A compelling documentary lays out the case for breaching four dams on the lower Snake River, saving Idaho salmon and exposing power politics. We asked the team that made it to explain

Sea change: Resident killer whales in the Salish Sea rely on chinook salmon from the Columbia Snake River system for survival. This young resident was photographed pursuing a chinook meal in 2017. Both populations are dwindling. Photo by John Durban/NOAA Fisheries

By Chuck Thompson. August 27, 2020. The documentary Dammed to Extinction ties four dams located on the lower Snake River to the looming extinction of the Southern Resident orca population in the Salish Sea, often found in Puget Sound and around the San Juan Islands in Washington. The film draws a clear line from the dams—all are located in Washington—to the decimation of chinook salmon populations, upon which the killer whales depend for survival.

The centerpiece of the argument to remove the dams is that, largely due to the emergence of wind and solar power, the dams are now money losers that have become hydroelectric redundancies on the larger power system. It’s an emotional, articulate and urgent call to breach the lower Snake River dams in order to save orcas, salmon and an entire wild eco-system in Idaho.

Produced in 2019, the film’s 2020 festival and publicity schedule was derailed by the COVID-19 pandemic. A must-watch that leaves audiences sad, angry, stunned and inspired, it’s available for purchase at the Dammed to Extinction official website.

Not everyone agrees with the film’s conclusions.

On July 31, a federal government coalition co-led by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (which built the dams in the 1960s and ’70s), Bonneville Power Administration (which markets power from the dams) and U.S. Bureau of Reclamation released a long-awaited court-ordered Environmental Impact Statement on the dams. It rejected calls to breach the dams.

“While the Preferred Alternative does not include breaching of the lower Snake River dams, it calls for actions that are substantially different from those that have been implemented in the past,” reads the EIS executive summary. These changes include “a flexible spill operation that spills more for fish passage when power generation is less valuable and spills less when power generation is more valuable.”

On August 13, Columbia Insight’s Board of Directors met via Zoom with Dammed to Extinction filmmakers, writer Steven Hawley and producer Michael Peterson, to discuss their documentary, the recent government decision and the future of power in the Columbia River Basin. The following is an edited transcript of that conversation.

Dammed intermission: The film’s release has been hampered by COVID-19.

Columbia Insight: In July, a coalition of federal agencies issued a report stating the four lower Snake River dams will stay in place. Does the finality of that decision have a bearing on how people opposed to the dams might proceed?

Steven Hawley: We now have a cabal of federal agencies that over the past 20 years has spent $100 million finding out that the best way to restore salmon is to remove the lower Snake River dams. For our $100 million in both of those studies—one cost $30 million, one cost $70 million—they chose not to go with the best option. They didn’t follow their best information. So the question becomes why didn’t they?

It used to be that there was a lot of money in the business model that Bonneville was running. But the reality as we (document) in our film is they’re going broke. So it’s just again bad governance, poor leadership and a desperate clinging to the status quo.

CI: The Corps of Engineers says the dams are staying. But Bonneville is losing money. How does Bonneville feel about this decision?

SH: There’s a joke in the region that all the federal agencies speak with one voice: Bonneville’s. You have to remember that a lot of the work that the Corps does is funded through Bonneville.

The Corps of Engineers, although they contributed to the Environmental Impact Statement, the agency that signs off on both the EIS and the biological opinion is NOAA, the National Marine Fisheries Service [an agency within NOAA]. The interesting thing about that Seattle office of NOAA is it is in fact funded two-thirds by both the Corps of Engineers and Bonneville. This is complicated and confusing because NOAA is supposed to be this independent arbitrator of whether or not those agencies are doing the right thing on the river. … Well, if you’re paying the guys that are trying to figure that out, or provided two-thirds of their budget, it kind of skews the potential outcome in your favor, right?

CI: But if their own people are telling them they’re losing money, what’s Bonneville’s interest in keeping the dams in place?

SH: This time around they’re making the argument that we can’t get rid of these carbon-free sources of power. That’s not true because it’s been well established by science over the past 15 years that every reservoir on earth emits massive amounts of greenhouse gas in the form of methane. There’s a study done in 2016 and updated in 2018, and it was just two reservoirs out of the main eight on the Columbia River and Snake, and it was determined those two reservoirs emit the same amount of greenhouse gas equivalence as a 165-megawatt, gas-fired turbine facility in western Washington.

Nobody has ever studied how much methane is actually released by the entire system. I think if that were studied the movement to get rid of the dams would accelerate. Water spinning a turbine in fact releases lots of methane. … If somebody (wrote) that story … it would change the nature of the discussion about salmon recovery as well as energy.

CI: Elliot Mainzer is departing this month as top administrator at BPA. What does that mean for the future of the Snake River dams or the movement to oppose them?

SH: You have to remember that Elliot Mainzer started out as a floor trader for Enron 20 years ago. And he probably has a pretty good eye for disaster when it’s coming. Bonneville is in a lot of trouble financially and I think he didn’t want to stick around to be on the ship when it sinks.

The other question is, who comes next? I have some ideas and they’re all going to be less friendly faces than Elliot, which could possibly work in our favor as far as a campaign to get the dams removed. Elliot was the kind of politician that could smile and shake your hand and stab you in the back at the same time. Maybe somebody who’s a little less adept at that would leave some potential avenues for dam removal.

CI: Some regional politicians get up in Congress making statements about historically large chinook runs and other assertions that are at odds with the facts. What’s motivating those Members of Congress to make those kinds of statements that can be so easily refuted?

Script doc: Steven Hawley also wrote Recovering a Lost River, which inspired the 2014 documentary Dam Nation. Courtesy of Peterson Hawley Productions

SH: One thing we didn’t have the room to include in the film is what a powerful lobbying organization those federal agencies and their constituents are in Washington, D.C. The Corps of Engineers, Bonneville, the Bureau of Reclamation are routinely wandering the halls of Congress meeting with congress people, meeting with the heads of committees that can fund their work.

They’re too big for anybody in this region to challenge. And they’re too small back in D.C. for anyone to really care. … There’s a lot of institutional inertia in that arrangement and it’s going to take a lot of persistent effort to undo it.

Michael Peterson: As far as the politicians, I think some of the most egregious are Cathy McMorris Rogers, obviously, and Dan Newhouse. [Both are U.S. representatives from Washington.] For the most part they’re representing their constituents. I grew up in eastern Washington. I grew up next to those dams. If you look at it from an outsider’s perspective, it’s like, “These don’t make sense. Let’s get rid of these things.” I know people that work there. People are very proud of these dams. They think they’re doing a great thing. They think they’re producing renewable energy that’s helping power the world and provide transportation and barging for agriculture and a little bit of irrigation.

So, as far as Dan Newhouse’s position or Cathy McMorris Rogers’ position, they are going to represent the people of their district. … Obviously a politician is going to twist the facts so that they represent what their point is and what they want to get across.

CI: The data industry that’s using cheap power to build their plants in our small towns is able to negotiate things like not paying property taxes because they’re presumably doing such a good thing for the communities. [In 2018, Wasco County estimated Google’s property tax breaks to be worth almost $140 million since 2006.] In The Dalles, Google has $1.8 billion worth of investment [as of 2018]. Are Amazon and Google at all a player in this?

SH: They’re using the same amount of electricity there at the Google factory in The Dalles as the City of Tacoma. … It’s hard to convince a corporation to do the right thing just for the sake of doing the right thing. But what they will look at is their bottom line. And the reality is it’s not the cheapest game in town anymore to buy power from the Bonneville Power Administration, even if you can get a sweetheart deal like the one Google got.

The profound shift in energy markets that you heard the economist in our film describing, Tony Jones, that’s only gotten worse since we finished making our movie. Tony talks about how prices occasionally go negative in the midday in California because there’s so much solar on the market now. I got a note from Tony in July and he pointed out there were a few hours in a day in July when the price for energy on that day-ahead spot market went to minus-$45 per megawatt-hour. So that means producers were paying consumers to use power. They were paying them $45 a megawatt-hour just to take the power.

CI: With so much wind and solar energy coming onto the market, can the existing power-business model be sustained?

SH: This is a much bigger story than just the Snake River dams. I think it’s quite possible that within the next 20 years the whole model of the way we deliver electricity—these large, aging, centralized generators and this far-flung transmission system—could be completely out the window. The interesting thing about this will be the politics, because as we’ve already brought up there’s so much political power and institutional inertia in the current system that it’s going to be difficult to change. But the numbers are on our side. It’ll be interesting to see what Google and Facebook do when their sweetheart contracts expire.

CI: Are we hearing you say the real story is about a new power paradigm that offers hope for radical change?

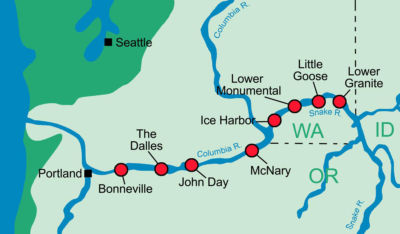

Concrete positions: Starting with Ice Harbor dam and moving east (red dots indicate dams), environmentalists want four Snake River dams breached. The federal government has issued a hard no. Courtesy of U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

SH: We are so confident that is the next chapter of this story that we’re hoping to start filming a documentary about that very topic. About renewable energy and the hope it provides.

MP: The people that own these dams, the government, they’re not going to do the right thing. We’ve decimated an entire eco-system from Idaho all the way up to Seattle and Vancouver and Canada. We destroyed it. We’ve ruined salmon runs. We’ve affected all the different species. We’ve got problems with lamprey. We’ve got problems with seals, with orcas. And these dams are responsible for it and now they’re losing money and they still want to keep them. So the point is, the right thing is not going to be done for the environment. It’s going have to come down to money. … It’s going to have to be something like a change in the power grid.

CI: Even with advances in a new power system, is it too late for the orcas?

MP: It’s a hard question and the answer is as long as there are orcas swimming we’re going to keep trying. I see the Southern Residents dwindling and I’m not sure they’re going to make it. However, as long as there are at least two of them out there I have some hope.

CI: What about a political regime change this fall?

SH: Unfortunately, it doesn’t seem to matter who’s in the White House. You can always rely on Bonneville Power and its sister agencies producing just really rotten leadership. It doesn’t matter if it’s a Democrat or Republican in office.

The arguments this time around have gotten ridiculous. These people definitely feel emboldened when they have a friend in the White House. One quick example, they’re claiming the replacement cost for the power alone for the four lower Snake River dams would be $400 million a year. Those dams produce electricity four months out of the year in the springtime when there’s so much electricity on the western power grid that people are giving it away. So where they come up with $400 million to replace power that no one wants to buy is another question.

CI: Is a short-term fix as simple as taking out the doors on the locks and letting that water run through?

Big fish: Producer Michael Peterson’s visual effects film credits include Independence Day, Armageddon and Star Trek First Contact. Courtesy of Peterson Hawley Productions

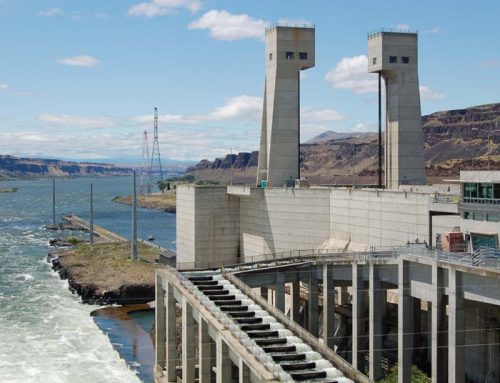

MP: If you look at an aerial photo of these dams you’ll notice almost all of them have an earthen berm to the side. They were actually built to be temporary and to be removed. They don’t even need to remove the concrete. They could just remove the earthen berm on the side and you will have a free-flowing river around the side. It’s really not very hard.

CI: How does your film fit into a larger strategy of getting these dams removed? Is there a group in charge of a campaign to remove the Snake River dams?

MP: If there’s any big problem, that’s it. There are a lot of very passionate groups on both sides of the Cascades that have been really trying to get these things done. Unfortunately they’re split into factions. So there is no really one unifying voice. … There isn’t a cohesive movement. It would benefit from that for sure if we could get everybody on the same page.

As far as how our film fits into it, the power of film is pretty great. And the thousands of people that this film has reached already has I’m sure changed a lot of opinions and generated a lot of interest. So, it’s a tool that we’re happy to let anybody use.

CI: In addition to simply killing a lot young salmon as they migrate to the ocean, dams also delay their migration. Can you explain the problem with that?

SH: There is a concept called “differential delayed mortality,” which says that particularly for the young ones migrating out from higher up in the system every dam they have to pass saps essentials for everything they need not only to make it to the estuary, but there’s an incredible transformation that takes place from becoming a freshwater creature to a saltwater creature. If it takes them too long to get from the Middle Fork Salmon in Idaho to Astoria, they simply don’t have the energy to make that change. They won’t go out into the ocean.

CI: Why are the four Snake River dams more problematic than the four dams on the lower Columbia, which would still obstruct fish passage even if the four Snake dams were breached?

SH: You have to remember the grand prize here is providing unfettered access to all of that wild country above the last dam on the Snake River. You’re talking about 5,000 linear miles of creeks, rivers and streams that once produced half of all the salmon in the Columbia. You’re looking at roughly 2.5 million salmon every year in the pre-dam era. So, that’s the prize. We may not ever get back to that, at least not in any kind of human timeline. But the potential is there.

On the Middle Fork Salmon River in Idaho there’s a tattered map of the mainstem and a few tributaries showing exactly three salmon spawning areas in the whole Middle Fork Salmon drainage. This is a river in the middle of 4.5 million acres of wilderness in Idaho and a little bit in eastern Oregon and Washington that used to produce hundreds of thousands of salmon every year. In 2019, we were down to three spawning areas in the entire drainage area.

The documentary I don’t want to make is following a couple iconic species like this into extinction. After kicking the can down the road for so many years, it’s final exam time on this issue. At this point it’s not clear to me whether we’re going to pass. But we have to try. That’s why we made the movie.

Chuck Thompson is the editor of Columbia Insight. Columbia Insight‘s series focusing on the Lower Snake River dams is supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Where can I find the study about dams releasing

GHG. Methane etc. 2018.

Hi Joan: I’ve reached out to the filmmakers with this question. Stand by.