Environmental groups say the plan fails to address serious concerns. The federal government isn’t saying much of anything

Big land, big plan: The Environmental Restoration Disposal Facility is a landfill for low-level waste within Hanford Site, a 580-square-mile section of semi-arid desert in southeast Washington. A massive solar-energy facility is being planned for another part of the site. Photo: DOE

By Andrew Engelson. August 14, 2025. In June, the environmental organization Columbia Riverkeeper filed a lawsuit against the U.S. Department Energy (DOE) seeking to compel the agency to release documents related to a proposed plan that would lease 8,000 acres of the Hanford Nuclear Site to produce renewable energy.

At first glance, the plan—in which Hanford would contract with a private firm to build a one-gigawatt solar energy farm on land in the southern end of the 586-square-mile reserve—sounds promising.

The Hanford clean energy proposal, which was awarded to the Chicago-based private firm Hecate Energy LLC, is by far the largest of the Biden administration’s Cleanup to Clean Energy initiative sites, which also include proposed projects at DOE sites in Idaho, Nevada and South Carolina.

“We are going to transform the lands we have used over decades for nuclear security and environmental remediation by working closely with tribes and local communities together with partners in the private sector to build some of the largest clean energy projects in the world,” said U.S. Secretary of Energy Jennifer M. Granholm in 2023. “Through the Cleanup to Clean Energy initiative, DOE will leverage areas that were previously used to protect our national security (to generate) clean energy that will help save the planet and protect our energy independence.”

However, environmental groups have since become frustrated with what they say is a lack of transparency from DOE regarding the project, especially unanswered questions about how the plan would affect the multi-billion-dollar cleanup of radioactive contamination at Hanford.

Simone Anter, senior attorney at Columbia Riverkeeper, speaks for one of these groups.

“We’re generally very supportive of the need to increase green energy production,” Anter told Columbia Insight. “But it’s essential that this transition is socially just and environmentally sound, particularly in this area, which has been rife with cleanup challenges.”

Anter said that in 2023, soon after DOE sent out a request for qualifications for the contract, Columbia Riverkeeper submitted comments and reached out to DOE for more information about the project.

“Their responses to us did nothing to quell our concerns and did little to answer our questions,” said Anter.

Keeping on keeping on: Cleanup at the Hanford Site is scheduled to go on until 2086. Here, work continues on an interim surface barrier at U Tank Farm. Photo: DOE

In early 2024, Columbia Riverkeeper wrote a letter to DOE asking for more information about the project, which was signed by other organizations, including the Oregon Chapter of the Sierra Club and Washington Physicians for Social Responsibility.

Among their concerns were whether small modular nuclear reactors (SMNR) would be considered as a source of “clean energy” on the site, and what, if any, consultation DOE was doing with Tribes that have a stake in the site, including the Yakama, Nez Perce and Umatilla.

While DOE and the Pacific National Laboratory tout SMNR as a new frontier in clean energy, others point out that SMNRs still produce high-level nuclear waste.

“We didn’t get a response,” Anter said of her organization’s request for more details from DOE.

The organization filed a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request for documents related to the project.

DOE failed to respond to that request, so, in June, Columbia Riverkeeper filed an FOIA lawsuit.

“We have real concerns that [DOE], with this proposal, is going to lose sight of cleanup,” said Anter. “We’re already seeing the Department of Energy struggle to meet cleanup deadlines.”

The Department of Energy and media contacts for the Hanford site did not respond to multiple requests for comment from Columbia Insight.

Communication breakdown

Anter isn’t optimistic that government transparency will improve.

She said that during previous administration, DOE’s FOIA officer had been in communication with her group. Since Donald Trump assumed office in January, however, she said all attempts at communication have been met with silence

“This administration is very clearly anti-clean energy and pro-nuclear energy. And so if anything, our concerns for this area are even greater,” said Anter.

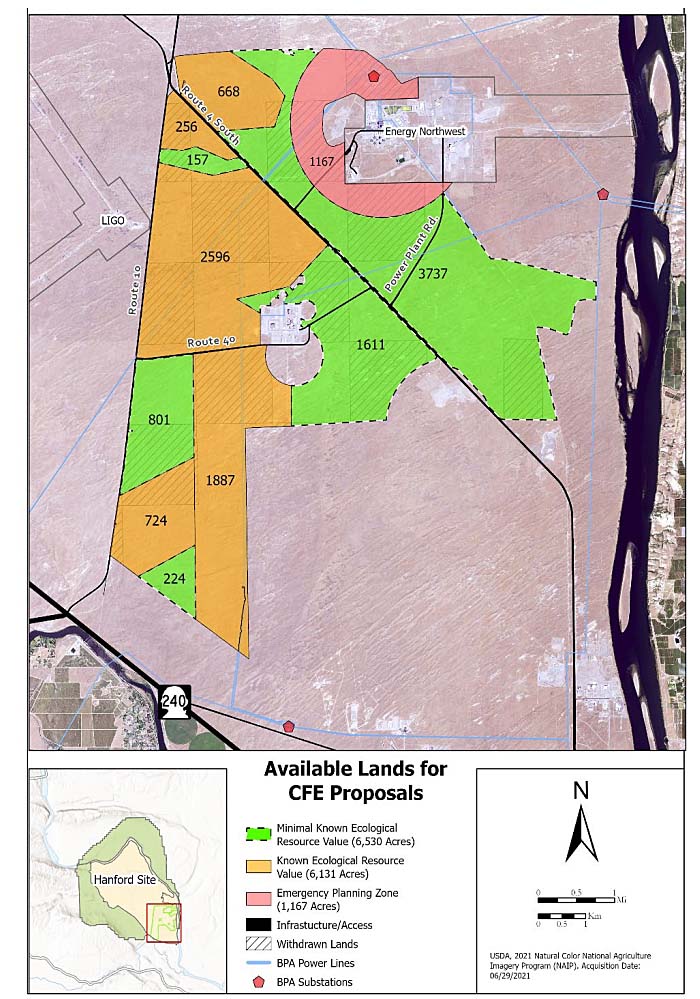

Lands designated for CFE (Carbon-Free Electricity) projects are located in the southeast corner of the Hanford Site. Map: DOE

Hecate Energy was announced as a partner in 2024 to develop a one-gigawatt solar photovoltaic system with battery storage on 8,000 acres on the Hanford site.

Jared Wren, a spokesperson for Hecate, told Columbia Insight that the company has received no indication from the new administration that anything in the plan has changed.

“Our team at Hanford informs me that they do not have a substantive update regarding the project at this time,” said Wren.

Funding for Hanford cleanup stayed at the same level as last year in the recently passed federal budget, according to Anter. But in early 2025, because of cuts to DOE by Elon Musk’s Department of Government Efficiency (DOGE) and related executive orders, Hanford lost 50 staff members from a workforce of 300.

In addition, in April, Hanford’s manager, Brian Vance, announced his resignation. In June, he was replaced with acting manager Brian Harkins, who has more than 30 years of experience in various roles at Hanford.

Nikolas Peterson, executive director of Hanford Challenge, an organization that advocates for worker safety at the Hanford site, also has questions about the solar energy plan and how it interacts with current cleanup efforts.

“I don’t want it to distract from the actual cleanup,” said Peterson. “As they’re transporting more and more waste from the site, that’s a concern. And if there are more people working on the site and if there’s an accident or something like that, that could be a potential worker safety issue.”

Radioactive soil

The 14,000 acres Hanford made available for clean energy is at the southern end of the site, just outside Richland, Wash.

The proposed clean energy site is adjacent to the Columbia Generating Station (CGS), the only active nuclear plant generating electricity in the Pacific Northwest.

The nuclear plant, which opened in 1984, effectively delayed final cleanup of the 618-11 burial site next to CGS, which contains low-level and high-level waste. The cleanup of that site isn’t expected to be complete until 2030.

“The presence of CGS’s parking lot on top of that burial ground, and workers going in and out of CGS, hasn’t allowed regulators a chance to get in there and classify the waste that’s in there, what’s causing contamination and to figure out a plan to clean it up,” said Anter.

Staying power: In 1972, a band of five elk were spotted on the Hanford Site. The herd has grown at times to more than 2,000 animals. Photo: DOE

In addition, the proposed 14,000-acre clean energy site is adjacent to the 324 Building, in which research on radioactive materials was conducted between 1966 and 1996.

The building was slated for demolition, but in 2010 regulators discovered a large area of highly radioactive soil below the building and postponed tearing it down.

“There is a real concern from us about developing this and having more workers on site and more people exposed,” to places like the 324 building, said Anter.

She also said that DOE, despite promises to engage with Tribes about the project, provided minimal consultation and hasn’t explained why a tribal clean energy proposal that was submitted wasn’t selected for the site.

The Confederated Tribes and Bands of the Yakama Nation did not respond to a request for comment.

“We have a lot of unanswered questions and concerns,” Anter said of the project, and Columbia Riverkeeper’s lawsuit aiming to compel DOE to be more forthcoming with information. “We simply want engagement and answers.”