A new study also says climate change is making it harder to escape drought even as winters bring lots of precipitation

Can’t get enough: Rylee Buckley, 17, fills a water container with a neighbor’s hose in July 2021, in Klamath Falls, Ore. The Buckley’s house well ran dry following an historic drought in southern Oregon. File photo: AP Photo/Nathan Howard

By Nathan Gilles. November 27, 2024. Last week, Oregon, Washington and California got hit with a “bomb cyclone” and atmospheric river that drenched the region, killing two and leaving hundreds of thousands without power.

This came just two weeks after an early season snowstorm pounded Colorado and New Mexico, dumping so much snow that some cities saw more from this one storm than they typically receive in a year.

With two impressive precipitation events hitting the western United States back to back, it’s easy to forget that drought has been a near constant in the region for decades.

Despite heavy snowfall, the American Southwest is still in the midst of its worse “megadrought” in over 1,000 years. Despite intense winter storms, since 2007 California has consistently experienced a trend of multiple back-to-back drought years with only a handful of wet years as respite.

Even the currently soggy Pacific Northwest has spent more of the last decade in drought than out of it.

How can this be? And will these intense winter precipitation events ever be enough to get the West out of drought?

A recent paper in the journal Communications Earth & Environment gets us closer to answering these questions.

Traditional drought-prediction tools are becoming obsolete as climate activity becomes more unstable.

The study is the first to put numbers to what many scientists and water managers have long suspected—it’s becoming increasing difficult for states in the western U.S. to recover from drought as climate change accelerates. This is true despite the fact that winter precipitation events are becoming more intense, a phenomenon also likely due to climate change.

The study estimates that during the first two decades of this century, the probability of drought recovery dropped by 25–50% across the western U.S. when compared to drought recovery that occurred during the first eight decades of the 20th century.

The reason for the declining likelihood of recovery, according to the study, is that many parts of the West have been running multi-year water deficits.

These deficits are due not so much to lack of precipitation—although this is a factor in some areas—but to rising temperatures that are causing water to evaporate before it can be stored in the soil to be used by people and ecosystems alike.

Water recovery slowing

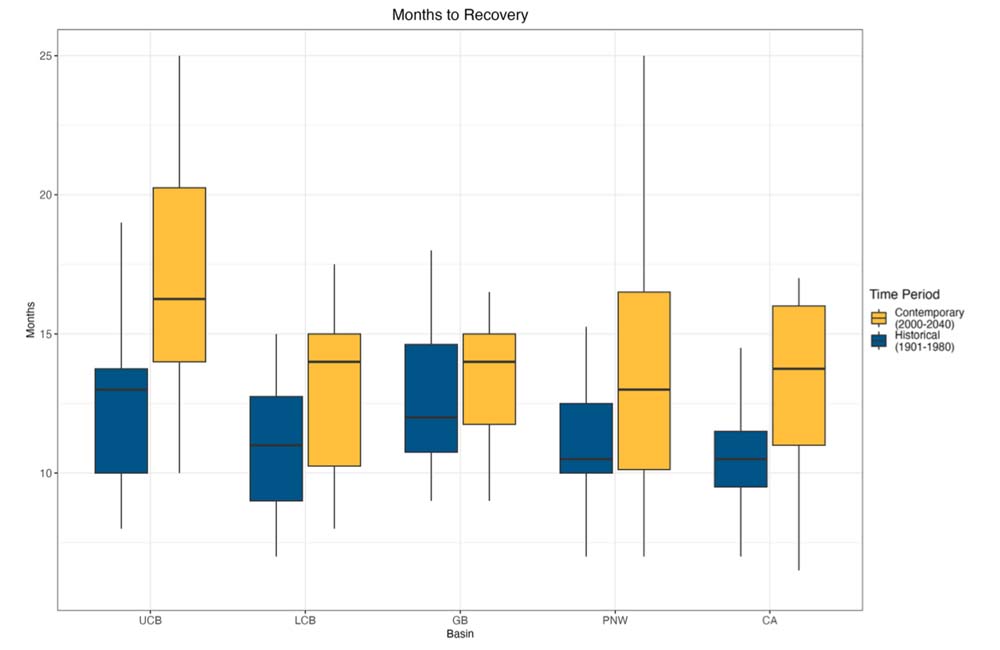

It’s now taking the western U.S. approximately one to four months longer to recover from drought than it did in the recent past. This trend is likely to continue as climate change accelerates, according to the study.

“One to four months, maybe that doesn’t sound like a lot,” says study lead author Emily Williams, a postdoctoral scientist at the University of California, Merced. “But when you actually think about when you’re in a drought deficit, when day zero-water is looking more and more likely, when water supplies are falling, an additional one to four months to get out of a drought can make a really big difference.”

To determine the likelihood of drought recovery in the West, Williams and her coauthors break the region into five areas based on river basins. These are the Upper Colorado Basin, Lower Colorado Basin, Great Basin, California and Pacific Northwest, which tracks the Columbia River Basin and includes parts of Oregon, Washington, Idaho and western Montana.

Recovery time for water supplies is getting longer in the Upper Colorado Basin, Lower Colorado Basin, Great Basin, Pacific Northwest and California. Source: U.S. Drought Monitor

The researchers examined monthly drought-severity observations collected across the U.S. West from 1901 to 1980 and compared these to monthly data collected from 2000 to 2021.

Then they compared these historical data to data derived from models that ran simulations of the climate over the same time periods. This included a so-called “counterfactual” analysis that used simulations of the region’s past and current climate that didn’t include human-caused climate change as a factor.

The analysis revealed that in recent decades all five western regions have not only been drier than they were during the 20th century, but they were also drier than the counterfactual simulations predicted they would be had climate change not occurred.

Crunching the numbers further, the researchers concluded that at least one-third of the reduction in drought recovery in recent decades can be directly attributed to human-influenced climate change.

The study’s last finding adds the paper to a growing body of similar attribution studies linking drought in the West to carbon pollution.

Running up the water deficit

Perhaps the study’s most significant finding came when Williams and colleagues broke down the region’s “drought recovery probabilities” on a season-by-season basis.

They found that drought recovery probabilities in some regions increased in recent decades. These gains, however, occurred only during the region’s wet winter months.

During spring, summer and fall, the opposite occurred: drought recovery probabilities tended to decline.

This led the researchers to conclude that increased evaporative demand driven by abnormally warm temperatures during non-winter months was slowing drought recovery.

In other words, warming temperatures tied to climate change are making it too hot and consequently too dry during non-winter months for the West to hold onto its water supply from winter to winter and year to year.

Get it yet? Like Matt Lisignoli, whose Smith Rock Ranch is in the Central Oregon Irrigation District, farmers and ranchers are always antsy about water. More so in recent years. File photo: AP Photo/Nathan Howard

“The main takeaway from our study is that even if we do have these wetter winter storms that dump a lot more precipitation, it’s just not enough to make up for that deficit in the warmer months,” says Williams.

To visualize this, study coauthor John Abatzoglou, professor of climatology at UC Merced, says it helps to think of water supply and demand like deposits and withdrawals in a bank account.

During winter months, water gets deposited in the bank account as rain and snow.

During the spring, summer and fall months that follow, water gets withdrawn as warming temperatures dry out soils.

When demand exceeds supply, drought occurs. Getting out of drought debt means both satisfying current water demand and making up for past water deficits.

Periodic droughts aside, the seasonal ebb and flow of water supply and demand has long been a stable feature of the American West. It’s a feature that both ecosystems and people have come to rely on. The warmer, drier months are when both tend to withdraw the largest amounts of water from the bank.

The problem, says Abatzoglou, is that, due to climate change, the West’s climate is no longer stable.

Extending the analogy further to one likely to resonant with many Americans, Abatzoglou says climate change and the drying effect it creates acts like inflation or a tax that puts further restraints on water demand.

“With climate change and winter, especially in much of the West, things might be a little better [in terms of water supply],” says Abatzoglou. “But the question is, can we make up for the continual strain, that inflation or tax, on our system due to warmer drier conditions in the dry season, which is adding to the demand side.”

The study, it would seem, answers this question mostly in the negative. Many parts of the West have consistently experienced multi-year water deficits, in part because the region now needs larger amounts of precipitation to overcome evaporative demand.

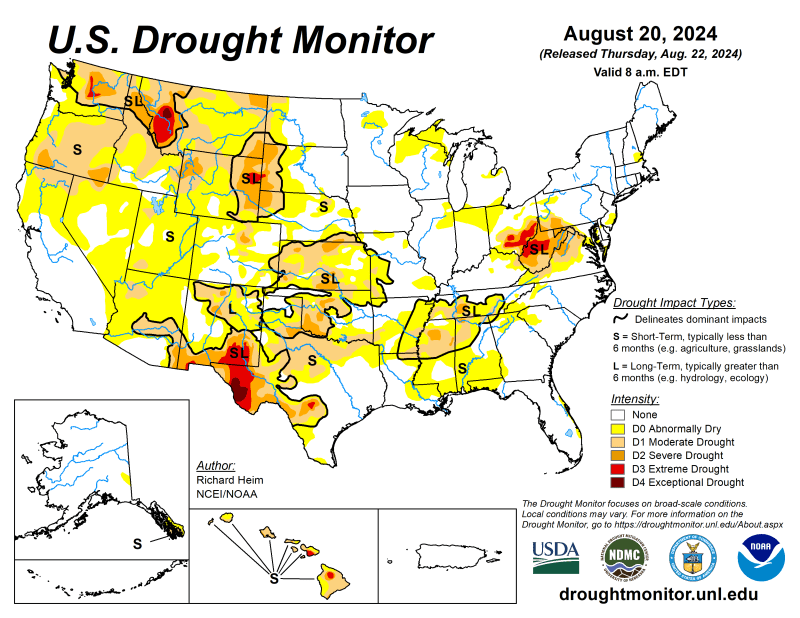

Familiar pattern: By mid-summer of this year, most of the Pacific Northwest, and western U.S., was experiencing drought or abnormally dry condition. Map: U.S. Drought Monitor

Larry O’Neill, state climatologist of Oregon and associate professor at Oregon State University, who was not involved in the study, says the study’s findings are unlikely to surprise anyone in water resource management in Oregon.

“When we have a drought, it’s basically lasting longer and it’s less predictable for how we can get out of it,” says O’Neill.

As part of his duties as state climatologist, O’Neill sits on the Oregon Water Supply Availability Committee and the Drought Readiness Council.

The committee and council advise the Oregon governor and legislature on droughts and their impacts, and advises the governor on drought declarations.

The 22-year period running from 2000 to 2021 is estimated to be the driest period on record in Oregon in the past 1,200 years, according to the State of Oregon.

Echoing the study’s findings, O’Neill says a major driver of the state’s recent droughts has been abnormally warm temperatures, something he says was apparent during the drought that occurred from 2020 to 2022.

“That drought was just so severe,” says O’Neill. “It took longer [to recover] especially in central Oregon. And the big reason was because there was just so much evaporation from the landscape that it was just sucking every last drop of water out.”

Ultimately, Williams and Abatzoglou say they’d like to see their research applied to the real-world problem of drought recovery prediction as climate change worsens, noting that colleagues at the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, which oversees several drought prediction and monitoring efforts, have expressed interest in their work.

“It’s now taking longer to get out of drought, and that trend is projected to continue,” says Williams.