The Selkirk region’s endangered grizzly bear population bares its first confirmed female sighting by wildlife biologists in four decades

Cubs fan: Confirmation of this mother grizzly (left) raised cheers among wildlife biologists. And people who just like bears. Photo by USFWS

The original version of this story mistakenly characterized the Selkirk Mountains as part of the Cascade Range. This version of the story has been corrected. —Editor

By Jordan Rane, August 5, 2021. Endangered wildlife recovery is a slow, uncertain process—especially at the top of the food chain.

That’s what makes the July confirmation of a female grizzly in Washington’s Selkirk Mountains grizzly bear recovery area so monumental. Until June, wildlife biologists hadn’t seen a female grizzly in the area since 1981. That’s 40 years.

State biologists became aware of a mother bear with her three cubs through images captured on wildlife cameras in a remote patch of the Selkirks.

In an announcement released on July 15, the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife said U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists had captured the elusive sow on U.S. Forest Service land about 10 miles from the Washington-Idaho border. After USFWS biologists performed a general health check, the grizzly mom was fitted with a radio collar for tracking before being released near Metaline Falls in northeastern Washington and reuniting with her cubs.

Biologists believe this is a local Washington bear, not one from outside the state—a finding that counts as a major success in efforts at grizzly recovery plans.

“It proves that we have grizzly bears in Washington and that they can coexist peacefully with people,” Joe Scott of Conservation Northwest’s grizzly program told The Spokesman-Review. “Without grizzlies in the Cascades the job is not done and the ecosystem is a mere shadow of what it once was—and can be again.”

Conservation Northwest has identified the Cascades to Rockies corridor as among the most critical in the Pacific Northwest for wildlife also including Canada lynx, wolverines, mule deer, wolves and other species.

USFWS biologists currently consider grizzlies to be a separate subspecies of brown bears.

Coming back … slowly

Grizzly bears were listed as endangered in Washington’s Cascades in the mid-1970s. When recovery efforts began around the same time, the grizzly population in the Lower 48 was estimated at about 700 animals—a more than 98% drop from an estimated population of over 50,000 a couple centuries ago.

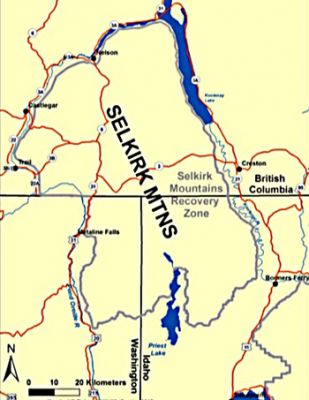

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has been leading a grizzly monitoring program in the Selkirk Mountains Ecosystem since 2012. Map USFWS

While grizzlies have lumbered back to about 6% of their former range according to wildlife biologists—about 1,900 are now estimated in the Lower 48, compared with 30,000 in Alaska—numbers in the Selkirk grizzly bear recovery area are much slimmer.

Selkirk is one of six such zones in the United States identified by the federal recovery plan for grizzlies.

Just less than 80 grizzlies now roam this vast mountainous terrain straddling the border between northeastern Washington, Idaho and British Columbia according to U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service biologists.

An estimated half of that population resides south of the border in Washington. That’s 40 bears. An even rarer sight than just any grizzly bear in this region is a female grizzly.

“Grizzly bears once occupied much of the Cascade and Selkirk ranges, but it’s taken 40 years since recovery started to confirm the first known female in Washington,” Rich Beausoleil, a bear and cougar biologist with the Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife told the Associated Press after this summer’s discovery. “That’s pretty remarkable.”

Tribal interest

The discovery is also of great importance to northeastern Washington’s Kalispel Tribe, which launched its own natural resources department about 30 years ago, working to recover grizzlies and other native species to their traditional lands.

“Hopefully we can continue to survey and collar bears in this portion of the recovery area to build an accurate population model and better understand how they are using the Selkirk Mountains and the adjoining ecosystems,” Bart George, a biologist with the Kalispel Tribe, recently told to The Spokesman-Review’s Eli Francovich. “The Tribe will continue to support grizzly bear research and recovery efforts while the population moves toward federal delisting criteria.”

Nationally, grizzly bears are currently listed as a threatened species under the federal Endangered Species Act.

In Washington they remain classified as endangered.