The East Fork Lewis River Floodplain Reclamation Project aims to repair salmon habitat. Some question its methods

Water work: A massive effort is underway to restore part of the East Fork Lewis River, which enters the Columbia River about 15 miles north of Vancouver, Washington. Photo: Native Fish Society

By Aaron Gilbreath. September 28, 2023. Decades of gravel mining and flooding have impacted native fish and local communities in southwestern Washington’s Lower East Fork Lewis River watershed.

The Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership (LCEP) will use a new $5.4 million-dollar grant and other funds to try to reverse those impacts by restoring salmon and steelhead spawning grounds and protecting property from erosion and floods.

Not everyone agrees that the organization’s plan will achieve its goals, but most can agree that the East Fork is a special watershed that deserves restoration of some kind.

Late this summer, the Washington Department of Ecology awarded a total of $63 million dollars in grants to 12 groups in the state to fund ecological restoration and reduce flood risks to people and property. LCEP was one of them.

It took the group a decade to develop The East Fork Lewis River Floodplain Reclamation Project.

Combined with $7.06 million from the Washington Recreation Conservation Office’s Salmon Recovery Funding Board, and $7.5 million from the Department of Commerce’s National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, this new $5.4 million grant brings the partnership’s budget to its $20 million goal—enough to get its project underway.

Stretching three miles from Lower Daybreak Park, northwest of the town of Battle Ground, to a bit below the Ridgefield Pits, this reclamation project is the largest habitat restoration project ever implemented on the Lower East Fork Lewis River.

Pit stop: During the floods in the 1990s, nine abandoned gravel pits at river mile 7-8, known as the Ridgefield Pits, were overtaken by the river. Photo: LCEP

A nonprofit consortium of community members, scientists and educators, the Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership focuses its work on the final 146 miles of the 1,243-mile-long Columbia River, from Bonneville Dam to its mouth at the Pacific.

The East Fork Lewis River represents a small fraction of that enormous watershed, but this river remains undammed, is located near one of Washington’s fastest growing cities and offers a unique opportunity to preserve a thriving population of the Pacific Northwest’s imperiled anadromous fish.

The East Fork has remained a high priority for LCEP, as it has for a number of local groups, including the Lower Columbia Fish Recovery Board, the Cowlitz Indian Tribe, Friends of the East Fork and Columbia Land Trust.

“The big opportunity is to restore three outstanding river miles of the East Fork of the Lewis River back to its historic, pre-mining, natural condition,” Jasmine Zimmer-Stucky, the Partnership’s Public and Legislative Affairs Specialist, told Columbia Insight. “But this project is also slated to increase recreation opportunities and create more access to the river for people, while also addressing serious erosion and flood issues that currently threaten county-owned facilities, homes and businesses.”

Not everyone agrees how to go about restoring the river.

The river

Named after former Hudson’s Bay Company employee Adolphus Lee Lewis, who homesteaded near the Lewis River’s mouth in 1845, the river funnels Cascade Range snowmelt under Interstate 5 and into the Columbia River, in southwest Washington.

The Lower East Fork Lewis River is the Lewis River’s largest tributary, and it’s significant because it’s one of the area’s few undammed rivers that still supports five wild, native salmonid species: coho, chum, fall chinook salmon and winter and summer steelhead.

Five of the major tributaries that feed the East Fork Lewis River also rear significant amounts of steelhead, salmon fry and juveniles, the Friends of the East Fork reports.

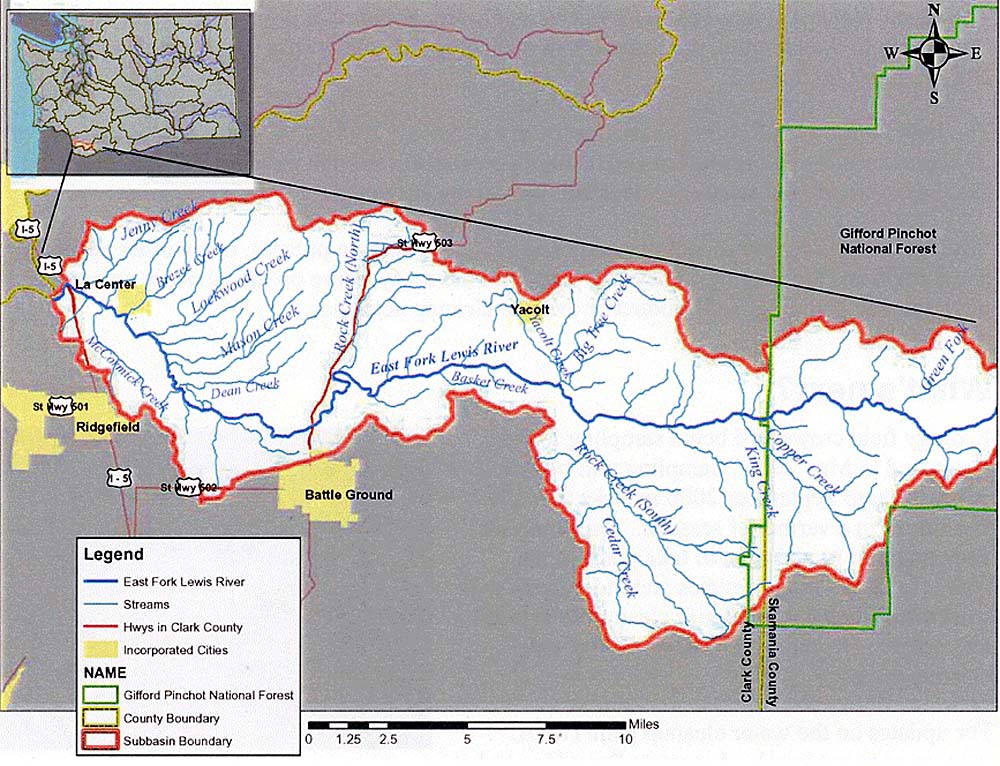

Map: Friends of the East Fork

People who fish know the East Fork.

The largest steelhead ever caught in Washington came from this river. And the East Fork is a designated wild steelhead gene bank. This means no on-site fish hatcheries have significantly altered the wild stock’s gene pool, and stocking has ended to protect wild fish from the effects of hatchery programs.

“That makes the East Fork a key component of the recovery of wild salmon and steelhead in the larger Columbia River Basin,” said Zimmer-Stucky.

Although undammed and free of a hatchery, the East Fork itself is far from untouched.

Changes to the river

Between 1930 and 1975, mining operations removed gravel directly from the floodplain.

Mines built roads, removed significant amounts of the natural downed timber from the channel and cut standing trees—materials that help regulate water temperature and that spawning salmonids use for cover when laying eggs.

In 1995 and 1996, a major flood altered the floodplain’s structure further and left sections of it more susceptible to erosion.

The Ridgefield Pits, located at river miles 7-8, were initially adjacent to the river. Earthen levees were built to separate the water from the abandoned quarries.

The floods shifted the river’s course, breaching the levees.

Now the East Fork flows through nine pits. They’re part of the channel.

The state of native fish

According to the Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership, when the East Fork broke through the bank and started flowing through the Ridgefield Pits, it eliminated salmonid spawning habitat in that section and significantly reduced rearing opportunities.

LCEP also told Columbia Insight that very few salmon currently lay their eggs in the Ridgefield Pits section of the river.

The water in the pits can get warm during late spring and summer. Salmon and steelhead are sensitive to water temperature.

Strong flow: With headwaters in Skamania County, most of the East Fork Lewis River basin lies within Clark County. Photo: Friends of the East Fork

LCEP states that this warm water can act as a thermal barrier that discourages migrating fish from proceeding into the upper portion of the watershed to spawn.

Simultaneously, the pits’ unnaturally warm waters favor fish like the northern pikeminnow, which, although native, prey on juvenile salmon, further impacting salmonid’s ability to reproduce.

These predators are a significant threat to the East Fork’s juvenile salmon.

By removing the pits, planting trees, re-grading the floodplain and returning it to one approximation of pre-colonial conditions—with meandering channels and gravel bars—LCEP believes that the East Fork Lewis River Floodplain Reclamation Project can improve spawning and ensure healthy, wild salmonid populations.

Not everyone agrees.

Another interpretation

Dick Dyrland, a retired U.S. Forest Service hydrologist who now serves as president of the nonprofit Friends of the East Fork, has serious concerns about LCEP’s approach to restoration.

Before LCEP received its recent funding, people weighed in at public meetings attended by fishermen, concerned citizens, members of stream restoration groups and environmental organizations.

After hearing the proposal, Dyrland and three other scientists submitted written statements and documents detailing technical reasons why The East Fork Lewis River Floodplain Reclamation Project would not work.

Dick Dyrland. Photo: Friends of the East Fork

“We were not listened to,” Dyrland told Columbia Insight.

Dyrland believes that this group of scientific voices was eventually cut out of the conversation when LCEP quit responding to them.

Dyrland says his group included experienced scientists with technical backgrounds who had worked around the West, the United States and overseas, and had significant experience in the field.

The scientists weren’t saying that the East Fork didn’t need a restoration project. They were saying that LCEP’s proposed design wouldn’t achieve its stated goals of improving salmonid spawning grounds and protecting healthy fish populations.

“We want to see a project done there,” Dyrland said. “But we don’t want it to fail.”

Their different approaches were technical.

According to Dyrland, records show that, in 100 years’ time, human activities changed the East Fork from a cold river with suspended sediment and natural pools to a wide, shallow, unstable river with a huge bed load. (Bed load is the material that rolls and bounces along the bottom of a waterway, compared to the suspended load, which moves in the water.)

Dyrland suggested that East Fork restoration implement a one-channel design. This would narrow and deepen the channel and regulate water temperature, and it would handle the large bed load.

According to Dyrland, LCEP’s proposed three-channel design would ensure a wide, shallow river that will lead to hotter water temperatures and issues with sediment.

“That’s a bad design for fish,” he said. “The river won’t support that.”

As a career hydrologist and activist, Dyrland has designed or assisted the installation of over 22 habitat and fish passage restoration projects—many on the East Fork. He’s performed extensive stream monitoring and evaluation, and helped file three Clean Water Act lawsuits to stop activities that were harming the East Fork.

In 2016, the American Fisheries Society awarded him the Presidents’ Fishery Conservation Award.

As a resident of Ridgefield, Wash., close to the East Fork, he says he has a vested interest in the watershed’s well-being, not a fiscal interest.

He harbors concerns about the experience and approach of scientists at LCEP and does not believe their plan is the most ecologically effective restoration plan.

Paul Kolp, restoration program lead at the Estuary Partnership, disagrees, pointing to, among other things, the extensive, multi-year and multi-agency review process the project has passed through.

“By recreating a river with highly connected floodplains that once existed in the Ridgefield Pits portion of the project—complete with a dominant channel, side channels, wetlands and alcoves to support a diversity of species, including salmon at all life stages—the Estuary Partnership is following the overwhelming guidance provided by a technical advisory group,” says Kolp. “Reconnecting rivers to floodplains benefits water quality, reduces non-native plants and predation on juvenile salmonids and improves the food-web, which benefits both aquatic and terrestrial species. Beyond benefits for salmon, allowing the river to flow across its historically wide floodplain lowers the intensity of flood events and harmful erosion by giving the river more room to expand and adjust naturally.”

[An earlier version of this story did not include Kolp’s quote. —Editor]

Recreational opportunities

On the far outskirts of greater Vancouver, Wash.—one of the state’s fastest-growing cities—and near towns like La Center, the Lower East Fork watershed is populated.

“The watershed has seen a 47% increase in human population since 2000,” according to a 2021 Washington State Department of Ecology report.

Erosion and floods have exposed some homeowners, businesses and Clark County properties like Daybreak Park and a maintenance facility, to damage.

Restoring the floodplain will alleviate some of the erosion risks upstream from the Ridgefield Pits.

Recreation also draws people to the area.

The East Fork is considered a gem of southwestern Washington, with beautiful waterfalls, outstanding fishing, boating and birding opportunities. To that list, LCEP will help add a greenway.

“This project dovetails perfectly with Clark County’s vision for a greenway trail from Daybreak Park all the way down to Paradise Point State Park,” said Zimmer-Stucky. “So it’s been in the county’s legacy land program plan for years to acquire and restore access along that three-mile stretch of river.”

She said that restoring the gravel pits is a key element of achieving that vision.

Years for results

LCEP will spend the next year or so going through a rigorous permitting process before it breaks ground.

The organization expects it to take three to four years to restore and re-vegetate the floodplain—the project’s heavy-machinery construction phase. This involves re-vegetating over 100 acres with native trees and shrubs, removing the old levees, filling the pits and regrading the floodplain and placing large amounts of woody debris and structural elements back into the river.

As many as 16 million wild steelhead and salmon once spawned in the Columbia River.

Approximately 90% of the remaining 3 million are hatchery fish.

Protecting the East Fork’s wild fish—runs that survived over a century of commercial fishing, canneries, dam-building, logging and mining—is critical to preserving the iconic natural heritage of the entire Pacific Northwest.

It will take years to determine whether LCEP’s approach is the most effective way to achieve that goal.

Mr. Gilbreath,

It is unfortunate that you did not seek out more expert opinions on this project. This project has undergone extensive technical review at both the regional and statewide levels. This includes review by a regional Technical Advisory Committee, the Washington Salmon Recovery Funding Board (SRFB) State Review Panel, a local workgroup created specifically for this project, as well as multiple agency experts. Before any earth is turned, this project must also secure the approval of multiple regulatory agencies, including the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

We appreciate that Columbia Insight presented different perspectives on this project – large scale projects indeed warrant a high level of scrutiny to ensure limited funds are being spent wisely. That scrutiny has already occurred with this project. The technical review process was comprehensive, inclusive, and all voices were heard and carefully considered during project development. While there is always some level of uncertainty with any habitat restoration work, the proposed design is overwhelmingly supported by the diversity technical experts who have reviewed this project. That is unfortunately not captured in your article.

The dissention you are highlighting represents a minority opinion grounded in a restoration philosophy that would force a channel condition that is not supported by historic or current watershed processes. It fails to recognize that river channels are dynamic and need to move across their floodplains over time. This project seeks to return an important reach of the regionally significant East Fork Lewis River to condition that will once again provide spawning and rearing habitat for salmon and steelhead, in a manner that reunites the river with its floodplain. It does not prescribe how the river should flow, but rather allows it to adjust to changing environmental conditions while sustaining habitat forming processes.

Watershed restoration is an evolving science, and it is important to adjust approaches based on what we have learned over the last 20 years. This project is grounded in the state of the science and is broadly supported by both technical experts and the local community. As with all restoration work, how the fish respond will ultimately reflect level of success as noted.

Thank you.

Steve Manlow

Director, Lower Columbia Fish Recovery Board

I wish to thank Aaron Gilbreath for his story “Is this $20 million river restoration funding being spent wisely?”. I am in full support of Richard Dyrland on his assessment of the Ridgefield Pits Project and would like to present additional information on the project. I am in favor of a restoration project for the Ridgefield Pits, and feel it is long overdue, but believe the proposed project by Lower Columbia River Estuary Partnership (LCEP) is inadequate and flawed. Creating a three-channel river and filling the mined-out pits with porous fluvial material (gravels) will not restore salmon and steelhead runs on the East Fork. River water will continue to flow through the porous pits. The major limits to the East Fork are low summer flows and high summer temperatures. A multi-channel system will enhance reduced flow and higher stream temperatures. Having three channels reduces the depth in each channel, creating less flow which is not good for fish. River water will continue to flow through the filled pits and during normal river flow the water will be too low for fish passage, upriver migrants and down river smolts (three channels). During high flow the river will have a heavy load of gravel, cobbles and boulders. As the river flow approaches the three-channels it will begin dropping much of this heavy load forming river bars and initiating changes in the river. Splitting the river water into three channels reduces the river water velocity. Filling in the pits will destroy much needed waterfowl and water bird habitat. A river implies one channel not three. I am a retired Civil Engineer and Geologist from the Corps of Engineers. Also spent over eight years as a Geologist with the US Forest Service and worked for Clark County as a Hydraulic Engineer and Hydrologist developing stormwater runoff master drainage plans.

Oregon State economist professor William Jaeger and Mark Scheuerell, a biologist with U.S. Geological Survey and the University of Washington, looked at 50 years of data for native and hatchery salmon and steelhead return data from Bonneville and Cascade Locks. The two also reviewed decades of spending on habitat restoration and hatcheries programs and found neither are helping salmon and steelhead. Article in The Columbian, August 5, 2023, Saturday, on front page: “Return(s) on investment: Restoration spending in the Columbia River Basin and increased abundance of salmon and steelhead”. They looked at the investment of $9 billion of restoration spending on Columbia River Basin (CRB) over the past four decades to improve salmon and steelhead runs and found no improvement. This is not surprising because it is common knowledge the salmon and steelhead runs have continued to drop along the Pacific Coast from California to Alaska.

The success Lower Columbia Estuary Partnership (LCEP) claims for Steigerwald Lake Project (SLP) is not true especially for chinook. Claim is a fabrication (lie). The more often and longer you tell the lie, misleads the public about the true success of SLP. “BPA and Corps restored more than 7,000 acres of estuary habitat since 2007 (BPA EA 2019) “, but the salmon runs including chinook have continued to decline to record lows. I talked to a legal entity in Washington D.C. prior to construction of SLP, and he informed me it is unlawful for the USWFS to use National Wildlife Refuge lands to create shallow water habitat. They wanted $25 to $50K to go to court but unfortunately, I was unable to get that amount. A number of fish biologists I have talked to, maintain chinook salmon will not use the shallow water habitat at SLP because it is too warm. The SLP has opened the Steigerwald Lake National Wildlife Refuge to PCB’s that are in the Columbia River. PCB’s have been found in high levels in freshwater clams in the Columbia River. They have also been found in sturgeon and lamprey. Are waterfowl next? In the same article (5-8-22) RNWR management indicated they had found silver salmon and lamprey on the project site. There was no discussion about chinook on the project site. Not surprised with information presented above. Even though, according to the project sponsors the primary objective was to provide chinook habitat. SLP was really for recreation as highlighted in The Columbian (Sunday, 5-8-22). “The trail system is longer, and it’s also a lot more diverse.” “—- the trail now weaves into and out of the refuge and crosses a couple of channels with new bridges.” Two newly constructed Kiosks are on site. In other articles in The Columbian, Ridgefield National Wildlife Refuge (RNWR) management only talked about the recreational features of the SLP, nothing about salmon and waterfowl. RNWR manager gave a presentation on SLP at a non-profit organization and all he discussed was the recreational features of the project. After his presentation, I asked him about the birds. He slammed his laptop closed. The woman from USFWS regional office helping him told him he could not leave. He said he was leaving. She apologized and picked up the remaining equipment. He also left the hunting community off of the stake holders team.

Below is a quote from Steve Manlow (Director, Lower Columbia Fish Recovery Board) and Shauna Hanisch-Kirkbride, PhD, Managing Director Lower Columbia Fish Enhancement Group: “And, as you say, ‘the river will give us the answer’ (or as Steve said, the fish will”. I could not agree more, the fish are giving us the answer: the salmon runs have continued to decline on the Columbia River for nearly four decades, but neither director is listening. There has been $9 billion dollars spent on restoration with no increase in fish runs.

I have some additional comments on the story, “Is this $20 million river restoration funding being spent wisely?” Clark County has a poor track record on conserving, protecting, and enhancing wildlife (especially fish) habitat and the environment. A primary reason the East Fork shifted into the Ridgefield Pits (RP) was the poor to no enforcement by Clark County on the gravel mining operators. The operators were allowed to mine gravel beyond and below the toe of the containment dike. Their action destroyed the integrity of the dike and led to the failure of the dike long before the 1996 flood. The County has continued, as you read these comments, with their policy of non-enforcement of gravel and quarry mining. The Friends of the Columbia River Gorge took legal action against the county to force closure of the Zimmerly Pit in Washougal, WA. The operator was mining illegally and causing environmental damage. There are numerous other infractions at other quarries and pits in Clark County.

The Clark County Council (CCC) recently approved Surface Mining Overlays (SMO) for two quarry sites in the North Fork Lewis (NFL) Drainage. One is south of Woodland and several hundred feet south of the NFL, and the other is in the headwaters of Chelatchie Creek which is a tributary of Cedar Creek that flows into NFL. Both have the potential to have impacts to their respective drainages as the mining at the Ridgefield Pits did to the East Fork, especially with the policy of no to poor enforcement of mining operations by the county. The Clark County attorney told the council that the SMO overlays were illegal (broke the law). Some County staff also said the SMOs were illegal. Friends of Clark County (FOCC) took legal action against the County Chelatchie SMO . The county contractor for the Portland Vancouver Junction Railroad followed the CCC lead on illegality and constructed a road in the headwaters of Chelatchie Creek, filling in wetlands and killing coho and steelhead, which both are threatened. The Corp of Engineers (COE), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) and Washington State Department of Ecology (DOE) are investigating. A stop work order has been issued to the contractor.

Clark County’s critical area ordinances are not compatible with Washington State and federal directives to conserve, protect, enhance wildlife (especially fish) habitat and the environment . The county has developed their own plan they call “show their work” for evaluating riparian habitat along natural streams and water bodies. The plan is not site specific and doesn’t include changes in topography, stability and geology including soils. There is no analysis of possible success and failure (goals) of riparian corridor widths. The plan is based on arbitrary criteria that has been developed for ease of implementation for development. These ordinances do not include high profile recommendations of the Growth Management Act (GMA). 1. The use of Best Available Science (BAS). 2. Provisions to protect, conserve and enhance anadromous fish and their habitat. 3. The use of Site Potential Tree Height (SPTH) in assessing riparian habitat along non-fish bearing streams. The Clark County ordinances also don’t include federal and state provisions for reducing global warming. The critical area ordinances have a huge impact on non-fish bearing streams. These non-fish bearing streams were fish bearing streams in the not too distant past and if properly managed could become fish bearing streams in the future. The ordinances reduce the riparian habitat along these non-fish bearing streams significantly which impacts all wildlife, especially fish. These impacts extend downstream to larger fish bearing streams and rivers and affect other wildlife. The riparian habitat along streams and rivers provides a buffer to trap plastics, pollutants and sediment; prevents erosion and provides refuge for wildlife; provides bank stability, scenic value , nutrients and flood storage; and lowers water temperatures. If these ordinances are put in place, fish bearing streams and rivers may become non-fishing bearing streams and rivers. The salmon and steelhead are in our review mirror and that is sad. I have been informed Washington State Department of Ecology (COE) has reviewed the ordinances and will not approve them. Clark County requested the review.

For all of these reasons, I would recommend removal of Clark County from the Lower Columbia Fish Recovery Management Board, since they clearly don’t support conserving, protecting and enhancing wildlife (especially fish) habitat and the environment. Save the planet, wildlife and the environment.

I am a retired Civil Engineer and Geologist from the Corps of Engineers. Also spent over eight years as a Geologist with the US Forest Service and worked for Clark County as a Hydraulic Engineer and Hydrologist developing stormwater runoff master drainage plans.

The lower EFk Lewis is too warm to support production of salmonids except perhaps tule fall Chinook. The desired multi-channel stream pattern already exists, if the water was cold in summer it would be VERY productive, as you’d expect to find in similar rivers further North or perhaps at a higher elevation.

The DOE did a stream temperature survey about a decade ago which confirms the water flowing into the lower EFK Lewis where the pits exist is too warm, which means without cooling the water upstream first there is no way to cool the water downstream through the project area.

In addition, tide water begins immediately downstream of the Ridgefield Pits which historically would have been filled with large wood collections covering the entire floodplain from La Center to the confluence with the NFK Lewis. Today, there is virtually NO COVER in the water which allows for massive predation by native and non-native fish as well as birds and mammals.

So, without cooling the water below 68 degrees through the entire summer, and installing massive channel blocking amounts of large wood cover, the funds being spent there in the hope of increasing salmon runs would be better spent elsewhere.

It is sad to know that tax payer funds are often mis-spent because the “technical” committees overseeing and approving project funding do not monitor project success over time. In the case of the EFKLewis there have been many projects previously funded but none have shown a clear benefit to targeted species.

The reality is no projects can increase salmon/ steelhead/ trout habitat function if the water is too warm (>68F in summer) and/ or too simplified (no instream cover). This project WILL NOT increase adult salmon or steelhead runs but it will benefit the landowners, government agencies and river recreation users who live, work and play in the lower EFK Lewis River.

The lower EFk Lewis is too warm to support production of salmonids except perhaps tule fall Chinook. The desired multi-channel stream pattern already exists, if the water was cold in summer it would be VERY productive, as you’d expect to find in similar rivers further North or perhaps at a higher elevation.

The DOE did a stream temperature survey about a decade ago which confirms the water flowing into the lower EFK Lewis where the pits exist is too warm, which means without cooling the water upstream first there is no way to cool the water downstream through the project area.

In addition, tide water begins immediately downstream of the Ridgefield Pits which historically would have been filled with large wood collections covering the entire floodplain from La Center to the confluence with the NFK Lewis. Today, there is virtually NO COVER in the water which allows for massive predation by native and non-native fish as well as birds and mammals.

So, without cooling the water below 68 degrees through the entire summer, and installing massive channel blocking amounts of large wood cover, the funds being spent there in the hope of increasing salmon runs would be better spent elsewhere.

It is sad to know that tax payer funds are often mis-spent because the “technical” committees overseeing and approving project funding do not monitor project success over time. In the case of the EFKLewis there have been many projects previously funded but none have shown a clear benefit to targeted species.

The reality is that increasing salmon/ steelhead/ trout habitat function is impossible if the water is too warm (>68F in summer) and/ or too simplified (no instream cover). People need to be more vigilant regarding how these funds are spent by insisting on proof of concept, or has been said “show me the fish (money!). There is very, very little data showing a direct cause and effect in terms of salmon habitat restoration anywhere in the PNW let alone in lower EFK Lewis River where summer water temperatures routinely exceed 80F.

Read the Ecology stream temperature report for the EFK Lewis, it’s really the key to understanding what limits salmon/ steelhead production in the watershed and especially in the lower river where this project, and others before it, is located.

I was once deeply involved in habitat restoration projects in the EFK Lewis and actually built logjams in the area being proposed for further restoration. During that time we did extensive stream habitat surveys and fish surveys to determine the success of our work. What we found is that in spring there were numerous juvenile fish using the LWD structures we installed as well as the tributary and side-channel habitats. But, as summer progressed and the water temperatures increased we noted the complete disappearance of juveniles in the Ridgefield Pits area.

We quickly determined the lower EFk Lewis is too warm to support production of salmonids except perhaps tule fall Chinook. The desired multi-channel stream pattern already exists (see aerial photos) so IF the water in the river was cold in summer it would be VERY productive, as you’d expect to find in similar rivers further North or perhaps at a higher elevation. But it’s not, it’s too warm for salmonids and there’s nothing anyone can do to change that fact, at least not in the Ridgefield Pit area.

The DOE did a stream temperature survey about a decade ago which confirms the water flowing into the lower EFK Lewis where the Ridgefield Pits exist is too warm, which means without cooling the water upstream first there is no way to cool the water downstream through the project area. We measured 80F in the main channel which is lethal to salmonids.

In addition, tide water begins immediately downstream of the Ridgefield Pits which historically would have been filled with large wood collections covering the entire floodplain from La Center to the confluence with the NFK Lewis. Today, there is virtually NO COVER in the water which allows for massive predation by native and non-native fish as well as birds and mammals.

Tidewater is even warmer than the Ridgefield Pits, and without cover there is virtually no survival through summer because warm water directly kills salmonids but also weakens them so that predators can easily capture and eat them due to lack of cover or thermal refuge.So, without cooling the water below 68 degrees through the entire summer, and installing massive channel blocking amounts of large wood cover, the funds being spent at Ridgefield Pits would be better spent elsewhere.

It is sad to know that tax payer funds are often mis-spent because the “technical” committees overseeing and approving project funding do not monitor project success over time. In the case of the EFKLewis there have been many projects previously funded but none have shown a clear benefit to targeted species.

The reality is that increasing salmon/ steelhead/ trout habitat function is impossible if the water is too warm (>68F in summer) and/ or too simplified (no instream cover). People need to be more vigilant regarding how these funds are spent by insisting on proof of concept, or has been said “show me the fish (money!). There is very, very little data showing a direct cause and effect in terms of salmon habitat restoration anywhere in the PNW let alone in lower EFK Lewis River where summer water temperatures routinely exceed 80F.

Read the Ecology stream temperature report for the EFK Lewis, it’s really the key to understanding what limits salmon/ steelhead production in the watershed and especially in the lower river where this project, and others before it, is located.

I just flew over the area in my Super Cub today 8/12/25 and they have a make shift bridge crossing the river running heavy equipment. They are washing down the bridge with water from a water truck and all the runoff is going directly into the river. Where is the EPA. I could never get away with this destruction in my own backyard. I don’t see how this is good for the fish or environment.