Getting the River Democracy Act to Congress took hundreds of meetings, but also comfortable pants and more than a few pieces of blueberry pie

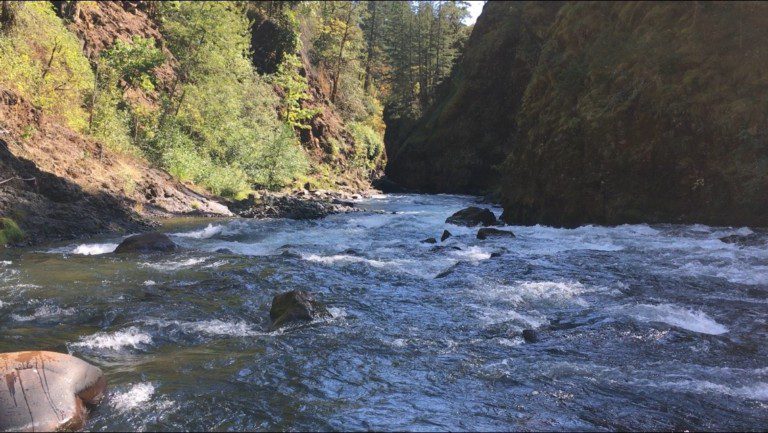

Click above to listen to an expanded version of this story on that latest edition of the Columbia Insight podcast. Host Isabelle Tavares shares the story behind the creation of the River Democracy Act. She speaks with the legislation’s co-sponsor, Oregon Sen. Ron Wyden, and others involved in the effort to protect thousands of miles of Oregon rivers and streams from development. Rogue River photo by Zach Krahmer

By Isabelle Tavares, May 13, 2021. In the early 1970s on the University of Oregon campus, a fatigued student closed his textbook, descended the stairs of the Oregon College of Law building and beelined toward a group of friends who beckoned from a car waiting outside.

He sandwiched into the backseat. As campus demands faded he began to relax and appreciate in the scenery. Pavement turned to dirt and highways turned to waterways. By the time the group arrived at their destination along the McKenzie River he was re-energized. The car doors couldn’t open fast enough.

Cloudy with a chance of groundbreaking legislation: Oregon Senator Ron Wyden. Photo by Office of Ron Wyden

The young man carried with him that day three things he appreciated about as much as anything—his friends, a fresh blueberry pie and a love for Oregon’s rivers.

Nearly half a century later that student would go on to craft a groundbreaking piece of federal legislation aimed at preserving the kind of experiences he’d enjoyed on his many river excursions as a young student.

MORE: New pressures threaten White Salmon River corridor

Now known across the state as Senator Ron Wyden, that former law student’s River Democracy Act (RDA)—introduced in the U.S. Senate in February by Wyden and co-sponsor Sen. Jeff Merkley, Oregon’s other Democratic senator—promises to protect and preserve 4,700 miles of Oregon rivers under the national Wild and Scenic Rivers system.

The proposed legislation shields rivers and streams from damming and development, while preserving clean drinking water and healthy habitat for fish and wildlife, and supporting a robust recreation economy.

Wyden’s earliest ideas for the act were inspired by afternoons spent with a fork in a blueberry pie and his feet in the McKenzie River.

“I just felt this was the right thing to do,” Wyden told Columbia Insight about the RDA. “We love our rivers, they’re so important for so many reasons, and (I thought) ‘I can try something that’s never been done before.’”

‘Very fun job’

For those familiar with Wyden’s long record of environmental protection, it wasn’t a question of if he wanted to preserve rivers, but which ones he’d want to include in his legislation. Wyden himself wasn’t sure.

To help make the decision, he put out a call to Oregonians asking for input. Over 2,500 responded.

Riding the current: Oregon Wild’s Jamie Dawson was part of the wave of support for the River Democracy Act. Photo courtesy of Oregon Wild

“When I started asking people about the idea of river democracy … all the papers said ‘Can’t be done, he’ll never do that,’” says Wyden.

An unprecedented public nomination process lasted from October 2019 to February 2020. Wyden appeared before packed halls from Astoria to Pendleton. With responses from elementary students to retirees, 15,000 suggestions for favorite rivers and streams flooded nomination boxes.

Over 970 town hall meetings later, Wyden says those conversations gave him “the spark.” It did the same for others.

“In environmental organizations, we can spend 10 years bugging senators (for help),” says Jamie Dawson, public lands campaigner at Oregon Wild (OW), a Portland-based environmental nonprofit. “But this, I swear, was a miracle when he came to us and said ‘Let’s do a river bill.’”

Dawson got the “very fun job” of promoting the measure during the five-month public nomination period. For her, numerous events stand out, including a film screening in Bend where people gathered Chaco-to-Chaco while OW distributed nomination cards.

“There was so much interest we were almost breaking fire code,” says Dawson.

Ditching ‘uncomfortable clothing’

So what exactly does the “democracy” part of the River Democracy Act refer to?

Community events, like all those town hall meetings, bring autonomy to constituents at a time when public lands legislation can feel inaccessible, explains Wyden.

MORE: Idaho Rep. Mike Simpson breaks down his plan to breach Snake River dams

“Environmental policy usually involves a bunch of people debating in Washington, D.C., sitting around in uncomfortable clothing,” he says, adding that the traditional avenue of protecting rivers has been “turned on its head” with this legislation.

The RDA includes numerous ideas that came out of those public meetings.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“There was so much interest we were almost breaking fire code.” —Oregon Wild’s Jamie Dawson[/perfectpullquote]

Existing Wild and Scenic Rivers provisions typically impose a quarter-mile corridor limiting development around protected rivers. The RDA expands this corridor to a half-mile on all protected rivers in the state in order to minimize wildfire risk. (Some Oregon rivers are already protected with a half-mile corridor.)

The bill also allows federal land managers, for the first time in many instances, to enter into cooperative agreements with local tribes, landowners and governments to co-manage river segments.

The Burns Paiute Tribe, for example, worked with Wyden to ensure native fish restoration could continue on Wild and Scenic River sections.

Gems in arid places

Signed in January to address the “profound climate crisis,” President Joe Biden’s “30 by 30” executive order seeks to protect 30% of U.S. land and 30% of U.S oceans by 2030.

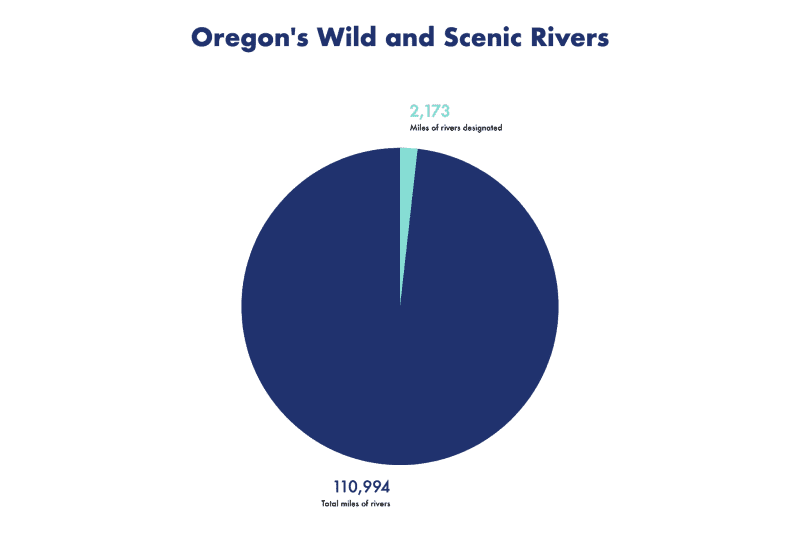

Wyden and others see the RDA as compatible with those goals. While 14% of Idaho’s land and a little less than 10% of Washington’s land is protected as wilderness, only 4% of Oregon’s wilderness is protected. Oregon currently has 2,173 miles designated in the Wild and Scenic Rivers system, but that total remains only a small fraction of the state’s 110,994 miles of rivers and streams.

In terms of protected wilderness, Oregon is at the “bottom of the barrel” according to Julie Weikel, a retired veterinarian in eastern Oregon. A longtime activist for animal welfare and environmental protection, Weikel was recruited to review a list of eastern Oregon waterways that had a shot at making Wyden’s final list.

Most people think of Oregon as a lush green landscape, and the state’s identity is linked to forests, Weikel says. But in the arid region east of the Cascades, where sagebrush spans the landscape, clear-running rivers and streams are the difference between “making it and not making it.”

“My grandmother raised her seven kids out of her three-acre garden watered by a mountain stream,” says Weikel. “That’s made me appreciate those precious little water gems out in the desert.”

Next steps

Introduced into Congress on February 3, the RDA is now in the early stages of what will likely be a lengthy legislative journey.

If passed by the Senate Energy and Natural Resources committee, where it currently resides, the bill will be sent to the House and Senate for debate, amendments and votes. Neither Wyden nor anyone else associated with the bill will venture a guess on when that might happen.

MORE: Climate change will exacerbate flooding in Columbia River Basin, OSU study finds

Wyden is patient. The RDA has been a long time in the making and, like his memories of more carefree days on the McKenzie, the state’s rivers aren’t going anywhere.

Time shapes generations in the way rivers shape landscapes. Many Oregonians have been shaped by the state’s rivers. Wyden knows that as well as anyone and his River Democracy Act aims to keep it that way.

Columbia Insight intern Isabelle Tavares is a journalism master’s student at the S.I. Newhouse School of Public Communications at Syracuse University.

To see a map of proposed rivers that would be protected by the RDA click here.

I believe the rivers in Central and eastern Oregon need to be managed by the population that live in the area and know the water supply and useage. To have a mile on each side of these water ways protected by an entity that is not even present will cause a cumbersome process to okay any useage change. Please give the natural resources back to the local people. City dwellers do not have the knowledge to be able to responsibly determine how these waterways should be managed. The era of cattlemen allowing their herds to damage stream banks is long over and they know best how to preserve fish, wildlife and water quality. Thank you for your time

In Central and Eastern Oregon, water quantity equates water quality. That in-stream quantity of water was completely appropriated more than 120 years ago, not to protect the resource, but to incentivize agricultural and commercial development of the desert west. The RDA can overlay protection of the river, but unless there is systematic change in western water law, those protections and the rivers themselves will be dry sand and stones where the wild and scenic heritage of Oregon used to be.