What happened to the female half of Klickitat County’s two-wolf Big Muddy Pack?

Half-pack: Wildlife biologists collared gray wolf WA109M in January 2021 in Klickitat County. Now his mate has gone missing. Photo: WDFW

By Dawn Stover. February 27, 2024. In April 2023, Columbia Insight reported that Southwest Washington had its first gray wolf pack in a century.

The Big Muddy Pack formed when a collared male that wandered into Klickitat County was joined by an un-collared female.

Together they met the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife’s minimum for recognition as a pack: at least two wolves traveling together in winter.

The state wildlife agency’s wolf biologist Gabe Spence told Columbia Insight it was a “big deal” to finally find a pack in the southwestern third of the state.

It seemed likely the pair would produce pups in 2023.

Now wolf experts with the agency aren’t sure the pack still exists.

And some locals are wondering if the wolf may have been intentionally killed.

Missing in action

Since October 2023, the wildlife department’s monthly updates have repeatedly noted that agency experts “conducted monitoring activities” in the Big Muddy Pack’s territory. Those activities have thus far failed to detect the female member of the pack.

The collar on wolf WA109M, the pack’s male, usually transmits his location twice a day. When he’s in rocky or heavily wooded terrain, it can take longer to receive that data.

The state’s wolf team uses the collared wolf’s last known location to look for tracks in snow and check game cameras in the area.

They can also circle over the location with an airplane or helicopter.

The team’s aircraft were grounded by freezing fog and freezing rain for a few days, and team members are still finishing their surveys of all packs in the state.

Data from survey counts, camera footage and reported sightings will be compiled into an annual wolf report that will be released in mid-April, said WDFW statewide wolf specialist Ben Maletzke.

When Columbia Insight spoke with Maletzke on Feb. 14, the team had one more flight to do and some cameras to check, but they hadn’t yet been able to pick up the Big Muddy female wolf.

“We have not been super successful at finding that wolf, but that doesn’t mean she’s not out there,” Maletzke said. It’s possible she is on a hunting foray, he said, or “she may be more camera-shy” than her collared mate.

Maletzke acknowledged there is a “lot of animosity toward wolves in certain areas,” but he said there is no evidence of foul play involving the Big Muddy female.

Staci Lehman, a spokesman for the department, said “the wolf world can be a rough one. It’s not unusual for a wolf to go on a temporary or permanent road trip to new territories or to run into trouble along the way.”

New model for species recovery

If Southwest Washington’s only known pack has split up or the female has died, that would be “a big loss for sure,” said Maletzke.

In the short term, the loss of one wolf may have an impact for the next year or so, he said, “but over the next two to five years, I think we’ll see an influx of wolves down into the South Cascades.”

Maletzke said the state documented a lot of wolf mortalities in 2023 but is still seeing the species recovering in Washington.

The statewide population of wolves and the number of breeding pairs has been increasing for 14 years.

In its Periodic Status Review for the Gray Wolf dated February 2024, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife recommends that the state reclassify wolves from “endangered” to “sensitive,” bypassing the intermediate designation of “threatened.”

The agency says wolves no longer face a serious risk of extinction throughout a significant portion of their range in Washington.

The Wolf Management and Recovery Plan adopted in 2011 calls for the state to consider downlisting wolves from endangered to threatened when there are at least two successful breeding pairs in each of the three recovery regions for three consecutive years.

But that hasn’t happened yet.

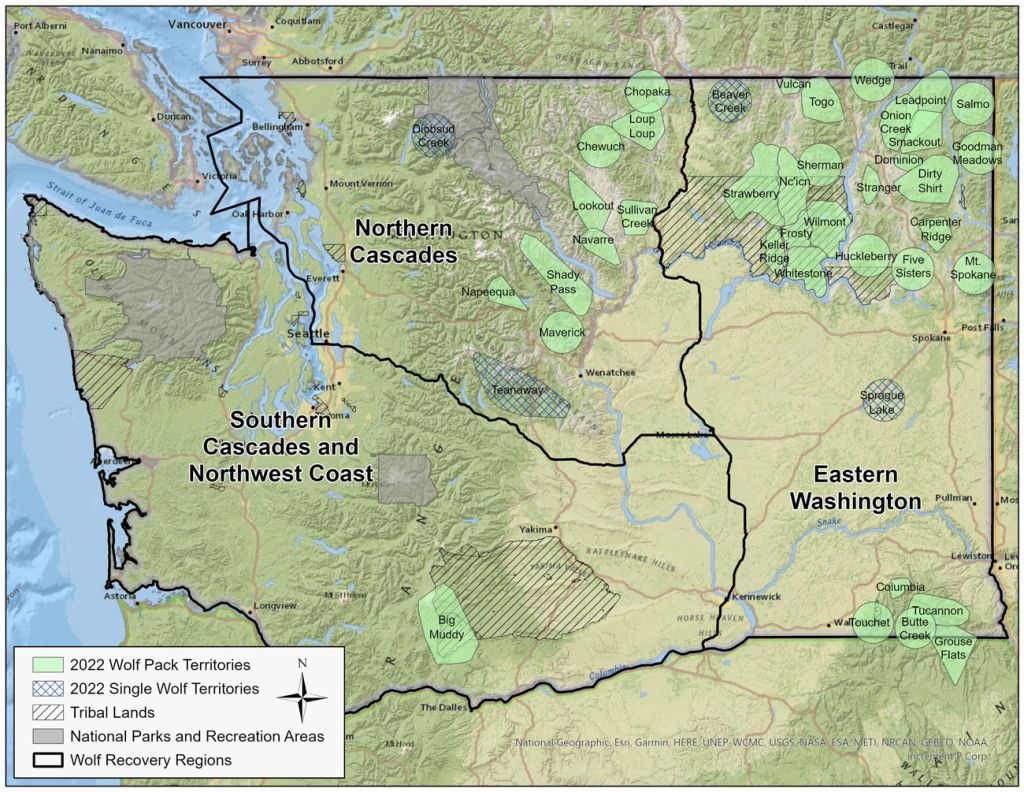

Known wolf packs and single wolf territories in Washington at the end of 2022. Map: WDFW

The Southern Cascades and Northwest Coast recovery region currently has no successful breeding pairs and, with the absence of wolf WA109M’s partner, might have lost its only known pair.

However, the state is proposing to jettison those recovery criteria and rely instead on a new model that estimates current and future population dynamics of Washington wolves.

The model estimates a 100% probability that wolves will “colonize” the southwest recovery region by 2030—meaning at least one wolf territory with two or more adults in it.

The downlisting proposal will be presented to the state’s Fish and Wildlife Commission at a meeting next month, and a decision is expected in June.

Both the draft proposal and the final version published this month note that “the first known pack was documented in [the southwest] region as of 2022.”

For now, that “pack” appears incomplete.

Dawn, thank you very much for this story. Why is WDFW so eager to jump the gun on downlisting wolves to “sensitive” when two-thirds of the state has no packs (if Big Muddy female gone), & has been much slower to colonize than NE WA and the N Cascades which are lightly populated and adjacent to the vast wilds of Canada? The model WDFW is using is not a good one because it fails to account realistically for significantly higher human impacts on the rate of colonization in the western two-thirds of the state; nor for how much worse this will be if they are downlisted. I hope people will contact the Fish and Wildlife Commission to ask them NOT to downlist wolves yet. Our ecosystems need all the help they can get, and the positive impacts of wolves on ecosystem health is well-documented in Yellowstone & elsewhere.

The state defines an endangered species as one that is “seriously threatened with extinction throughout all or a significant portion of its range within the state,” and a threatened species as one that is “likely to become an endangered species within the foreseeable future throughout a significant portion of its range.” WDFW says neither of those is a good fit for the current status of wolves in Washington, where the population is growing and spreading to new areas. WDFW says the best fit now is “sensitive” status, which means the species is “vulnerable or declining and is likely to become endangered or threatened in a significant portion of its range within the state without cooperative management or removal of threats.” This earlier story has more details about the agency’s reasons for recommending downlisting: https://columbiainsight.org/washington-wildlife-agency-recommends-relaxed-protections-for-wolves/

Dawn my son and I found what I believe is a wolf and it’s female. Could you please call me I want to have a biologist look at her. She took a liking to my nine year old son and she is really vocal and skiddish of people she threatens to bite every time someone touches her if they show fear at all they get bit. I don’t want my boy to lose his friend what should we do?

Wolves remain extirpated in 2/3 of their range in WA. I’d call that being seriously threatened with extinction in a significant portion of their range, where recolonization has proved difficult for them. Downlisting them will adversely impact their ability to recolonize. Folks, please write and ask Commissioners not to downlist them.