls out by unlocking that fateful door? A frontier woman building a schoolhouse on the family ranch near Condon, so the local kids wouldn?t have to walk too far from home to learn to read? Yes! She does.

Even more romantically, the Sparks family has compiled an extensive and detailed genealogy. The first Sparks to settle in America was one William Sparks, who was born in the late 1600s in England. I suspect he may have emigrated owing to the exhausting and brutal religious wars of the Protestant Reformation. The name Sparks has been shortened from ‘Sparrowhawk.’ Wow! The nickname of the wizard Ged in Ursula LeGuin’s wonderful Earthsea novels. Romantic as hell, the name Sparks.

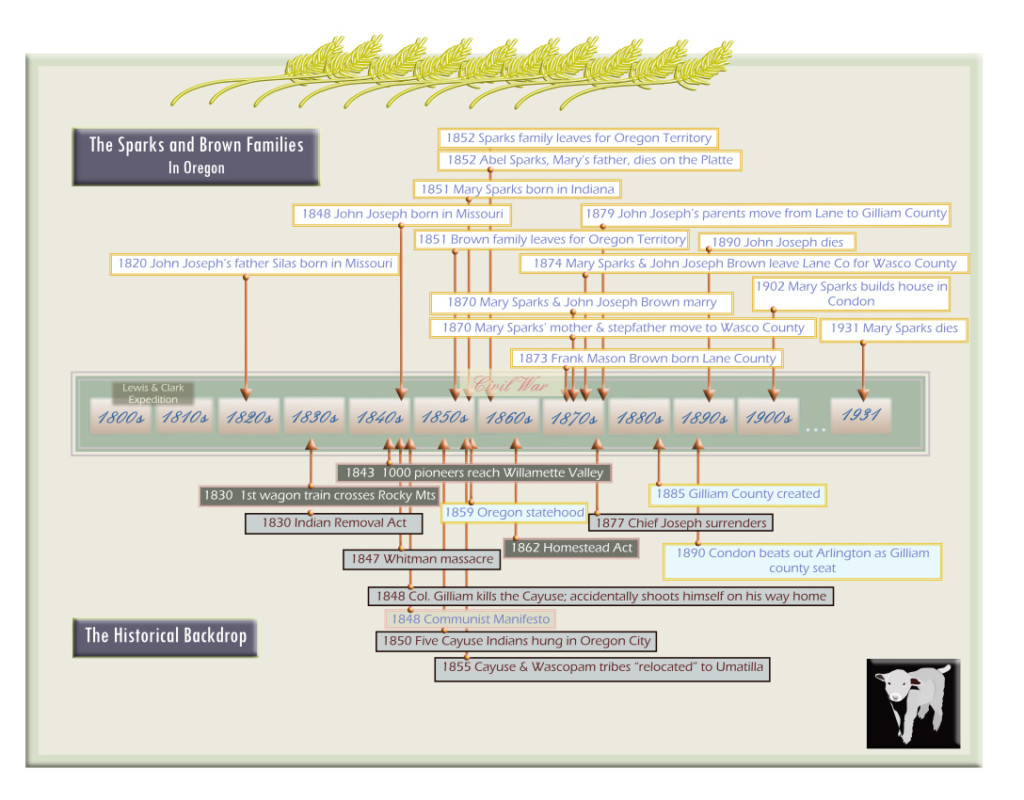

A Classic Pioneer Saga

So how did Mary Sparks get to Condon? In 1852 Mary’s young parents, along with other of her maternal relatives, set off on a wagon train to Oregon with their year-old toddler. Like many a pioneer, Mary’s father contracted cholera and died almost immediately along the Platte River somewhere in Nebraska. Mary and her mother persevered. When they reached The Dalles they had to leave much of their property in ‘storage,’ which they learned later meant they would never see their belongings again. I don’t know what they left behind, but if they were anything like other immigrants on the Oregon Trail, this probably included furniture and items–difficult to carry in the canoes they rode down the undammed Columbia River to its confluence with the Willamette. When the Sparks family group finally reached the Willamette Valley, they split up. The women settled in Albany for the winter. To earn money the men went to Puget Sound and fished. At the end of the season they reunited and moved to Lane County.

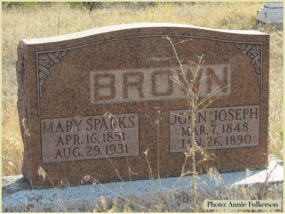

Sometime during Mary’s wonder years she met John Joseph Brown, whose family had arrived in Lane County by wagon train in 1851 when he was three. ‘Sparks’ may have flown; in any case Mary and John Joseph were married in 1870. She traded in her adventuresome name for an incredibly common one with a pedestrian meaning, thereafter remaining Mary Sparks only within the extended family.

Sometime during Mary’s wonder years she met John Joseph Brown, whose family had arrived in Lane County by wagon train in 1851 when he was three. ‘Sparks’ may have flown; in any case Mary and John Joseph were married in 1870. She traded in her adventuresome name for an incredibly common one with a pedestrian meaning, thereafter remaining Mary Sparks only within the extended family.

Mary and John Joseph stayed in the lush valley and forested Cascade foothills for four years, but packed up and moved to Gilliam County in 1874. (Actually, it wasn’t called Gilliam County then – it was still part of Wasco County until 1885). According to family legend, Mary Sparks drove the wagon herself – with her one-year-old and two-year-old sons, Ben and my grandfather Frank across the roadless expanse from Bend to what would become Condon.

In speculating as to why anybody would want to move from Lane County to Gilliam County, it had crossed my mind that Mary Sparks might have wanted to put some distance between her in-laws, or her parents, and herself. But she and John Joseph actually followed her mother, who had moved to the area with her second husband in 1870, and John Joseph’s parents followed the young couple in 1879. So either that wasn’t the motivation or the plan didn’t work.

I think the real reason was their collective clannish orneriness, or maybe the Willamette Valley was a little too thick with Methodists – and they probably succumbed to the lure of Columbia Plateau boosters. Here, is one of the finest examples of settler-attracting marketing:

A blessed land is that which suffers neither the extremes of winter’s cold nor summer heat. Such a land is found in Eastern Oregon. Winter is little more than a name in this favored section while the summer is free from sultry weather and the nights are always cool and refreshing.

The soil is a heavy loam, with just enough sand to make it warm and responsive. It is very fertile and the peculiarity of the soil is the fact that the longer it is cultivated the better crops it raises. The land is free from stone or gravel and the soil on top of the highest hills is deep and fully as productive as in the valleys. Good water is found in plenty in all parts of the county. A mild climate, plenty of good pasturage, pure water and good shipping facilities combine to make it an ideal stock country.

The atmosphere is pure and bracing with plenty of bright sunshine and no malaria. The healthfulness of Gilliam County is unexcelled.

-A. Shaver in collaboration with Arthur P. Rose, R.F. Steele, and A.F. Adams, compilers. An Illustrated History of Central Oregon: embracing Wasco, Sherman, Gilliam, Wheeler, Crook, Lake, and Klamath counties, state of Oregon. Spokane, Wash.: Western Historical Publishing Co., 1905.

[Emphasis added.]Anybody who’s so much as picnicked in that part of Oregon knows it’s sheer fantasy, except for the pure water, rich soil and lack of malaria (which was endemic in the Willamette Valley until after World War Two). But this kind of blather was used in many places around the West at the time.

The family established a sheep operation and eventually owned 1,200 acres. Mary’s oldest son, Ben, died at age eleven from an unknown cause, leaving my grandfather as the eldest. Mary bore five more children at the Gilliam County homestead. They seemed to have achieved the dream when John Joseph died leaving Mary a widow at thirty-nine with her five surviving sons and one daughter ranging in age from three to seventeen. Drawing on her reserve of spunk, she changed the family business name to Mary Brown & Sons and kept going with the sheep as long as she could. I have yet to discover how long the family business endured. The sheep business in Eastern Oregon was focused on the wool market in Shaniko at the turn of the 20th century, but the town was elbowed out by Bend and Madras when the rail line was built from there to the Gorge.

I know that my grandfather visited Boise periodically he may have also been marketing hogs and hay, because he met Emma Campbell, my grandmother, in Boise very much a woman in the same mold as Mary Sparks. By 1908 Frank and Emma were married and living outside Boise. We have several letters from Frank to Mary Sparks, some written on the backs of the racing forms from the 1911 Idaho Inter-Mountain fair at Boise indicating he still had some sheep in Idaho. But back in Condon, after the railroad was finished along the Columbia River most of the land was turned over to wheat.

In 1927, on Mary’s 76th birthday, her family held a surprise party in Condon covered by a reporter from the Condon Globe Times. The reporter wrote:

Mrs. Brown has lived on Rock Creek a total of 35 years, alternating in the last number of years between there and her home in Condon which was built in 1902. Although the city called, Mrs. Brown would not answer and stuck tightly to the farm always saying that the city was no place for her with five sons.

One of our most poignant family documents is a letter from my grandfather Frank to his mother in January 1928. By then Frank and Emma were farming near Boise. He reports to his mother that his crops, mainly hay, had fetched good prices. “One more year as good and things will begin to look normal,” he wrote.

Farmers must, of necessity, be optimistic about the future, but this accumulating prosperity wasn’t to last. Just when Frank and Emma finally built their dream house in Caldwell, the market crashed in October 1929. They’d put their money in six different banks to hedge against economic stresses, but every single bank failed. Emma responded by developing a fundamentalist vision of the looming apocalypse and forcing vagrants who came to her door to hear a Bible reading before she fed them.

Nor could it have been easy on Mary Sparks. She died in 1931 just as the Great Depression was ballooning into a long-term disaster.

Condon declined as well. The county had reached its peak population (so far) of 3,960 in about 1921. Today about 2,000 people live in Gilliam County. The main crop seems to be wind towers. There is still plenty of dryland wheat but few sheep. Condon has small-Western-town charm; you can get an ice cream cone and eat it on a shaded bench in front of the general store while watching the pickup trucks roll by. The Hotel Condon across the street has been refurbished in authentic retro style.

One of the enduring marks Mary Sparks and the Browns left on the Gilliam County landscape now sits on the grounds of the Gilliam County Historical Museum in Condon. In line with their civic ambitions, the Gilliam County pioneers had resolved to build schoolhouses in locations ensuring that no kid would have to make more than a seven-mile one-way trip to school each day on foot or horseback. The Brown family built one that fell down in a windstorm; their second attempt is open to tourists at the Museum, furnished with all manner of period textbooks, lunchpails, helpful posters, heavily initialed desks, and so on. There’s a fantastic bell that visitors are allowed to ring.

My family was so tight-lipped about our past that I didn’t even realize Mary Sparks was my great-grandmother for many years. Sometime in my young adulthood my dad let slip that we had forebears buried around Condon somewhere. He had never bothered to mention it before or even visit the place himself. It took me and my sister about three decades of desultory research to finally locate and visit the place. It is utterly typical of the area and utterly bewitching to those of us with the gene for sagebrush and lizard appreciation.

Retroactive Regret

Even as my breast swells with pride in my brave, hardworking pioneer ancestors, I know the story looks very different from other angles. Particularly the Native American ones. Condon was built on the site of a spring used by generations of Indians following their food sources through the seasons. White settlers’ treatment of the original residents of the Columbia Plateau was as shameful as anywhere else in North America. As far as I know my family never actually pulled the trigger or handed out smallpox blankets, but they certainly took advantage of Colonel Gilliam’s revenge on the Cayuse for the Whitman Massacre. The timeline graphic clearly shows them moving into the area right after the Indians were moved out. I’m sure they approved fully of the forced ‘relocation’ of the various indigenous tribes to the Umatilla, Yakama and Warm Springs reservations.

And of course there is no better way to destroy native rangeland than to scatter sheep all over it.

So the Sparkses and Browns exemplified the eternal paradox of settlers: narcissistic entitlement blinds us to our destructiveness until it’s too late – until after we’ve fallen in love with what we have vanquished. We dismantle the paradises we occupy. I hope I can retain the honesty, the courage and the commitment of my forebears and use these gifts in ways that mitigate the damage they inflicted on both the original residents and the land. Given the challenges facing all of us – especially climate change and the legacy of unregulated chemicals and nuclear waste – the way we did things over the last two centuries will not get us through the next two.

Out on the Columbia uplands, the wind never stops, the grasses rustle, the sky is huge and empty. I have an impulse to put a tiny house in the flat part near the creek. Except that the property belongs to somebody else now.

Valerie,

This is a beautiful story from your past. I like the tie to today and it does make one think of whether we learn any lessons. I think it was neat that you included the headstone. I will check out the school when we are in Condon.