The Port successfully petitioned the state for an executive order to suspend environmental regulations in order to save jobs

It’s really beneath them: Established in 1958, Port of Morrow is one of Oregon’s most largest industrial centers and chronic polluters. Photo: Port of Morrow

By Kendra Chamberlain. February 27, 2025. A group of 26 conservation nonprofits, grassroots organizations and community leaders have signed a letter sent to Ore. Gov. Tina Kotek alleging the Port of Morrow, located along the Columbia River in northeastern Oregon, intentionally misled the governor about its wastewater storage capacity while seeking an emergency order earlier this year.

The Feb. 21 letter, authored by advocacy group Oregon Rural Action and undersigned by a former Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ) administrator and a former Morrow County commissioner, among others, requests that the governor rescind an executive order she made in January that allows the Port of Morrow to violate its wastewater permit.

“We believe this decision was misguided and may have been based on incomplete, misleading, or inaccurate information,” the letter reads. “[The executive order] needlessly allows for increased pollution during the high-risk winter season when the risk to the public is highest, threatening to worsen an already severe crisis.”

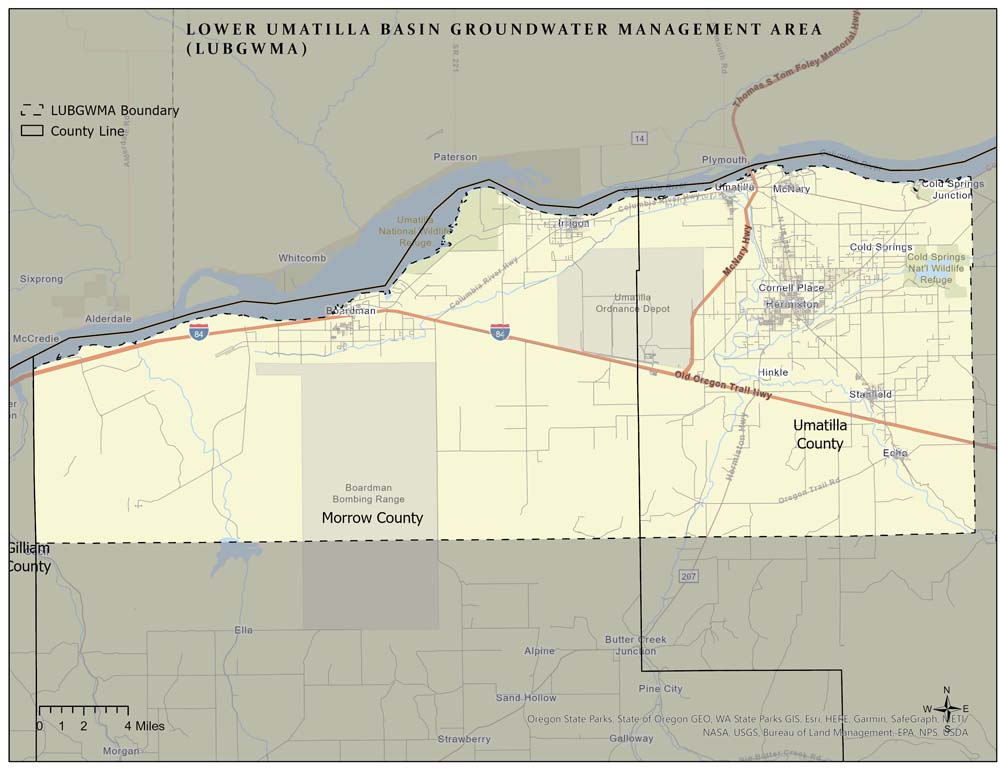

The letter also requests the governor declare a public health and environmental emergency in the Lower Umatilla Basin due to nitrate pollution in groundwater within the Lower Umatilla Basin Groundwater Management Area.

A spokesperson for the Office of Governor Kotek told Columbia Insight in an email that her office had received the letter and is reviewing it.

The Lower Umatilla Basin Groundwater Management Area, which spans 550 square miles across Morrow and Umatilla counties along the Columbia River, has been plagued with high levels of nitrates in groundwater since the 1990s.

A report released by Oregon DEQ in January found that nitrate contamination, driven primarily by agricultural practices, has continued to worsen over the past decade.

“The people who are affected by this pollution, the victims of pollution, are low-income, non-English speaking, disproportionately Latino and immigrants, working class,” Kaleb Lay, director of policy and research at Oregon Rural Action, told Columbia Insight. “They don’t have a lot of power on their own, but that’s why we’re supposed to have regulations and laws—so the polluters can’t get away with this sort of thing.”

UPDATE, Feb. 27. 2025: Since the publication of this story, Gov. Kotek responded by letter to the Feb. 21 letter from Oregon Rural Action. Gov. Kotek’s largely pro forma response did not address concerns about the Port of Morrow’s “incomplete, misleading, or inaccurate information.” Gov. Kotek’s letter, in part, reads:

“In the last several years, the Port of Morrow has worked more closely and intentionally with the Oregon Department of Environmental Quality (DEQ), sticking to a permit compliance schedule that is a critical part of the long-term strategy to reduce nitrate contamination in the region. Industries at the Port of Morrow took voluntary measures to reduce wastewater in the basin headed into this non-growing season, and this will be the last winter when land application will occur due to the upgrades that the Port of Morrow is currently making and the updated schedule that DEQ has required.”

The letter goes on to say:

“Remediating the groundwater contamination in the basin will take decades. … I want residents who have been impacted by this water contamination to know that the state and our partners have been working with urgency to deliver solutions. Free testing and retesting, treatment options, and water delivery will continue to be provided by the State of Oregon to all residents in the LUBGWMA whose water tests higher than 10mg/L of nitrate—at no cost to residents.”

Chronic polluter

The Port of Morrow, Oregon’s largest industrial port east of Portland, accepts wastewater from industrial businesses such as food processing plants, data centers and a PG&E-owned power plant.

The Port then moves that nitrogen-rich wastewater upgradient for land application on agricultural fields.

Specific conditions must be met for the land application of wastewater. The Port is only allowed to dump a certain amount of wastewater at a time to agricultural land in order to ensure the nitrates don’t reach groundwater stores.

Map: State of Oregon

Land application during the rainy season is especially tricky, because if the soil is already saturated with water (from, say, a run of rainy weather), the Port must wait until the soil dries before spreading wastewater.

The wastewater is stored in lagoons until it can be disposed of.

“The fundamental problem is the Port has chronically—for years, years and years—produced way more [wastewater] than the fields where they’re allowed to dispose of it can possibly handle, which creates this leaching problem, which leads to permit violations and contaminates the groundwater,” said Lay.

A 2022 investigation by the Oregon Capital Chronicle found the Port had violated its wastewater permits for the previous 15 years. In the last two years, DEQ has fined the Port more than $3.1 million for permit violations.

The Port is in the midst of building out more lagoons to store the wastewater, a move that it hopes will end future winter water dumps on the land. Those lagoons are expected to be completed by November 2025.

Executive order suspends rules

Amid a spell of unusually wet weather in December 2024, the Port of Morrow requested the governor sign an emergency order that would allow it to violate wastewater regulations, arguing that the predicted precipitation and freezing conditions would overwhelm its wastewater storage capacity, thus forcing the Port to exceed its land-application capacity.

Without the order, the Port argued, it wouldn’t have any choice but to stop accepting wastewater, because it wouldn’t have any place to legally put it. That decision might have forced the industrial facilities generating wastewater to cease operations, which in turn could have led to “furloughs of potentially thousands of workers resulting in substantial economic harm to the region and the State of Oregon,” according to Gov. Kotek’s subsequent executive order (EO), issued Jan. 13.

“Allowing them to violate without holding them accountable is just giving them a free pass to pollute.” —Kaleb Lay

The EO granted the Port of Morrow’s request and declared a state of emergency “due to risk of economic shutdown” in Morrow and Umatilla counties.

The EO allows the Port to apply wastewater only to fields that are down-gradient from domestic wells or those that are designated as low-risk for contamination.

“I did not make this decision lightly,” Kotek said in a news release. “We must balance protecting thousands of jobs in the region, the national food supply, and domestic well users during this short period of time during an unusually wet winter.”

Kotek’s order allows an exception to the Port of Morrow’s wastewater permit only from Jan. 15 through Feb. 28.

The Port of Morrow officially invoked the EO’s use on Feb. 17, nearly a month after the EO was issued.

Port of Morrow Executive Director Lisa Mittelsdorf told Columbia Insight in an emailed statement that the Port was able to delay invoking the order thanks to conservation efforts and management of its storage-lagoon capacity.

“The order was invoked in accordance with its terms only when the Port determined that available storage capacity would be exhausted within seven days. As required by the order, the Port restricted land application to two farms with no down-gradient domestic users of alluvial groundwater,” the statement reads.

Worrying precedent

Oregon Rural Action, however, doesn’t think the Port of Morrow was being honest in its emergency order request.

In its letter to Gov. Kotek, the group compared statements and arguments used in the emergency request against the Port of Morrow’s own monthly reports to DEQ.

“It’s a paper-thin argument that falls apart right away,” said Lay.

Kaleb Lay. Photo: Keith Schneider/Circle of Blue

He said the Port’s DEQ report states its storage capacity was only at 44% at the end of December, with roughly 335 million gallons of capacity available, despite the Port’s claim to the governor’s office that it was running out of storage space.

“At the same time, they were expecting to produce less wastewater than they had in the previous two months,” said Lay. “So for the remainder of the winter [including January and February] they had more than half their wastewater storage available to them, and were expecting to make less [wastewater in January and February], which would lead one to believe that they could store all of what was left without much trouble at all.

“It just doesn’t seem like that due diligence was done in the making of this decision to grant them this power.”

The EO is set to expire at the end of this week, but “every day counts,” according to Lay.

And concerns persist over the setting of a controversial precedent based on faulty information.

“The permit conditions exist for a reason. They’re not perfect, but every violation that [occurs] is a violation because [the permit] is trying to prevent contamination of groundwater. Allowing them to violate without holding them accountable is just giving them a free pass to pollute,” said Lay.

There is actually no “Port of Morrow.” It is a front for the businesses that operate in that area. Years ago Sam Boardman had a dream to develop that area, and that dream has been fulfilled.

Unfortunately, all of those dreamers have been bought out by the folks who give capitalism a bad name. And, by and large, any decent folks who used to object to the utterly bizarre and self destructive business practices of folks out of Idaho have been run off, out, or otherwise silenced.

There is a much better way to handle wastewater, they choose not to use it. By making those wrong choices, they are simply trashing themselves, their employees, and our collective future.

Shame on the Governor of Oregon for “going along with this” and letting them “get away” with it.

Thirty-three years ago Lamb-Weston burned a plant they didn’t own, got 31 million dollars and title to the plant, and went on their merry way trashing an area turning a valuable vegetable into sickening French fries.

They “got away” with it then, they will “get away” with it now. Unless the climate change and global warfare they create ends their ability to grow and market their product.

Think Lamb-Weston Connell, WA. Think Frank “Gib’ Lamb and W.L. “Shine” Minnick. Think H.H. Hahner, affectionately known as “Dutch”, Glenn Bean and Whitman College. Think two-faced folks selling top grade product to the U S military, and garbage to almost everyone else.

Been there and done that.

Thanks for your reply. It seems that this is another instance when fact checking was not done before making a decision.