Digging deep: Cryptocurrency “mining” is reshaping energy consumption in the Mid-Columbia Region. Image by Marco Verch Professional Photographer

By Jordan Rane. June 3, 2021. “It was a real Wild West-type situation here for awhile,” says Ron Cridlebaugh, Chelan Douglas Regional Port Authority’s director of economic and business development. “A lot of people thought, ‘Wow, here’s an easy place to make a buck with all of this cheap, renewable energy.’ And many of them came flocking in without any real business plan or clue.”

Cridlebaugh is based in East Wenatchee in Central Washington, home to the first U.S. highway bridge built over the Columbia River and enough area hydroelectric dams to garner an old regional nickname: The Buckle of the Power Belt. Back in the day, Cridlebaugh would receive what he calls “mining boom fever” inquiries from all over the world.

“Someone would call up and say, ‘I need 150 megawatts.’ And we’d say, well you can’t have it because our dams don’t even produce that much power beyond what we need for our community. Then,” he laughs, “they’d ask—‘Can we buy the dam?’”

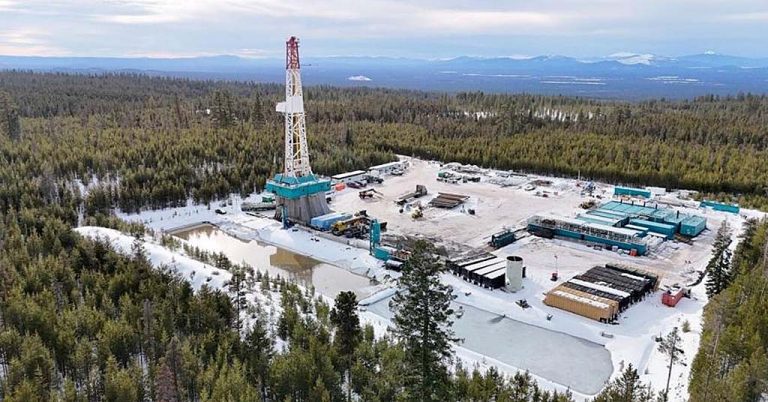

MORE: Developers back off controversial fracked gas power plant in Oregon

Like most booms, an inevitable bust period followed and the crowd of frenzied prospectors gradually dispersed.

“Nowadays there’s really just a few major players in Douglas and Chelan counties who draw more megawatts than, say, what an apple processing facility here would use at full tilt,” says Cridlebaugh. “I’d say the mining industry in the mid-Columbia has entered what appears to be a more mature phase.”

Wait a sec. Exactly which mining industry and which “boom” are we talking about here?

Bitcoin boom

First, a quick clarification of “mining.”

When Cridlebaugh refers to the “Wild West” days of prospecting, he’s talking about the cryptocurrency mining boom that kicked off in Central Washington a little less than five years ago.

It wasn’t about burrowing for gold nuggets. It was a pitched battle for blockchain in the virtual field of cryptocurrency mining.

Taking it to the banks: Bitcoin mining operation, location undisclosed. Photo by Marko Ahtisaari/Creative Commons

The computer-driven method of processing alternative money transactions of Bitcoin and other digital cryptocurrencies has become one of the biggest industries this area has seen since apple seeds were planted and Alcoa aluminum plants were shuttered.

It’s an industry that didn’t exist in any shape or form before 2009 when the first batch of 50 Bitcoins (aka the Genesis Block) was “mined” on a personal computer by a mysterious person or group of people named Satoshi Nakamoto.

The fringe economic maneuver would lay the foundation of blockchain, a digital public ledger of encrypted, borderless alt-financial holdings. From this creation grew a symbiotic industry of cryptocurrency “miners” competing to computationally solve complex problems in order to validate crypto-transactions in exchange for commissions on transactions of Bitcoins and other cryptocurrencies.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“Bitcoin’s bull run is putting public utility districts in Central Washington on high alert.” —Bitcoin.com[/perfectpullquote]

The whole brain-bending business, you’ve likely heard, has managed to inspire global cryptomania.

According to the latest Investopia tally, there are now over 4,000 cryptocurrencies. The value of a single Bitcoin, the benchmark, which is now accepted by several major corporations, indecipherably soared to nearly $65,000 in April (10 years ago it was valued at a dollar) before plummeting to half that value in May. At publication time, it had yo-yo’d back up to $38,548.

For all of Bitcoin’s volatile market mystique, Warren Buffett rates its intrinsic value—or that of any other cryptocurrency—at a steady zero.

Massive suck

Is this all starting to make perfect cryptic sense? If not, don’t worry. You’re not the only one who doesn’t grasp the concept.

Gates: Malaria meds over Bitcoin. Photo Moritz Hager/World Economic Forum

“I’ve read articles about cryptocurrency, I’ve had it explained to me and I still don’t get it, and neither do you or does anyone else,” quipped HBO’s Real Time host Bill Maher in a recent crypto rant. Maher’s screed is head-nodding funny—until he gets to the real point, which is the environmental elephant in the room: cryptomining’s massive energy drain and its associated contribution to climate change.

MORE: Opinion: Storage is a critical piece of our clean energy future

Making Bitcoin from cryptocurrency mining—or, as Maher puts it, “guessing numbers to win imaginary prizes”—requires inconceivable quantities of round-the-clock, sky-high computing power. According to Bill Gates, mining for cryptocurrencies “uses more energy per transaction than any other method known to mankind.” He’s said he’d rather invest in malaria and measles vaccines than Bitcoin.

Reminiscent of an old Ripley’s Believe It or Not! nugget, the University of Cambridge estimates that in its entirety Bitcoin now accounts for 0.54% of all global electricity consumption. [An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated this figure to be “roughly half” of the world’s electricity consumption. —Editor]

According to a recent study published in the journal Nature Climate Change, Bitcoin alone may produce enough carbon dioxide emissions from its growing global energy demands and fossil fuel usage to raise the planet’s temperature 2°C by 2033.

Central Washington: Megawatt magnet

Back in Central Washington’s Mid-Columbia Basin—a region famous for apple orchards, beautiful state parks and hydroelectric production—cryptocurrency miners remain attached to plentiful power and some of the lowest energy rates in the country, as well as cool air (giant banks of crypto-computers produce a ton of heat) and commercial rents that are a fraction of those 150 miles west.

Utility player: Ron Cridlebaugh. Courtesy Chelan Douglas Regional Port Authority

Due to marginally higher utility rates than Washington, the cryptocurrency mining boom has largely bypassed Oregon. In Idaho—which has been identified by at least one consumer group as the second-cheapest state for cryptocurrency mining—investment groups are actively promoting the state to prospective miners.

But Central Washington remains the center of Pacific Northwest activity and the industry’s rapid rise has sparked reaction in the region’s comparatively small communities.

“My perception is that the community at large probably doesn’t really understand crypto and especially blockchain technology, so I don’t think they necessarily have a favorable opinion of these mining operations,” says Cridlebaugh. “Part of that is likely shaped by those early days when people were coming in and they were so desperate to get into this business that they would rent a house—not even live in it—and stick in as many monitors as they could with the window open.

“In residential communities, it was forcing the PUD (Public Utility District) to have to deal with this and start cracking down on illegal mining operations. So those early times, I think, really tainted these communities’ views of mining and the ongoing potential value of blockchain and cryptocurrencies as an international exchange.”

Public utility issues

Local utility concerns about cryptominers flared earlier this year with the unexpected surge in cryptocurrency values.

“Bitcoin’s bull run is putting the public utility districts in Central Washington on high alert, monitoring for suspiciously high power bills,” wrote Bitcoin.com, summarizing a January Seattle Times report. “PUD officials claim cryptominers from China have come to the region to take advantage of its low hydroelectricity prices.”

Money machine: Cryptocurrency miners don’t need to be told Rocky Reach Dam near Wenatchee has a generator nameplate capacity of 1,300 megawatts. Photo courtesy Chelan County Public Utility District

Dealing with crypto-houses, soaring energy demands and the risks of the industry’s inherent transiency, Chelan, Douglas and Grant County PUDs have instituted adjusted rate schedules for local cryptomining businesses. While those prices still remain relatively low by national standards, energy consumption levels appear to have stabilized accordingly.

“County-wide energy use from cryptomining customers is now about 2-4 average megawatts—well below our 5% threshold—and we credit Rate Schedule 17 (Grant County’s adjusted rate schedule) for keeping demand from these evolving industries in check,” says Grant County PUD spokesperson Christine Pratt. She remembers when the volume of new hook-up requests received from cryptocurrency businesses during the last big spike in 2017 totaled approximately 2,000 megawatts of power—or more than three times what the utility needed to power the entire county.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]Global Bitcoin operations consume more power than the Netherlands or Philippines. —University of Cambridge estimate[/perfectpullquote]

“Cryptocurrency is an exciting and growing field and one that industry watchers say can be applied to a variety of applications, but its design and competitive nature requires an ever-increasing amount of electricity for each calculation cycle,” says Pratt. “Unbridled growth of cryptomining isn’t sustainable under current conditions at this utility. If nothing else, this region’s low-cost electricity has really forced us to learn more about it.”

Andy Wendell, Chelan County’s PUD director of customer service recalls similar eye-rubbing applications a few years back from new cryptomining businesses.

“Some of them were requesting over 200 megawatts of power,” Wendell says. “To put that in perspective, our entire service territory with all our customers of about 50,000 residential, commercial and industrial customers combined uses an annual average of right around that.”

Public shaft?

How at odds is cryptocurrency mining with energy conservation and other environmental concerns in the Columbia River Basin and beyond? And why should large public supplies of hydroelectric power be used to support the likes of Bitcoin, Ethereum, Ripple, Dogecoin and other speculative currencies, which exist primarily to avoid government controls?

Community asset: The 1908 Old Wenatchee Bridge connecting Wenatchee and East Wenatchee was the first U.S. highway bridge to span the Columbia River. Photo by cmh2315fl/Creative Commons

These are touchy questions for PUDs, which operate with a legal mandate to supply energy neutrally and equitably to all of its customers.

“We’re allowed to set our own rates based on cost of service and various risks presented by markets, operations and customer groups, but the law is the law,” says Grant County PUD’s Pratt. “Our own value judgements can’t factor into it.”

MORE: Electric cars and dams: An uncomfortable connection

“It’s a good question and one that I’ve personally grappled with ever since I was introduced to cryptocurrency mining,” says Chelan County PUD’s Wendell. “We value energy conservation here and invest heavily in it. And while a lot of our industrial, commercial and residential customers are also investing in partnerships with utilities in conservation management, that does not appear to be a priority with the cryptomining industry.

“The environmental attributes that hydroelectric power offers compared to using fossil fuels is likely a better strategic move politically for cryptocurrency miners who have targeted the Columbia River Basin. But we do have concerns as a utility of the long-term sustainability of cryptocurrency mining and blockchain technology as it relates to conservation.

“It’s a large consumption of energy,” concludes Wendell. “And while things have settled down here from those early days, they’re still using what they can.”

Columbia Insight contributing editor Jordan Rane is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in CNN.com, Outside, Men’s Journal and the Los Angeles Times.

Acknowledging the Central WA power and environmental issues, keep in mind that the fiat system consumes massive amounts of energy running and keeping the all of the central banks afloat. So do VISA, MasterCard, PayPal, etc. – these using dinosaur, petroleum-based energy infrastructures. And, the banking and transactional systems are far more corruptible and parasitic on the people because power and information are centralized.

The crypto currency movement encourages the building and use of renewable sources of energy that were less viable beforehand due to the limited number of consumers. Crypto coin mining is not profitable to the miners unless they are using cheap, renewable energy, e.g. dams in China, geothermal in Iceland and wind parks in Norway. Already, new algorithms requiring far less power consumption for crypto currencies have been developed. The market will sort out inefficiencies moving forward. Every new idea has to start somewhere. Bitcoin was the beginning. I expect to see more and more energy/environmentally conscious developments.

Decentralized blockchain systems facilitate a shift in power, wealth, privacy and security – something the centralized financial systems (and the likes of Bill Gates) are loathe to relinquish. As for “imaginary prizes,” how is bitcoin any more imaginary than the Federal Reserve printing money out of thin air?!

Good points Lynn. I didn’t see a mention in there for the vast amounts of fossil fuels used by the US military to back the almighty dollar. Decentralize!

When the dam is generating more power than the traditional consumers require where did the excess power go?

It seems to me the company producing energy would love a buyer of last resort so they can sell every last joule to market.

If/when traditional base load requires more power the Bitcoin operations can easily shut down temporarily.

Also what are the environmental impacts from mining Bitcoin with an existing hydroelectric facility? Nobody had any environmental concerns with the aluminum plant using this excess energy?

I suggest building more renewable power generation, and getting Bitcoin mining hooked up as soon as the turbines spin, then building out the infrastructure from there.

Stranded energy converted into monetary energy, transferable across the World Wide Web with a button click. An energy producers dream.

Thanks for sharing such information with us. Love to read these type of content. I would like to know more information on this.