More snow on Mt. Hood means more water for local orchardists. Photo courtesy of USFS.

By Dac Collins. March 29, 2018. Snow. It is nature’s most elegant way of storing water. By accumulating at higher elevations during the cold winter months and then flowing down streams as meltwater during the warmer, sunnier months, mountain snowpack slakes the thirst of parched valleys throughout the Pacific Northwest.

And in the time since European immigrants settled these valleys in the mid-19th century, we have grown accustomed to, even dependent on, this natural cycle of accumulation and ablation. We’ve built vast irrigation networks and storage reservoirs that allow farmers to continue watering their fields even during the driest spells of summer.

But what happens if it stops snowing?

As the Earth continues to spin and our species advances further into the Anthropocene, water managers in the West are asking themselves this very question.

A study published by the Oregon Climate Change Research Institute (OCCRI) earlier this month takes a good, hard look at snowpack levels in the West today. In the study, researchers examined data gathered over a 100-year period (1916-2017) at 1,766 snow monitoring (SNOTEL) sites across the region. And looking specifically at the measurements taken on April 1 (usually the highpoint for snowpack in most areas) they noticed an obvious and disconcerting downward trend.

The study, entitled ‘Dramatic declines in snowpack in the western US’, reveals that over 90% of the snow monitoring sites throughout the region show declines in snowpack. Philip Mote, the study’s lead author, writes that “declining trends are observed across all months, states and climates, but are largest in spring, in the Pacific states, and in locations with mild winter climate.”

“The decline in average April 1 snow water equivalent since mid-century,” Mote continues, “is roughly 15-30% percent, comparable in volume to the West’s largest man-made reservoir, Lake Mead.”

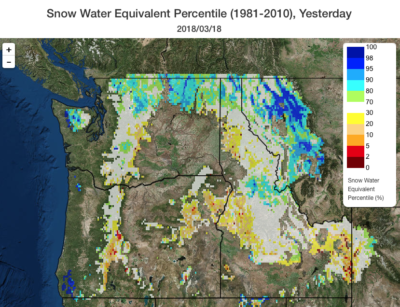

This map of the Pacific Northwest takes the amount of snow water equivalent (the amount of liquid water you would get if you melted the snow) as of March 18 and compares it to the average amounts measured on that same date from 1981-2010.

Of course there are always exceptions to the rule, as evidenced by the current above-average snowpack levels in parts of the Northern Rockies, but these small spikes have a negligible effect on the overall warming trends that define most mountain ranges in the American West. Also called ‘snow droughts’, these trends are perhaps most pronounced in the wetter and milder Cascade Range, where the amount of winter precipitation has more or less stayed the same but temperatures have warmed to the extent that what used to fall as snow now tends to hit the ground as rain.

“The year 2015 was a really good illustration of that,” Mote says. “Oregon had close to average winter precipitation, but it was about five degrees warmer than average, leading to record low snowpack at most sites in Oregon.” Hood River County declared a drought emergency that same year.

2015 was also the year that the US Bureau of Reclamation released a Hood River Basin study. The study found that “there is already a lack of adequate streamflow in the basin during the summer months to meet the competing demands for water,” and that “this imbalance is expected to be exacerbated by climate change.”

With findings like these, climate researchers like Mote find it difficult to maintain a certain level of optimism.

“It’s kind of depressing,” Mote says ruefully. “I hate to think what the story will be ten years from now.”

Until then, the only thing we can do is adapt. This means adjusting the ways we think about and manage our water, especially in terms of irrigated agriculture, which uses an estimated 85 percent of the water diverted for out-of-stream use in Oregon.

Farmers Irrigation District (FID) supplies irrigable water to growers on the westside of the Hood River Valley. And as manager of the district, Les Perkins is fully aware that the natural cycles we have built our infrastructure around are changing drastically. So he’s changing our infrastructure.

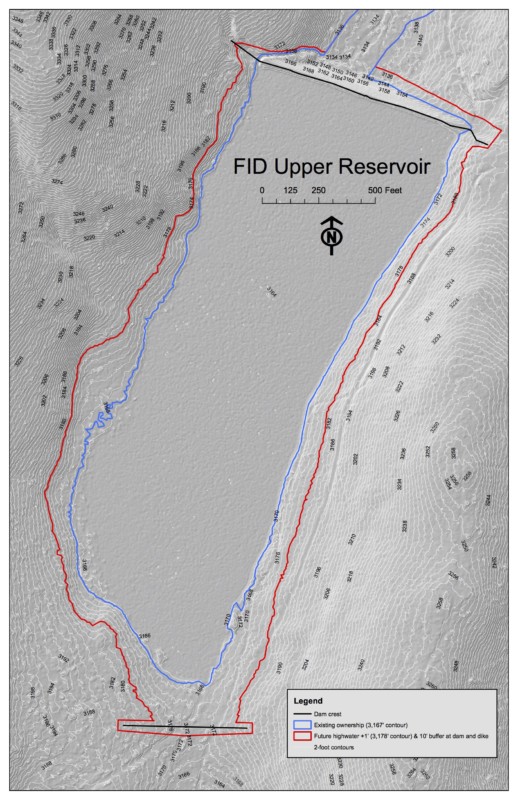

As part of a significant expansion project funded with grants from the Oregon Water Resources Department’s Water Supply Development Account and the DEQ’s Clean Water State Revolving Loan Fund, FID has made plans to raise the level of Kingsley Reservoir by 11 feet, effectively doubling its storage capacity.

The Kingsley Reservoir Rehabilitation Project involves the construction of another, larger dam behind the one currently in place, as well as a new earthen dam on the upstream side of the reservoir. This structure—also called a ‘saddle dam’ — will keep the newly raised reservoir from spilling over its banks. Last fall, FID completed the first phase of dam construction, which involved removing the 80-year old steel outlet pipe at the bottom of the dam and replacing it with a stronger, more efficient pipe made of high-density polyethylene. The district also updated 2.2 miles of the Lowline pipe, which feeds the middle part of the district.

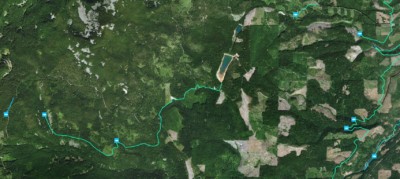

Aerial imagery of Kingsley Reservoir highlights the district’s network of pipes, including the Stanley Smith pipe (bottom left) that feeds the reservoir. Photo courtesy of FID.

With the new pipes in place, FID partnered with local contractor Crestline in order to construct the new dam this summer. However, delays in the permitting process have pushed that project back until the summer of 2019.

Perkins, a Hood River local who has served as County Commissioner for the past seventeen years, sees the Kingsley project as just one piece of the water management puzzle. He says updates to the district’s irrigation infrastructure have been underway for well over a decade.

By piping over 70 miles of open irrigation ditches, establishing a sprinkler exchange program with local farmers to replace outdated impact sprinklers with micro-sprinklers, and by building a centralized water pumping and filtration system, FID has vastly increased its conservation potential. “We can serve our farmers with half as much water as we did 30 years ago,” Perkins says proudly.

“And then our district produces about 25 million kilowatt hours a year through our two facilities,” Perkins adds. “We recently did our carbon footprint analysis, and we have enough renewable energy credits offsetting our vehicle usage so that we’re actually carbon neutral.”

Perkins’ focus on renewable energy speaks volumes to how he perceives his role as a water manager. He might represent the growers in an official capacity, but he sees other water users in the valley as equally important— especially the fish that require enough water left in their native streams.

And by utilizing more stored water for irrigation purposes, Perkins’ district will be able to get away with pulling less water out of streams like Green Point and Dead Point Creeks.

“There’s a big fish component here,” he says. “We spent quite a bit of time with ODFW and Confederate Tribes of Warm Springs going over what they wanted to see, and they both wrote letters of support for the project.”

This drawing of Kingsley Reservoir shows the current (blue) and future (red) high water lines. Photo courtesy of FID.

Referring to the project’s inception, Perkins explains: “What we looked at was: what is our conservation potential and what would stream flows look like if we added some additional storage. If we don’t do anything, stream flows are obviously heavily impacted—and they are already incredibly low. If we focus on conservation alone, that brought [stream flows] pretty close to where they are now. So we looked at storing some of the increased winter flows and using that rather than stream flow later in the year.”

“With that,” Perkins continues, “we’re actually able to come up above where our stream flows are now, even with population increase and climate change.”

Although construction of the new dams will not begin until next summer, the district has plenty of work to do in the meantime, including developing a rock source for the project and logging the area that will be inundated—an area that incorporates the campground currently located on the eastern bank of the reservoir.

Plans for the new and improved campground are already in place, however, and FID is working hand in hand with Hood River County Forestry to try and open the area to the public by the summer of 2020. The plans feature a new boat ramp, twice as many camp sites, a larger day-use area and five times as many bathrooms.

The campground renovation project illustrates how the district’s adaptive approach to water management can benefit community residents while also meeting the needs of the fish and farmers that play a vital role in this valley’s future.

“Our growers have gotten by, even in drought years,” Perkins says. “But it’s a little unnerving just seeing what’s happening with drought cycles becoming more intense. This [project] gives our growers some certainty that they will have the water they need in the future.”

I’d like to thank Mr. Perkins for his proactive management of water resources for Hood River County agricultural use. The expansion of Kingsley reservoir will mean less stress on the future of West Side orchards and farms.