Yakama Nation leaders continue to oppose pumped hydropower storage project in Klickitat County

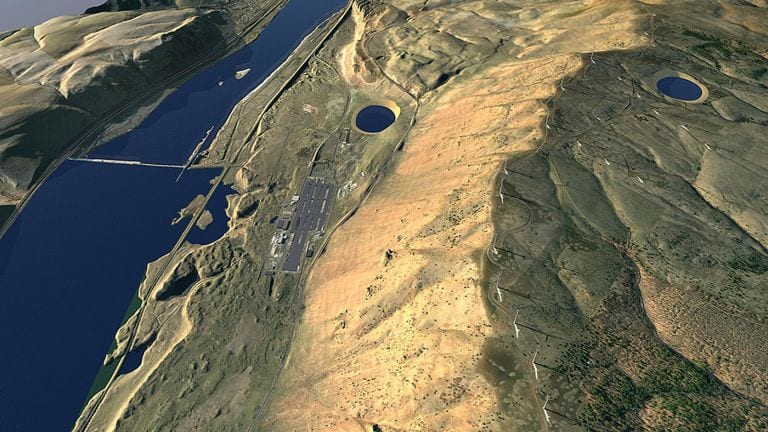

Powering up: This rendering depicts the proposed Goldendale Energy Storage Project, south of Goldendale, Wash., near the John Day Dam (lower left) and a defunct aluminum smelter (lower center). Illustration: Rye Development

By Kendra Chamberlain. January 28, 2026. The hotly contested Goldendale Energy Storage Project, located near Goldendale, Wash., has been awarded a key 40-year construction and operations license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC). The decision comes after a five-year application process.

Developers still have regulatory hurdles to pass before the controversial pumped-hydropower storage project is a done deal. These include submission of construction plans and safety and dam-engineering documents, and obtaining state, federal and local permits related to wetlands, storm water and land disturbance. Approval must also be secured from the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for work related to federal waterways.

But FERC approval is a major step forward.

Florida-based Rye Development, the firm behind the pumped hydropower storage project, expressed excitement about moving closer to the finish line.

“This is a landmark moment for the Pacific Northwest,” Erik Steimle, Rye Development director of development, said in a statement.

Rye Development is partnering with Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners to construct the facility.

The FERC decision has outraged opponents of the project.

Leaders of the Yakama Nation, who have consistently voiced opposition to the location of the project, are angry that their objections to development of a culturally important plot of land has seemingly fallen on deaf ears.

“Federal agencies are rewarding bad actors who have spent years finding loopholes to target a new wave of industrial development on top of indigenous sites that have religious and legendary significance to the Yakama People and many others who don’t have political connections or deep pockets” said Yakama Tribal Council Chairman Gerald Lewis in a statement.

“Elected Yakama leadership have met with tribal leaders in Oregon who face similar challenges—regulators in D.C. that do not hold private developers accountable to the laws that are meant to protect the environment, our foods or important historical sites, and instead issue incomplete licenses with only an afterthought of losses and destruction to Yakama resources,” said Lewis.

Energy Demands vs. Tribal Heritage

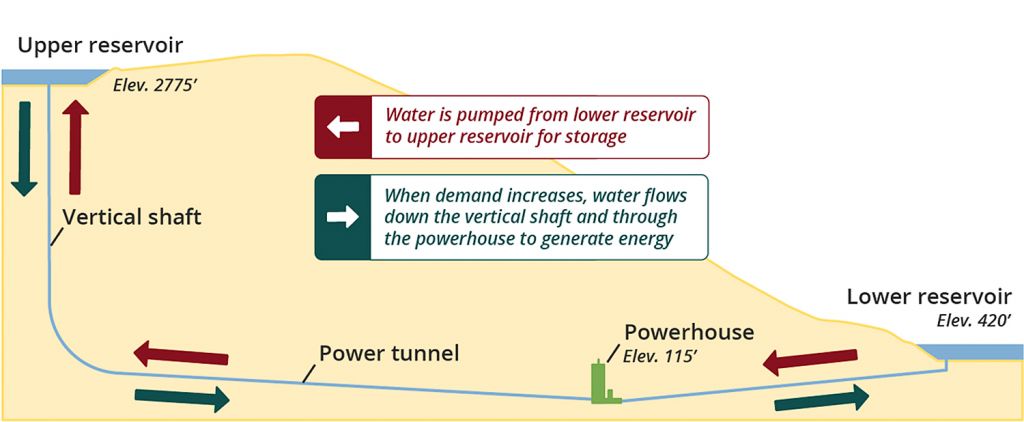

Closed-loop, pumped-hydro systems, such as the one planned for Goldendale, rely on pumping water uphill from a lower reservoir to an upper reservoir via a subterranean pipe when the price of electricity is low, and moving the same water back down the pipe to spin a turbine when the price of energy is high.

If built, the Goldendale facility will span the site of a defunct Columbia Gorge aluminum smelter and the Tuolmne Wind Project.

One storage pond will be located at the top of a ridge that overlooks the Columbia River.

The other storage pond will be downhill, adjacent to the old smelter.

Water will move back and forth between the ponds to store energy and, when needed, feed that energy back to the grid.

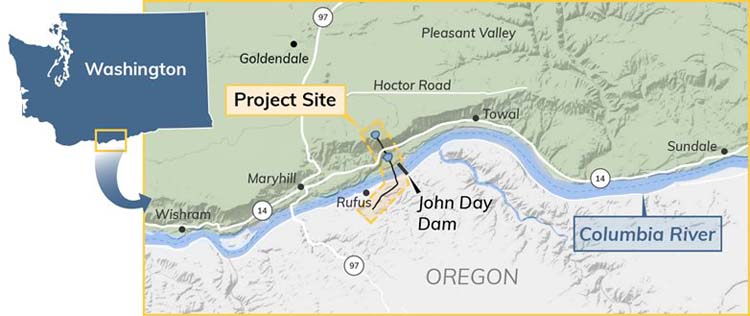

Goldendale Energy Storage Project location. Map: Wash. DOE

The project will include remediation of the site of the old aluminum smelter, an estimated $15 million cleanup taken on by Rye Development and overseen by the Washington Department of Ecology.

Rye Development says the facility will store electricity for up to 12 hours and generate 1,200 megawatts of on-demand electricity.

According to the Seattle Times and other sources, rapid data center expansion is a major driver of increased electricity demand in Washington.

Rye says the facility “is expected to create more than 3,000 family-wage jobs during its four- to five-year construction period, as well as dozens of permanent jobs.”

Proponents call the project a win-win, and a necessary step toward helping the region achieve its zero-carbon emissions goals.

“This is a project that’s been looked at by the Goldendale community since the 1990s as part of their overall economic development plan for renewable electricity, primarily wind, then solar and pump storage, all part of the energy overlay zone,” Steimle told Columbia Insight.

But some green energy advocates aren’t willing to look past the Yakama Nation’s opposition.

“It can’t be considered green energy if it’s impacting and obliterating cultural resources,” Simone Anter, senior staff attorney at Columbia Riverkeeper, told Columbia Insight. “Cultural and religious resources are part of the environmental review. You see them in NEPA [National Environmental Policy Act] reviews and SEPA [State Environmental Policy Act] reviews. And so the destruction of them can’t just be sidelined as not environmental issues.”

How the proposed pumped-hydro project near Goldendale, Wash., will work. Image: Wash. DOE

Columbia Riverkeeper is standing with the Yakama Nation, but also challenging parts of the state’s Clean Water Act certification for the project.

Rye Development says it will work with Yakama leadership.

“Now that we have the license, it’s super important for us to continue to work with the affected Tribes on the final historic properties management plan for the project that does ensure protection of cultural resources, but also access to the site as we move through construction and into operation,” said Steimle.

If the company builds the facility, an important piece of Yakama heritage will be lost.

“They know it’s wrong,” Lewis said in his statement. “If a small Christian shrine sat on this site, the decision-makers would understand what ‘sacred’ means. During his last days in office, Governor Inslee encouraged FERC to consider damage costs of $25 million but developers rejected all specific commitments and hope to keep building the energy grid on still more sacrifices to the Yakama way of life.”