As drought conditions worsen, the state’s legislature is betting that an old technology will be able to turn some new tricks

Wishing on a cloud: Pilots from North Dakota-based Weather Modification, Inc. prepare a cloud-seeding aircraft with seeding flares. Photo: Derek Blestrud/Idaho Power

By Jordan Rane, March 31, 2022. “If you don’t like the weather in Idaho, just wait a minute and it’ll change.” Cue droll rim shot.

That’s the opening line of a four-minute promotional video called Harvesting the Storm produced in 2012 for electric utility Idaho Power.

With images of clouds sailing over sun-splashed mountains and a dated synthesizer score, the video starts off like a 1980s high school science-class film.

Rather than shutting eyes, however, the narrator’s next line opens them: “Only Mother Nature can change the weather—but we can modify it a bit through cloud seeding.”

Stimulating precipitation (snowflakes) by introducing a foreign substance (silver iodide) into clouds to (as Idaho Power’s video benignly puts it) “give Mother Nature a little boost” may sound like the latest advance in humankind’s eternal quest to control its environment. In fact, it’s been going on since the Truman administration.

MORE: So long, skiing? Study says Cascades could have no snowpack in 50 years

More than 50 countries currently have active cloud-seeding programs, according to the World Meteorological Association, coaxing a range of weather modifications from suppressing fog, frost, hail and heat to stimulating rain and snow.

In Idaho and other western states, such as Utah, Colorado and Wyoming, operational winter cloud-seeding programs aimed at amping snowfall (and spring melt) have been active for decades.

But recent state legislation supporting its use means you’ve probably been hearing more about cloud seeding lately than ever before.

With much of the West and practically all of Idaho facing severe drought, cloud seeding is “undergoing a small renaissance,” according to the Washington Post.

Legislative action

Idaho Power operates 26 cloud-seeding generators and serves more than half a million customers in southern Idaho and eastern Oregon. The utility says its cloud-seeding program produces a million acre-feet of water annually, or enough energy to supply nearly 60,000 homes.

Its argument has been convincing in many quarters.

Passed by the Idaho State Legislature and signed into law in 2021, House Bill 266 promotes more cloud-seeding opportunities as a “unique and innovative opportunity to augment and sustain the water resources of the state.”

“Cloud seeding is in the public interest,” states the bill.

Back on earth: Utah Gov. Spencer Cox said 2021 “could be the worst drought year on record.” Over 90% of the state experienced extreme or exceptional drought. Photo: Utah Division of Wildlife Resources

Although it doesn’t attach funding to cloud-seeding programs, the law does call for the expansion of programs, saying, “State funds may be used or expended on cloud seeding programs.”

The law is the broadest recent example of gathering support for increasing cloud-seeding efforts in the drought-stricken Columbia River Basin.

While it attracts questions about its efficacy (see below, “Does cloud seeding work?”), Idaho’s cloud-seeding “renaissance” appears to be bolstered by new numbers. In a good year, says the Idaho Water Resource Board, cloud-seeded basins have seen water increases as high as 15%.

Programs in other Western states suggest a regional trend. These include a joint effort to install ground-based, cloud-seeding generators in Wyoming-Colorado’s vast North Platte River Basin, where dual cloud-seeding programs have been undertaken over the last two winters by aircraft.

“I definitely think it’s one of those things that we can’t ignore, as far as drought mitigation,” Wyoming’s cloud-seeding program manager Julie Gondzar recently told the Idaho Statesman, while saying that cloud seeding, at its best, increases snowpack over time “slowly and incrementally.”

‘Teaching clouds’ to make snow

Cloud seeding’s origins date to 1946 when scientists discovered that injecting tiny particles of silver iodide into clouds could create additional precipitation.

Clouds that contain large quantities of “super-cooled” water that exist in a liquid state slightly below the freezing point are cold enough to produce snow.

If they don’t, explains Idaho Power’s senior atmospheric scientist Derek Blestrud, it’s because they’re lacking the nuclei to crystallize.

“For a snowflake to happen, crystals have to form around something,” says Blestrud (in the aforementioned video). “Otherwise most winter storms are inefficient, with water vapor transitioning downwind and not producing snowfall on the ground. So we add silver iodide to teach the cloud how to form snow.”

In seeded clouds, the inorganic chemical compound provides nuclei—tiny cores—on which water can condense to form water droplets or ice crystals.

The result: snowfall in as few as 20 minutes after silver iodide is released into the clouds.

How clouds are seeded

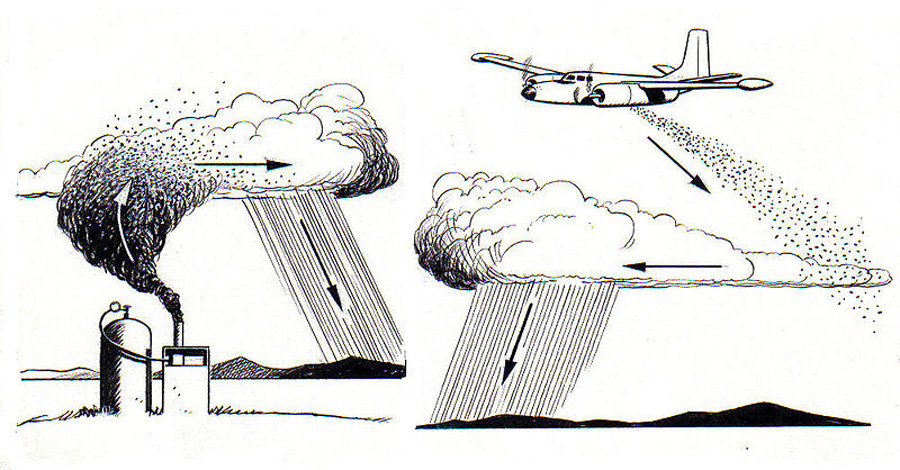

How does the silver iodide get into clouds? There are two primary methods.

Idaho Power propels its snow-making agent into the sky in winter and spring from ground-based towers erected in the mountains.

Stormbringer: Brandal Glenn of Idaho Power explains how a two-person crew can set up a remote, free-standing cloud-seeding tower in two to three hours. Screen grab: Harvesting the Storm/Idaho Power

The utility also releases flares from small aircraft. These flares send plumes of silver iodide above cloud cover, coaxing additional snowfall over the mountains.

In spring, the boosted snowmelt can irrigate fields and replenish reservoirs behind hydroelectric dams, eventually generating additional megawatt hours of hydropower.

The Idaho Water Resource Board provides funding for state water projects, including Idaho Power’s cloud-seeding programs in the Boise, Wood and Upper Snake River basins.

It’s considering more cloud-seeding projects for the southeastern part of the state.

Is cloud seeding safe?

Safety is one of the first things people ask about cloud seeding.

Scientists and other experts tend to brush aside the concern.

Pump It Up: Cloud-seeding machine. Photo: DRI Science

“It’s a common misconception that silver iodide is harmful,” says Sarah Tessendorf, a cloud physicist at the National Center for Atmospheric Research in a recent Washington Post article. “Silver iodide occurs naturally and cloud seeding injects amounts smaller than we can detect. … Snow and water sampling shows that silver from cloud seeding is well below other sources like natural mineral dusts and very far below EPA regulations.”

According to Encyclopedia.com, in cloud-seeding operations “only small amounts of silver iodide are released into the atmosphere. That which does fall to earth does not dissolve in water and so is unlikely to enter a community water supply. Tests have shown that the concentration of silver iodide in rainwater is far below the 50 micrograms per liter that has been deemed safe by the U.S. Public Health Service.”

However, not all scientists agree cloud seeding is harmless.

A 2016 study published by the National Library of Medicine found “cloud seeding may moderately affect biota living in both terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems if cloud seeding is repeatedly applied in a specific area and large amounts of seeding materials accumulate in the environment.”

“The silver ion is among the most toxic of heavy metal ions, particularly to microorganisms and to fish,” according to research first published in 1970 in the journal Water Resources Research. “The ease with which (it) forms insoluble compounds, however, reduces its importance as an environmental contaminant.”

The National Library of Medicine rates silver iodide as an environmental hazard, calling it “very toxic to aquatic life.”

Does cloud seeding work?

This is where cloud seeding becomes more controversial.

Cloud seeding was developed in the 1940s by an American chemist named Vincent Schaefer while working at the General Electric Research Laboratory in Schenectady, New York.

In his first experiments, Schaefer dropped crushed dry ice from an airplane into cloud formations. He reported success, with rain or snowstorms resulting from this seeding.

Work in progress: Silver iodide particles are distributed on clouds through aircraft or from ground-based generators to produce artificial rain. Illustration: Wikimedia Commons

Throughout the rest of the 20th century scientists attempted to validate and improve upon Schaefer’s work, with mixed results. In the late 1970s, the United States invested more than $20 million a year in weather-modification research, but by 2003 it was spending less than $500,000 annually.

In 2003, the National Academy of Sciences issued a report stating that no reliable scientific evidence existed to suggest cloud seeding produced more rain or snow than would naturally occur.

“There is ample evidence that ‘seeding’ a cloud with a chemical agent—such as silver iodide, which could form ice crystals that may fall as rain—can modify the cloud’s development and precipitation,” wrote The National Academies of Sciences in 2003. “However, scientists are still unable to confirm that these induced changes result in verifiable, repeatable changes in rainfall, hail fall and snowfall on the ground.”

As drought in the West becomes increasingly dire, however, community and state leaders are becoming more desperate for solutions.

Proponents of cloud seeding say the problem isn’t necessarily that cloud seeding doesn’t work. Simply that it’s difficult to prove that it does.

One of the toughest things to divine is how much precipitation a cloud might have dropped naturally prior to being seeded. There’s simply no way to know that.

Tempered optimism

“We’re using new models to evaluate the impact of cloud seeding, and we have observed direct evidence of the pattern of snow produced by cloud seeding—but we still have more questions,” says Tessendorf of the National Center for Atmospheric Research, adding that most statistical programs comparing the amount of precipitation from randomly seeded clouds to unseeded ones have failed to meet statistical significance. “The signal from cloud seeding is often very small and within the range of natural variability.”

“We can add snowpack to equip our reservoirs for a drought and build supply for when we need it,” says Idaho Power’s Blestrud with the same measured optimism, “but we cannot use cloud seeding to fix a drought.”

Get new Columbia Insight stories every week—free here.

The language in Idaho House Bill 266 echoes that mix of optimism and equivocation.

“Data accumulated and analysis undertaken demonstrates that cloud seeding has resulted in an annual increase in water supplies in the basins in which it has been performed,” states the bill. Then comes the caveat: “Additional research and analysis is necessary to determine the precise nature and extent of those increases.”

Don’t like the results of cloud seeding? Wait a few minutes its advocates seem to be saying. Something is bound to change.

Columbia Insight contributing editor Jordan Rane is an award-winning journalist whose work has appeared in CNN.com, Outside, Men’s Journal and the Los Angeles Times.