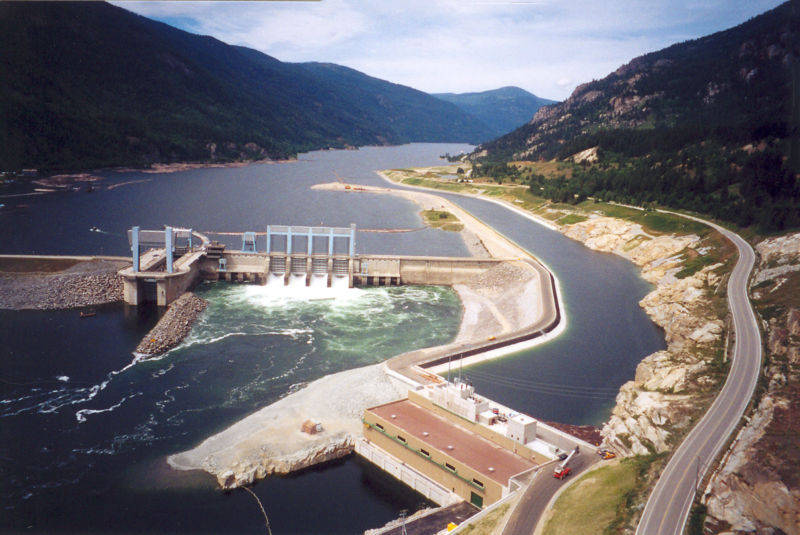

Not enough: B.C.’s Hugh Keenleyside Dam needs regulating. But so do a lot of other things. Photo courtesy Wikimedia Commons, DAR56

By Graeme Lee Rowlands. July 2, 2020. On June 30, the U.S. State Department and government of British Columbia issued a pair of surprising press releases regarding the latest round of Columbia River Treaty negotiations. The brief statements were surprising because few people even knew the tenth round of treaty negotiations, held June 29-30 via web conference, had even taken place.

As with previous press releases, the two sides presented nearly identical information and offered few specifics.

“During this round, Canada responded to a framework proposal previously tabled by the United States and presented a Canadian-developed proposal,” according to the State Department.

“During the most recent round of discussions, Canada responded to a framework proposed by the United States during the previous round of negotiations in Washington, D.C., and tabled a Canadian proposal outlining a framework for a modernized Columbia River Treaty,” read the B.C. press release.

What were the details of the American proposal and Canada’s response? How was the Canadian counter-proposal different?

Neither country was forthcoming with details. Neither offered the media a personal contact with which to follow up.

“Due to the confidential nature of the cross-border negotiations, details of Canada’s initial proposal and of the U.S. framework cannot be made public,” read the B.C. government’s press release, which also noted the next round of negotiation meetings has not been scheduled.

MORE ON CI: A new Columbia River Treaty

The lack of information is frustrating to many because the ongoing negotiations are vital to the long-term health and prosperity of the entire Columbia River Basin.

Although the treaty has no formal expiration date, either side can terminate most of its provisions with 10-years notice. In 2024, the treaty’s flood risk management provisions will automatically change unless both sides forge a new agreement first.

It’s clear the treaty needs updating. Some believe broader reforms are needed.

That makes the present stakes high. And not just for the respective governments at the forefront of negotiations.

An increasing cast of stakeholders is grappling with issues the original framers of the deal did not foresee.

One river, endless suitors

Though it took over a decade to negotiate before it was ultimately signed in 1961 and ratified in 1964, the Columbia River Treaty is a relatively simple agreement.

At its core, the treaty is about the U.S. federal government and the Province of British Columbia (which owns most Canadian obligations and benefits in the treaty) working together to use three Canadian dams to control river flows at the border for two specific purposes: hydropower production and flood risk management.

The Columbia River Basin is a watershed the size of France with over 5 million residents. The entire Pacific Northwest depends on it for economic and environmental vitality.

The modernization of the treaty is a rare opportunity to reshape the distribution of burdens and benefits between the region’s numerous and often conflicting interests.

Limited view: The Columbia River Treaty primarily governs operations at three British Columbia dams and authorized Montana’s Libby Dam (all indicated). Critics want its scope broadened. Map courtesy of NRECA

As the region’s most important economic and ecological artery, the 1,243-mile-long Columbia River has many suitors. Down-streamers want to keep strict flood protections in place. Up-streamers want more flexibility to operate storage reservoirs for local priorities. Indigenous nations and environmental advocates want better flows and new passage at dams for salmon and other aquatic species. Electric utilities want higher revenue. Irrigators want more water. Shipping companies want to protect navigation routes. Recreationalists want reservoir levels to accommodate their activities.

Everyone will need to reckon with climate change, which is expected to shift the American side of the Columbia River Basin from a snow-dominated system toward a more rain-dominated system.

Overall annual flow should stay similar, but timing is likely to change with increased winter flows, earlier peak spring runoff and longer periods of low, hot summer flows.

These trends are already beginning and projected to intensify over coming decades.

The Canadian side of the basin will be impacted in similar ways but is more likely to remain snow-dominated.

Narrow treaty, widespread concerns

With so many groups competing to manage river resources, Columbia River Treaty negotiators are under a lot of pressure. As part of the formal review that started back in 2010, U.S. federal agencies, tribes, states and stakeholders came together to develop the U.S. Regional Recommendation for American negotiators to follow.

This document lays out nine general principles and numerous specific recommendations covering hydropower, flood risk management, ecosystem health, water supply for irrigation and other purposes, navigation, recreation, climate change and the treaty’s governance structure.

The U.S. negotiating team includes five federal agencies led by the State Department.

On the Canadian side, the British Columbia government’s B.C. Decision lists 14 principles that outline its priorities for the modernized treaty.

Additionally, the Canadian negotiating team includes the federal government and three Indigenous nations, all with their own priorities. Local governments in the Canadian portion of the basin have also organized into a formal committee with its own set of recommendations.

MORE ON CI: Americans should moderate expectations on modernized Columbia River Treaty

With so many players and interests in the mix, some observers doubt even an overhauled Columbia River Treaty will be able to handle all concerns.

The original treaty was negotiated and implemented in an era when the legal rights of Indigenous nations were barely recognized and standards for public consultation were much lower.

As a result, the treaty was designed to serve only the narrow interests of federal agencies responsible for hydropower production and flood protection to the exclusion of everything else—including the health of the river’s salmon and other aquatic species.

The decision-making structure used to implement the treaty is also narrow, with little space for public input or oversight.

To address all interest groups’ hopes and fears in the context of future climate uncertainty, Columbia River Treaty negotiators would need to forge numerous complex compromises, radically expand the treaty’s scope to make space for them all and build in flexibility to adjust to changing conditions.

As negotiations enter their third year and stakeholders grow anxious, academics are warning it’s unlikely the treaty alone will produce a comprehensive solution.

What’s an IRBO?

At the September 2019 Columbia Basin Transboundary Conference, an informal group of water resource experts released a draft proposal for broadly reforming water governance in the Columbia River Basin.

The proposal’s authors believe the watershed’s issues “go beyond the current, or likely future, scope of even a ‘modernized’ treaty.”

As a solution, they proposed creating a new joint entity called an International River Basin Organization, or IRBO.

These kinds of organizations already operate in more than 110 international watersheds.

“IRBOs are one way that basins around the world have found they can coordinate better and manage unexpected problems,” says Barbara Cosens, a law professor at the University of Idaho who helped develop the 2019 proposal. “It has provided [them with] greater adaptive capacity.”

Pro IRBO: Barbara Cosens. Photo courtesy of University of Idaho, College of Law

Cosens believes such an organization would improve decision-making in the Columbia River Basin.

“[An] IRBO will unquestionably help meet the deficiencies of the treaty [by providing] a mechanism for enhanced public engagement and transparency, coordination and scientific review, and can operate as a referral resource to address emerging issues,” the governance-reform proposal states. “Those who live in the Columbia River Basin must adapt to climate change, changing energy markets, shifts in land use and a changing society. All will therefore benefit from the formation of a forum that responds to social and ecological change.”

For an example of how such an organization could work in the Columbia River Basin, Cosens points to the Great Lakes Basin. There, eight U.S. states and two Canadian provinces work together through the Great Lakes Commission.

Closed negotiations

Frustrating to many, Columbia River Treaty negotiations are conducted behind closed doors. Within the limits of confidentiality, however, governments have a duty to keep their constituents informed.

This week’s similar press releases notwithstanding, the two sides have taken significantly different approaches to keeping the public updated.

Canada has invested in an extensive public process with a formal advisory council, detailed newsletters and dozens of open-ended public meetings.

In contrast, the United States has limited its engagement with the public to spare press releases and five limited “town hall” meetings, which have allowed for minimal two-way dialogue with attendees.

Canada has granted official observer status to three Indigenous nations based in its side of the basin, which are participating actively as part of the Canadian negotiating team.

So far, the United States has declined to include tribes on its negotiating team, though it has engaged them in periodic consultations and invited representatives to make presentations as expert advisors during formal negotiating sessions.

Turbulent waters: Completed in 1968, Hugh Keenleyside Dam is one of the most controversial dams in B.C. Prior to its flooding, the 140-mile long valley upstream of the dam was home to farms and towns as far north as Revelstoke. Photo by Pat Case

For some basin residents, especially in the United States where public engagement has been less robust, the inability to know what’s really happening is concerning.

Under the State Department’s current public engagement practices, stakeholders have no direct way to voice concerns aside from waiting to submit comments at occasional town hall events or sending messages into a “black box” email account.

Furthermore, there’s no indication of how negotiators handle feedback they receive.

“One thing we learned very early on … was that many of the stakeholders in the basin felt that decisions on operations of the Columbia were made behind closed doors without any public input whatsoever,” says Cosens.

Establishment of an IRBO could alleviate criticisms surrounding lack of transparency in negotiations.

“Track record of failure”

Environmental advocates hope a modernized treaty will support more international collaboration to improve ecosystem health across the whole watershed.

But they worry negotiators will maintain the status quo, with the environment taking second place and each country dealing with it domestically.

They’re also concerned about the treaty’s ability to adapt to changing conditions with climate change.

Several months after negotiations began, a collection of 30 environmental organizations wrote a letter to the State Department expressing concern “that the U.S. negotiating team has distanced itself from the regional expectation that ecosystem function will be a formal purpose of the treaty.”

The letter also emphasizes that the four federal agencies chosen to support the State Department on the negotiating team “have a twenty-five year track record of failure when it comes to managing the hydrosystem in a manner compatible with salmon. … This history underlies our lack of confidence that the current composition of the negotiating team will aggressively advocate for ecosystem flows and other measures necessary to protect and recover [Endangered Species Act listed] populations and resident species.”

Flood control: Built to provide water storage, B.C.’s Duncan Dam has no power-generation facilities. Usually filled by August, its reservoir is continually flooded and drained per Columbia River Treaty operations. Photo by Graeme Lee Rowlands

Though negotiating sessions would likely still be confidential, an IRBO could help facilitate better public engagement to help people understand what is happening and feel their voices are being heard and responded to.

Cosens says that in the Great Lakes Basin an umbrella organization exists as a representative of the two countries.

That group serves as a point for coming together on new issues as they arise and educating the public on current matters. A citizen’s advisory body and a science advisory body offer advice on new and existing problems.

As part of this mission, the Great Lakes Commission holds an open forum every two to three years to update the public on important developments.

“There’s an ongoing learning process that takes place,” says Cosens.

“Community of the Columbia”

Cosens recognizes concerns that an IRBO could be just an “academic idea” or another top-down bureaucracy. She emphasizes the proposal she helped write grew out of recently strengthened institutional connections across the international border.

“If done right, I think [an IRBO] will build a regional approach to problem solving and resilience in the watershed,” says John Osborn, a Washington-based conservationist. “But to get there you have to start with understanding. You have to build trusting relationships. You have to build a ‘community of the Columbia.’

For more than six years, Osborn has been working with Indigenous nations to coordinate an annual conference series called One River–Ethics Matter. The effort aims to bring people together to reflect on the history of the watershed and forge connections that can help guide its future.

MORE ON CI: New pressures threaten White Salmon River corridor

For Osborn, gatherings like this are a catalyst for people to identify shared goals. Ultimately, he says overcoming division is about “introducing people to each other and allowing [them] to work together for a common purpose.”

In such a large and diverse region, where people have sometimes neglected to even include both countries on maps of the watershed, simply broadening the decision-making dialogue would be a positive step. What is a treaty, after all, if not a relationship?