Dirt Hugger in Dallesport, Washington, picks up where creation left off.

By Kathy Watson. Jul. 6, 2017. The Book of Genesis tells us God created dirt on the third day, and it was good. Pierce Louis knows what an awful lot of work that must have been, because he makes dirt too. It’s not easy being God.

Dirt Hugger, the company Louis started with partner Tyler Miller seven years ago, does something remarkable and god-like. None of us can actually create two of the essentials needed for life on earth: air and water. But Pierce and the other Huggers make the third critical element: dirt. Which, it turns out, requires menial labor, sophisticated technology, and massive, expensive equipment. It’s a story that really deserves its own chapter in Genesis.

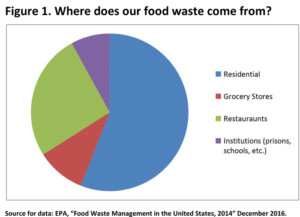

Why does composting matter? Once we create food waste—an astounding 40% of the food produced in America is wasted—we have to do something with it. In the 19th century, New York City turned pigs loose in the streets to eat garbage at the gutters. Our preferred method pretty much ever since, however, is to send it to landfills, where all those nutrients are trapped. And all the while, it could have been making soil better. Does the earth really need this creative power? In a recent New York Times story on composting, Jean Bonhotal, the director of the Cornell Waste Management Institute said, “Our soils, really, in the whole world, are pretty trashed.”

For local farms like Wildwood Farm in Oak Grove, Dirt Hugger compost is the farm’s sole fertility program. Farmer Laurel Bouret says they spread a thin layer on their fields every year and have since the company released its first dirt vintage. Dirt Hugger also makes a custom blend potting soil for starts for them. “For us, it might be more expensive than some pelleted manure, but I like knowing the whole cycle of it, that our area’s waste is being used. I’d rather buy a product made here,” she says.

The Oregon Department of Environmental Quality lists the benefits of composting:

- Reduces greenhouse gas

- Increases soil productivity

- Reduces or eliminates the need for chemical fertilizers

- Produces higher crop yields

- Improves soil porosity and water retention

Even with those lofty accomplishments, Louis doesn’t think turning all organic waste into compost is the highest and best use of the stuff. While he’s constantly on the hunt for the waste Dirt Hugger uses in dizzyingly complicated ‘recipes’ to make dirt, he sometimes turns away perfectly good waste because it’s not the highest and best use for it. A brewery called recently with spent grain, and Louis directed them to a feed lot. Better to feed animals, he says. The Environmental Protection Agency puts composting near the bottom of their Food Recovery Hierarchy.

The best possible solution to food waste?

Don’t make so much of it.

“Our society at times borders on obsession with the trivial. These discussions almost always focus on what happens at the compost site or the landfill. Almost never does anyone ask about the upstream impacts. But that’s where the majority of impacts likely occur,” wrote David Allaway, Oregon DEQ policy and program analyst in the Solid Waste Program.

“Upstream processes contribute about 20 times more domestic greenhouse gases than waste management does,” Allaway said. “Landfills are viscerally offensive to people, but when we in DEQ measure the impact of landfills versus production and upstream supply, the impacts upstream are typically 10 to 20 times higher.”

And of course, the worst use of waste is to landfill it. But composting is just one notch up from the dump. Then comes industrial uses such as energy recovery, then feeding animals, and then feeding hungry people.

“Composting is just the low hanging fruit of food recovery,” says Louis. “And there’s the job part. Every 10,000 tons of waste sent to a dump creates one job. Every 10,000 tons of waste sent to a composting facility creates four jobs.”

“Composting is just the low hanging fruit of food recovery,” says Louis. “And there’s the job part. Every 10,000 tons of waste sent to a dump creates one job. Every 10,000 tons of waste sent to a composting facility creates four jobs.”

Spend some time at Dirt Hugger, and you can easily understand why making compost is labor-intensive.

First, there’s managing all the waste that arrives, known as feed stock, to create the final rich, black, compost. There’s yard debris. There’s the beer they discard after they’ve extracted the yeast at Wy’East Labs. Theres the waste water from breweries; there’s the food waste from restaurants, and beginning May 1, there’s now the curbside pickup of food waste from homes in Hood River. Each has its own characteristics, the ratio of carbon to nitrogen. It can’t just all be dumped in a pile, and left to fend for itself.

The process starts even before the waste arrives.

“We begin with the end product in mind. We need clean feed stock to begin with to get a great product at the end,” says Louis. The company works closely with Hood River Garbage, which hauls the food waste to Dirt Hugger, to determine what household folk can go into the curbside food waste containers. Since Dirt Hugger has a post-consumer waste permit, this means it can take meat, fish, vegetables, scraps from the table, scraps from food prep. “If you eat it, it can go in the bin,” says Louis. But that’s where it ends.

No other items are allowed in the bins. Even though some of the paper items we use at home—napkins, paper plates, paper towels—might not be a problem, since they are part of the needed carbon equation. But telling people they can add those paper products is the slippery slope to sloppy feed stock. Pretty soon, people think, oh, I can just throw in this compostable fork, it’ll be fine. But that’s not always true. Some of those compostable products are made with a synthetic process that would actually violate Dirt Hugger’s organic certification. To keep it simple for the haulers and for the home users, it’s edibles only.

The Huggers keep a card, pasted on the trailer office wall, on each arriving waste stream with its characteristics, carefully mixing the cards, to create the right balance. Increasingly, part of that calculation is about salt. The food waste from restaurants and our doorsteps is very salty, which isn’t the happiest medium for growing plants. When a recipe is mixed and ready, it heads for the bed.

Temperature, moisture, air and good bugs.

Dirt Hugger practices what is called turned aerated static pile composting. All those mixed feed stocks are spread across a vast bed, and underneath it is something like an air hockey table with computerized sensors. Louis calls up the read-out from the big composting bed on a computer screen, showing how the team manages the pile for temperature, moisture and air. The more oxygen that’s pumped in from below, the more aerobic activity takes place, which makes a better product as the good bugs multiply.

They keep the temperature at a steady 170 degrees for three days which kills the bad pathogens, and encourages the most efficient microbes. That 170 degrees accomplishes something else: it kills weed seed and it breaks down hydrocarbon chains, neutralizing things like Round-Up, and helps deliver a product that is certified organic. What their process cannot do, however, is make persistent herbicides vanish. Their compost is tested to make sure it doesn’t have any, and they’ve never failed that test. But it takes a lot of care to keep items with persistent herbicides out of the process. It’s in weird places, such as horse feed. “Yep, we can’t take horse manure,” says Louis.

Keeping the compost rolling and moving after the three days on the air hockey table takes the work of two massive Rube Goldberg-looking pieces of equipment. Each costs $450,000; each is 20 years old. There’s a third of one these. It doesn’t run, but it delivers up its parts to keep the other two running, because the company that makes the machines, doesn’t anymore.

The cost of the equipment is what drives the scale of composting operations, says Louis. There’s no such thing as a mom-and-pop operation. Go big, or go home. This year, Dirt Hugger will maw through 40,000 tons of waste, spread across its nine acres.

The cost of the equipment is what drives the scale of composting operations, says Louis. There’s no such thing as a mom-and-pop operation. Go big, or go home. This year, Dirt Hugger will maw through 40,000 tons of waste, spread across its nine acres.

The near-dirt goes through a number of other sorting and winnowing processes. And here’s where more of the manpower comes in. Three of the 12 employees do one thing, full time: they walk the big rows of compost, pulling out plastic and other trash. Louis grimaces. “It’s the dirtiest job. I’ve done it.” Fred Quincy drives all the way from Skamania County to work for $12 an hour, dragging a plastic bag back and forth across the compost, rescuing us from our composting mistakes. Louis describes a few composting styles: there’s the person who tosses an entire plastic bag of carrots into the bin. “I call her the ‘Lazy Susan.'” Or the customer who carefully chops up vegetables scraps, loads them into a plastic bag, and THEN deposits the plastic bag in the bin. “I call that person Confucius.” As in, confused. As in, never imagined what a hard job Fred Quincy has.

The dirt is sifted, too, by machine, to remove rocks and ramekins, forks and spatulas. Yep, they’re all in there. Louis rescues the silverware and returns it to local schools. “One of our employees even saved the silverware to use at her wedding.”

The worry about odor.

And while all this heating and airing and flipping and sorting goes on, there is always the worry about odor.

Odor is a big battle for any composting operation, but the longer the waste sits unattended, the worse the problem becomes, so all arriving waste is mixed and covered within an hour. Walking down the rows of compost in varying degrees of completion is a nose workout. The younger rows can make your nose hairs wish they were anyplace else. But a month on, when the compost is finished, the smell of the fecund and fragrant mounds produce an unusual aromatherapy experience: here is life, ready to become cherries and kale and summer tomatoes, again.

When Dirt Hugger started out, it was located in The Dalles, on port property. It got booted for the Google plant, and at first Louis and Miller searched hard for another Oregon location. It was home, and the Oregon DEQ “is amazing” says Louis. But their nine acres in Dallesport, WA turns out to be perfect: it’s downwind from any housing, it’s right on a major road, and they’ve been able to work out some backhaul options for local trucks that were returning empty to Portland. Just in case, though, downwind or not, Louis is a good neighbor to the people in Dallesport, across the road and west of them. Those folks can bring their yard clippings and drop them off for free, for instance. The fish smoking operation across the highway gets to dump its fish bones and guts for free too.

Louis is a true believer in what he does, and the belief is infectious. He loves dirt. “We’ve always been philosophically driven,” he says. It may be why Quincy drives such a long way to bag plastic.

Trash, Odor and Money

TOM. That’s what Louis calls his biggest challenges: Trash, Odor and Money. Can he get clean feed stock? Can he manage the smell? Can he keep the money rolling in to repair those $450,000 machines and pay his people enough to bring them back each day? That’s why his compost costs a pretty penny, and why he charges twice: first, it costs us to send our waste to him, and second, to buy back the finished product.

The good news for the future of Louis’ TOM challenges is that composting is growing, ton by ton, city by city. In the first year Portland started curbside food waste pickup in 2011, garbage dropped by 38%, while collection of yard clippings and food scraps tripled. Currently, there are 39 aerobic composting facilities permitted in Oregon and Washington. Dirt Hugger’s tonnage will rise, and the compost, which sells out completely now to row crop farmers and tree fruit farmers and home gardeners, will find new markets beyond the Gorge.

The good news for the future of Louis’ TOM challenges is that composting is growing, ton by ton, city by city. In the first year Portland started curbside food waste pickup in 2011, garbage dropped by 38%, while collection of yard clippings and food scraps tripled. Currently, there are 39 aerobic composting facilities permitted in Oregon and Washington. Dirt Hugger’s tonnage will rise, and the compost, which sells out completely now to row crop farmers and tree fruit farmers and home gardeners, will find new markets beyond the Gorge.

It’s a dirty job, but thankfully, Louis, Miller and the Huggers are happy to do it.

Thank you to our business sponsors for making our work possible!

RELATED POSTS: