Washington’s Climate Commitment Act aims to reduce carbon emissions 95% by 2050. But passing a law and enforcing it are different things

Making allowances? Many Washington businesses must start adapting to new carbon emissions regulations. Some get a pass. Photo: Chris Leboutillier/Unsplash

By Eli Francovich. February 9, 2023. Prior to moving to Washington for a job with the Department of Ecology, Claire Boyte-White was a freelance writer focused on entrepreneurship, finance and investment. In this capacity, she explained the complexities of the financial world for a general audience.

In December 2021, however, she changed careers and started at a job that a year prior hadn’t existed.

Her title? Communications Specialist for the Climate Commitment Act, Washington’s newest legislation aimed at slowing climate change.

And while on its face the act has nothing to do with high finance there are parallels.

The Climate Commitment Act is a carbon cap-and-invest program under which the amount of carbon some Washington industries may produce per year is capped.

The law, which was passed in 2021, went into effect on Jan. 1.

Its carbon-emissions limit is slowly lowered over time, with a goal of reducing the state’s emissions 95% below 1990 levels by 2050.

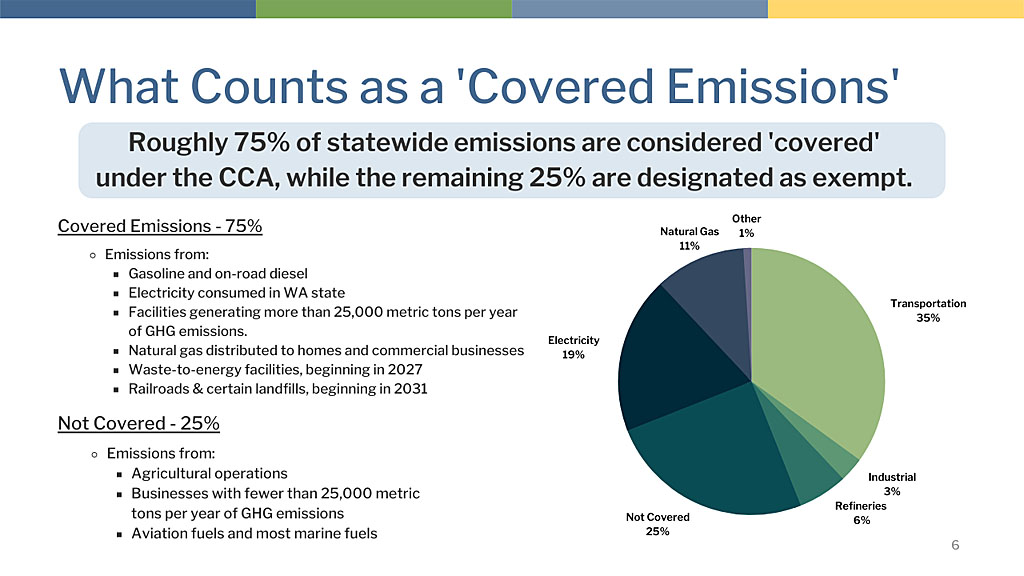

The law applies only to industries that produce more than 25,000 metric tons of carbon per year. Certain industries have been exempted, although the state says 75% of statewide emissions will be covered under the program.

Qualifying industries, however, must meet the emissions limit set by ecology each year or buy allowances to burn carbon in excess of the cap.

Those allowances will be auctioned off quarterly with each allowance allowing the owner to emit one metric ton of CO2.

While the state has set the maximum and minimum prices of those allowances (for 2023 it’s $22 and $81), the exact price will be dictated by the market.

As the overall cap lowers, the price per allowance will increase, thus incentivizing companies to decarbonize.

Money from those allowances, projected to be more than $1 billion per year, will go toward climate adaptation and decarbonization efforts, as well as clean air initiatives.

What could go wrong?

The CCA model has been heralded elsewhere as an effective tactic in the fight against climate change, one that—unlike taxes or direct mandates—gives companies monetary incentives to reduce their carbon footprint.

Theoretically, it’s an effective partnership between the long arm of government and the power of supply and demand.

“They are financially incentivized to decarbonize, but they are empowered to make all of their operational decisions,” Boyte-White says.

Cap wrangler: Sen. Reuven Carlyle, then chair of the Washington Senate’s Environment, Energy & Technology Committee, co-sponsored the Climate Commitment Act in 2021. Photo: Washington State Democrats

However, cap-and-trade programs have been exploited, abused and unfairly applied elsewhere.

And while it’s certainly too soon to judge Washington’s program, understanding how it could go wrong is useful.

For an example look south to California, where a similar (although not exactly the same) cap-and-trade program has existed since 2013, one of the first in the world.

While California’s program was lauded for early successes, a 2019 ProPublica analysis found that since the implementation of the program “carbon emissions from California’s oil and gas industry actually rose 3.5% since cap and trade began.”

That investigation found, among other things, that economic and political lobbying often defanged key parts of the program and allowed the largest and richest companies to pollute more.

Strategic exceptions

Who is allowed, or not allowed, to burn carbon and/or at what price is already a concern for some in Washington.

Per the Washington law, some industries are completely excluded from the cap-and-trade program and others are given allowances for free (think of it like a free token to play an arcade game).

Notable exemptions include emissions from aviation fuel and emissions from watercraft fuel supplied in Washington but burned elsewhere.

Infographic: Washington Department of Ecology

Then there are industries given “no-cost allowances”—an allowance allows the company to burn one metric ton of carbon above the cap set by Ecology.

These industries include electric and natural gas utilities and businesses that are “emission intensive, trade exposed” industries, such as manufacturing.

The goal of that provision is to keep those industries from leaving Washington, says Boyte-White.

“They’re big companies,” she says. “Big industries can’t pivot on a dime. Give them some time to invest and decarbonization early on. And prevent leakage.”

Who could object?

But at least one company is arguing that CCA allowance provisions aren’t fair.

In December, The Grays Harbor Energy Center filed a federal lawsuit alleging the program is unconstitutional.

At issue is the fact that the Grays Harbor plant, which is owned by Chicago-based Invenergy, isn’t utility-owned and thus won’t receive a no-cost allowance.

Commitment communicator: Claire Boyte-White. Photo: Washington Dept. of Ecology

According to the lawsuit the act’s “allocation of no-cost allowances uniquely harms Invenergy. Unlike local utilities who may use their no-cost allowances to reduce, if not eliminate, their costs to comply with the CCA, it must bear the costs of ensuring Grays Harbor has sufficient allowances to cover its emissions during the CCA’s first compliance period.”

Boyte-White wouldn’t comment on the case specifically although she said broadly what is or isn’t covered by the program was decided by the Legislature.

“Any changes about program coverage would be Legislative in nature,” she says.

The Association of Washington Business also raised concerns about the program’s impact on the 7,000 businesses they represent arguing in a 2021 letter to the Legislature that the program erodes “the competitive advantage” Washington’s cheap power has traditionally provided.

“This pressure makes it difficult for existing small businesses to continue and much more difficult for entrepreneurs to start one,” the letter states.

Just application

One way that Washington’s program is notably different than California’s cap-and-trade effort is in its commitment to cleaner air, in conjunction with lower emissions.

Surprisingly, after California’s law was passed a study found that air quality deteriorated in Black and Latino communities, raising serious questions about environmental justice.

To offset that, Washington has created an initiative in conjunction with the cap-and-trade program to improve air quality in “overburdened” communities.

An environmental justice council will have input on how money raised by the CCA is spent.

Additionally, 35% of funds raised by the program must be invested in projects that benefit at-risk communities and a minimum of 10% must go to projects with tribal support.

While the GOP remains hijacked by billionaires and fossil-fuel interests, Democrats should be honest about the efficacy of carbon pricing. There is no evidence that a politically feasible price on current emissions has significantly reduced emissions. For a dose of reality, the recent book, Making Climate Policy Work by Cullenward and Victor, expertly analyzes the EU ETS, RGGI, and California-Quebec cap-and-trade systems to explain how they work in the real world, as opposed to the theory.

In short, cap-and-trade effectively acts like a carbon tax because auction prices would go ballistic if there wasn’t an oversupply of allowances. The price elasticity of fuels is far too low for a tax or fee to have significant impact. (Hey, we learned that in the 1970’s oil crises.) Thus, any cap is popular fiction, sector-specific policies are necessary to do the heavy lifting in emissions reductions, and the revenue generated tends to become green pork. A carbon tax is quite regressive, necessitating a refund of large portions of the revenue to low-income families to pay the fuel bills. The Exxon lobbyist caught in the Greenpeace sting confirmed that Big Oil supports a carbon tax—because they know that it doesn’t work and it’s good for distracting, dividing, and delaying effective policies.

The actual design of Washington’s CCA (cap-and-trade) is hidden in Table 88 on page 193 of the Act’s Preliminary Regulatory Analyses. This shows that all sectors are assumed to be 90% decarbonized by 2050–when only the electricity sector currently has policies to do that heavy lifting. Thus, the CCA market is designed to reduce emissions 10% over 28 years, or less than 0.4% annually, while the critical and urgent need is 7% reduction every year until 2030.

What are effective policies? 1) Mandates, like the Clean air Act, Clean Water Act, and Endangered Species Act implemented. If the Endangered Species Act had created a market, then we’d just have deranged dentists paying $100,000 to shoot the last of the most endangered animals. 2) Price future emissions, the emitting infrastructure that locks in emissions over the lifetime of the vehicles or buildings—which were originally bought by affluent folks who didn’t care about emissions. That’s how Norway does it; California’s Advanced Clean Cars II (ACCII) policy is also an excellent structure that effectively prices future emissions by punishing automakers who build gas guzzlers and rewarding automakers who build zero-emission vehicles. ACC II will do far more to cut emissions than cap-and-trade.

Correct me if I’m wrong:

When you write “Those allowances will be auctioned off quarterly with each allowance allowing the owner to burn one metric ton of carbon

you should say Those allowances will be auctioned off quarterly with each allowance allowing the owner to emit one metric ton of CO2

When one atom of carbon is burned, it combines with 2 atoms of oxygen to make one molecule of CO2 which weighs 3,7 times the weight of the carbona alone.

When one ton of carbon is burned, it makes 3.7 tons of CO2

Hi Don: You’re right about the difference between burning and emitting. We’ve amended the sentence you refer to. Thank you for the eagle-eyed read of Columbia Insight. —Editor

to Eric Strid,

We need you to advocate this to the Governor.

Do you know how to send him an e-message?

https://www.governor.wa.gov/contact/contact/send-gov-inslee-e-message

Gov. Inslee previously eschewed pricing current emissions, due to a lack of efficacy. I don’t know his thinking now or when he signed it, but the legislature has created this new source of revenue and it’s already budgeted to support multiple agency programs. Politically, there are many uneducated climate advocates and organizations who love and adore carbon pricing; the environmental justice lobby is highly skeptical; and businesses roll their eyes and rightly complain about an ineffective tax. Large businesses will push back and sue when they can. Fossil fuel companies will simply pass the costs onto customers. Perhaps the worst economic impact is that CCA creates a significant tax for small businesses, who often run on very slim profit margins. For example farmers in eastern Washington already use the most energy-efficient vehicles they can get, and an extra dollar per gallon can be the difference between making money or not.

BTW, there’s a new, excellent tool for quantifying the emissions, economic, and health impacts of energy policy options for Washington state: the Energy Policy Simulator supported by Energy Innovation and RMI. It’s free, online, open-source, and non-partisan. It’s trivial to enter a price on carbon for selected sectors, and it immediately graphs the impacts. Applying $80 per MTCO2e (yes, CO2, not C) to all sectors cuts 2050 emissions by 6.8%, and $120 per MTCO2e cuts 2050 emissions by about 10%. The simulator confirms the overall impacts of the CCA, like the original design in Table 88–and the superiority of alternative policies like ACC II.

To cut greenhouse gas emissions 7% per year we must urgently and carefully design and implement effective policies. The good news is that doing so will save many billions by curtailing fossil fuel purchases, after a period of investing in increasingly affordable clean energy infrastructure.