In 2020 the Department of the Interior kiboshed a long-running grizzly restoration study. Its authors and supporters still want answers

Can’t go home again: The Cascades would support a grizzly return. The locals not so much. Photo: Princess Lodges

By Jordan Rane. January 13, 2022. In 2015, a trio of government groups launched the most ambitious bear recovery study ever undertaken in the Cascade Range. In 2020, just as the Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan for the North Cascades Ecosystem appeared to be nearing its conclusion, it was abruptly cancelled.

Almost no one knows exactly why.

Now the target of a lawsuit brought by the Arizona-based Center for Biological Diversity, the aborted program provides a fascinating example of wildlife management that seems to eschew collaboration and transparency, produces unknown public expenditures, alienates researchers and turns creatures as mighty as grizzly bears into political footballs.

We asked contributing editor Jordan Rane to investigate. —Editor

In 2015, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, National Park Service and Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee—a cross-agency organization spearheading conservation of the threatened species in six designated wilderness areas across the Northwest—launched a program aimed at studying the possible restoration of grizzlies in one of their most decimated yet still viable habitats in North America: Washington’s North Cascades.

The Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan for the North Cascades Ecosystem—which began with a multi-year environmental impact study—was more or less unprecedented. Its intent was to study the feasibility of transplanting the iconic bear into a vast wildland situated between farms, ranches, rural communities and large coastal cities.

Hitting a snag: At the Selkirk Mountains corral site barbed wire is used to obtain hair samples from bears for genetic testing. Photo: USFWS

In 2020, however, the expansive study was suddenly and unexpectedly terminated by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

Aside from citing local opposition to the federal program, then Interior Secretary David Bernhardt provided no concrete explanation for the decision to end the program.

The unexpected cancellation of the project took government biologists, wildlife managers and others aback.

“It was somewhat of an abrupt termination,” says U.S. Fish and Wildlife biologist Wayne Kasworm, a senior Interagency Grizzly Bear Committee member and principle figure for grizzly recovery programs in Washington’s Selkirk Mountains and Montana’s Cabinet Mountains. “It was a bit of a surprise to those of us who’d been working on it for years.”

MORE: Washington’s contentious spring bear hunt put on hold

Surprise or not, what remains unclear is why a large and publicly funded study about a possible path to grizzly bear recovery in national parkland and other public wilderness areas was muted before it was able to issue its conclusions.

Shortly after the decision was announced, the Center for Biological Diversity filed a lawsuit with the U.S. District Court for the District of Columbia challenging the decision to scuttle the program and seeking to have it resumed.

The outcome of that lawsuit is yet to be decided.

No matter what the verdict, understanding its impact and implications requires a look at a decades-long process that’s left many of its participants dissatisfied and confused.

Grizzlies in the Cascades

First, a bit of regional grizzly history.

Over a century ago, grizzlies roamed the North Cascades in large numbers. Since 1980, however, they’ve been officially designated as “endangered” in Washington.

MORE: Alarming loss: As urban boundaries expand, wildlife habitat is being destroyed

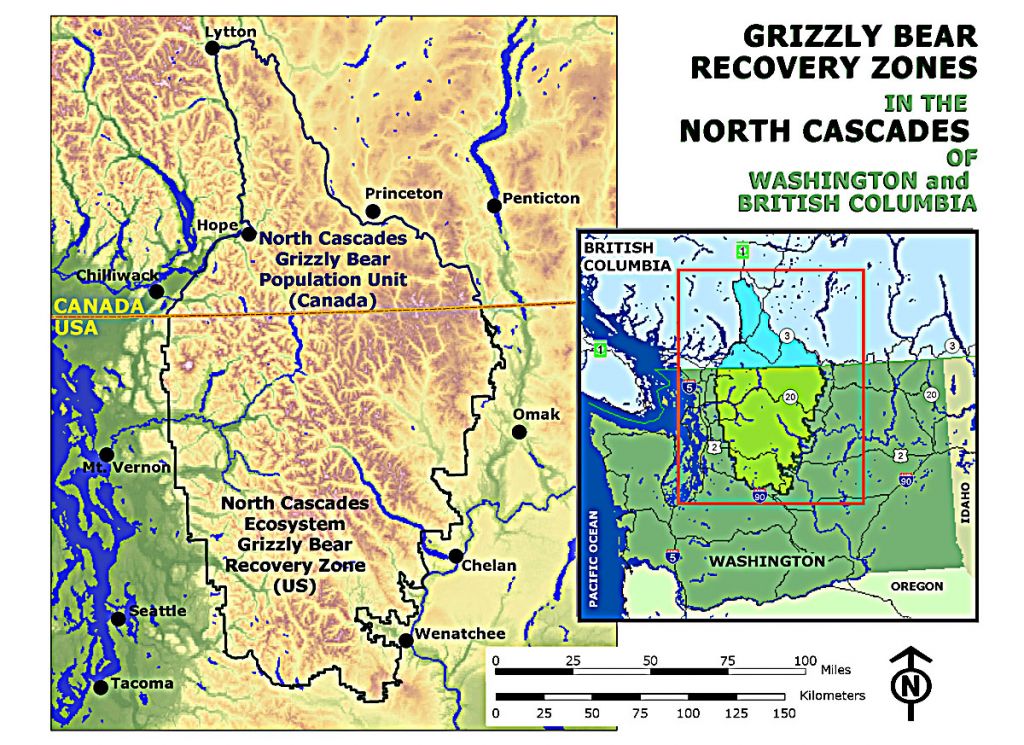

How many grizzlies currently inhabit the North Cascades Ecosystem, which covers nearly 10,000 square miles of mainly public land in North Central Washington, with an additional 3,800 square miles rolling north into British Columbia?

“To our knowledge, there is no functioning population of grizzly bears in the Cascades,” says the Montana-based Kasworm, who has worked with grizzlies for nearly 40 years. “We’ve done a lot of looking there, and—aside from a few recent sightings north of the border in British Columbia’s Manning Park—the last verified sighting of a grizzly bear in the much larger U.S. portion of the North Cascades Ecosystem was in the late ‘90s. So I’d have to say at this point there’s a very good chance we’re looking at zero grizzly bears in the Cascades.”

Sudden stop to study

Introduced in 2015 during the Obama administration, the Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan for the North Cascades Ecosystem (sometimes referred to as the North Cascades Grizzly Bear Recovery Program) was moving into its public comment period when President Donald Trump’s incoming Interior Secretary Ryan Zinke took office in March 2017.

After initially halting work on the plan’s environmental impact statement in 2017, Zinke ordered it to resume the following year.

Can’t bear it: Former Interior Secretary Bernhardt. Photo: Official White House photo by Stephanie Chasez

In 2020, however, his successor, Interior Secretary David Bernhardt, once again halted the program. This time for good.

“The Trump Administration is committed to being a good neighbor, and the people who live and work in North Central Washington have made their voices clear that they do not want grizzly bears reintroduced into the North Cascades,” Bernhardt stated in a press release.

“My constituents in Central Washington [share] my same concerns about introducing an apex predator into the North Cascades,” echoed U.S. Representative Dan Newhouse (R-Wash.), who Bernhardt called a “tireless advocate” on the issue, in a separate press statement. “Homeowners, farmers, ranchers and small business owners in our rural communities were loud and clear: We do not want grizzly bears in North Central Washington.”

Despite those citations of public opposition, the Center for Biological Diversity’s December 2020 lawsuit filed against the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and National Park Service alleges that Trump administration officials (specifically Bernhardt) illegally stopped grizzly recovery efforts in the North Cascades.

“One of our big quandaries is that there was nothing to explain why the program was discontinued and no supporting documentation to support this termination,” says Sophia Ressler, staff attorney for the Carnivore Conservation Program with the Center for Biological Diversity, which classifies the lawsuit as an Endangered Species Act violation case.

Decades of research abandoned

Although the Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan for the North Cascades Ecosystem was officially launched in 2015, it was preceded by decades of research and fieldwork on the elusive (or nonexistent) grizzlies of North Central Washington.

A 1991 agency evaluation confirmed the North Cascades Ecosystem could support grizzly bears. So did a 2002 habitat assessment. So did a separate peer-reviewed scientific study that, says Kasworm, concluded the ecosystem could handle 280 grizzly bears.

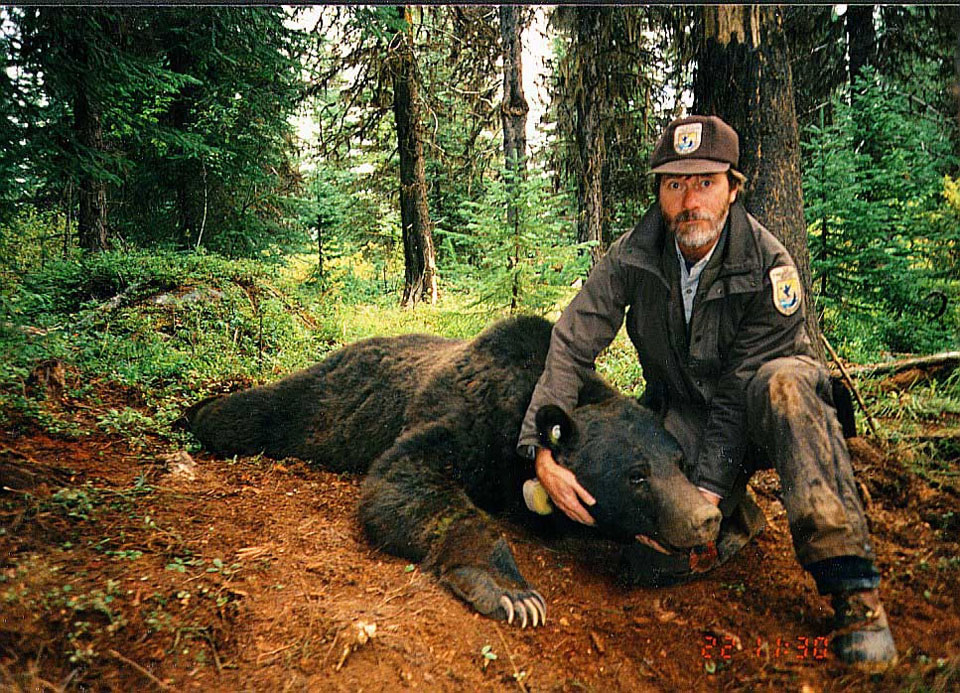

Bear down: Wayne Kasworm with male grizzly captured as a research animal in the Yaak River drainage in Montana. Photo: USFWS Mountain-Prairie

This doesn’t mean the area would’ve come close to carrying that population of grizzlies anytime soon, if ever.

According to a series of frequently asked questions on the National Park Service website about the Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan, it’d take the North Cascades 50 to 125 years to establish a self-sustaining grizzly population—and that taking into account the hypothetical transplant of a small number of bears to get things going.

The Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan was geared toward assessing a range of alternatives to support grizzly bear recovery in the area—including an option to simply stand pat.

“One potential option at the end of our study could’ve been just to do nothing,” says Kasworm. “We could’ve gone through that whole process and decided to simply choose the ‘no action’ option—but we didn’t get that far. We were just told to stop.”

The other end of the spectrum would involve bringing in grizzlies from elsewhere to repopulate the area. That would have represented a far more difficult and contentious move.

“It’s one thing to try to manage and increase an existing grizzly bear population and another thing entirely to try and restart one where there really isn’t much there,” says Kasworm.

Potential grizzly recovery area in the North Cascades. Map: USFWS

Kasworm has been involved in what may be the first and only project of this kind to date—in the Cabinet Mountains of Northwest Montana and part of the Idaho Panhandle, home to the Cabinet-Yaak Grizzly Bear Recovery Area, which was down to six bears in the 1980s.

“We went through a similar type of process there—and ran into a public that was really unsure about the idea of bringing bears in,” says Kasworm. “It was controversial because no one had really transplanted grizzly bears to another place with the intention of augmenting the population.”

Ultimately, the public agreed to a test run. Between 1990 and 1994, four female bears were brought in from British Columbia to the Cabinet Mountains.

“All of them were young with no history of conflicts with people. We radio-collared them, put them in the Cabinets and at least one of those bears stayed and reproduced,” says Kasworm.

The program was allowed to continue. A small but stabilized population of grizzlies in the Cabinet-Yaak has since been deemed a recovery success story.

What did the public want?

By the time Interior Secretary Bernhardt ordered the Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan for the North Cascades Ecosystem ended, the study had consumed years of research, planning and fieldwork.

It had produced an EIS draft (released in 2016) that according to Kasworm was “getting near two inches thick.”

And it had gathered reams of public feedback, which has yet to be fully evaluated.

Divided public opinion on the issue was pretty much a given. Even so, between 2017 and 2019, Tribal consultations, more than 70 stakeholder briefings and at least 10 public meetings related to the North Cascades Bear Recovery Program were held on both sides of the Cascades.

Public comments exceeded 143,000, according to the Department of the Interior.

MORE: Did Creswell bear need to be killed?

Experience in Montana provided Kasworm with some background to relate to the Washington public during open meetings about what might occur in the Cascades if grizzlies were to be reintroduced there. Following presentations, he fielded just about every question in the grizzly book, including the obvious ones.

What are the chances of human injury? How many people have been killed by grizzlies over the past century? What are the potential impacts on livestock or the timber harvest? Why would we even want to recover grizzly bears?

That last question would occasionally come up during testier public forums.

“Well, we have the Endangered Species Act—plus the mission of a national park to maintain its natural environment and the species that reside there,” Kasworm would answer. “And because this is a recovery area for bears, there’s interest on the part of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to look at this program and go through a public process …” And so on.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“Grizzly bears occupy less than 5% of their historic range, and the North Cascades presents prime habitat.” —Andrea Zaccardi, Center for Biological Diversity[/perfectpullquote]

“It was just part of the whole process,” says Kasworm. “There are places where you run into a lot of supporters and it’s an easy meeting. And there are places where you run into more opposition. I’ve been through controversial subjects with grizzly bears a lot in the last 38 years. I recognize that it can be an emotional issue and people can get excited about it on both sides. But I’d say for the most part those public comment meetings went pretty well.”

Precisely how well is hard to say with a recovery plan that remains incomplete. But there was an overall trend.

Don’t miss out: subscribe to Columbia Insight. It’s free!

The nature of that trend, however, depends on who you ask about it.

“I’d say we had more support on the west side of the Cascades, more opposition on the east side, and if you were to take in all the comments in total there was just a good deal more support in general,” says Kasworm, who is reluctant to say much more than that. “I can’t say too much about the comments because they weren’t completed. I have some idea where they were going … Since we didn’t get done with the comments I think it would be premature for me to say [anything] about the comments and where all of that was going.”

“Recent public comment periods and past polling show that roughly 80% of respondents support grizzly bear restoration in the backcountry in and around North Cascades National Park, including residents on both sides of the Cascade Crest,” said Chase Gunnell, communications director for Conservation Northwest, in a 2020 report from Centralia, Washington’s The Chronicle.

In its July 7, 2020, announcement of the project’s termination, the Department of Interior stated “overwhelming opposition was received for the plan.”

Will the study be unbroken?

Did the program’s sudden termination come as a shock to those who’d spent years working on it?

“Yeah,” says Kasworm, wary of going much deeper into a matter now in litigation.

Was there any clear explanation for the decision?

“Not that I’m aware of is the best thing I can say here,” he says. “The reasons for the termination lie with the Secretary of the Interior, Mr. Bernhardt, who made that call a couple of years ago.”

Was it frustrating?

“I probably shouldn’t say it, but yeah it’s frustrating. I mean, you work on something like this for several years. You’re partway through the whole thing. You’ve invested a whole lot of effort and money in the process. Then, all of a sudden, people just say ‘Stop.’ So yeah, there’s a certain degree of frustration.”

Ursus politicus: Grizzlies are making tentative steps in the Selkirk Mountains. Obstacles remain. Photo: USFWS

Kasworm isn’t the only one frustrated by the decision.

“It is truly disappointing that the Trump administration has abruptly decided to pull the plug on a years-long effort to recover grizzly bears in the North Cascades,” Andrea Zaccardi, a senior attorney with the Center for Biological Diversity, told The Chronicle in 2020. “Grizzly bears only occupy less than 5% of their historic range, and the North Cascades presents prime habitat for grizzly bears. Their recovery there is critical to the overall recovery of grizzly bears in the U.S.”

Currently, the Center for Biological Diversity’s lawsuit has been assigned to a judge, and further discussions with agencies under the Biden administration are pending.

The lawsuit’s ultimate aim is to get the Grizzly Bear Restoration Plan for the North Cascades Ecosystem reinstated.

“We’re waiting for Biden’s appointments and our hope is that we’ll have a conversation with the agencies and move the program forward,” says Ressler of the Center for Biological Diversity. “The people now in charge of the agencies in Washington are very supportive of it. The area we want to reintroduce is a very important place to do so—with a lot of grizzly habitat and not a lot of people.”

As a veteran biologist and principal member of the program, Kasworm flatly refers to the turn of events in the North Cascades Ecosystem as “not exactly a high point.”

He then turns to a broader picture of notable triumphs in grizzly conservation—including the ongoing recovery of a population in Montana’s Cabinet Mountains and collaring a female grizzly in Washington’s Selkirks this past year.

“That’s the first female grizzly bear ever captured in the state of Washington,” says Kasworm. “So there’s been some progress happening too.”

Columbia Insight requested interviews or comments for this story from former Secretary of the Interior David Bernhardt and U.S. Representative Dan Newhouse. At the time of publication, no replies had been received. This story will be updated should either provide a response.

i KNOW OF SOME FOLKS HAVE SEEN GRIZZLY UP BY TROUT LAKE WASH. I FOR ONE DO NOT WANT THEM AROUND !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Grizzlies are a super important part of the ecosystem here in Washington. Their reintroduction to their historic range is way overdue, and we need to do everything we can the help bring these bears back to where they belong. Some slight modifications to human behavior can help alleviate any potential conflicts that may arise (locking trash cans, hazing problem bears, carrying bear spray and making noise while in the backcountry, etc..). I really hope this happens soon

I understand the importance they play in the ecosystem, and the threat they are to my family living in this neck of the woods. All in all, I’d rather restore the ecosystem and enjoy its fullness and take the risk. Living amongst them is possible with the proper preparedness. And it could be rewarding.

Sam, Dawn Stover reported in a Sept. 2020 article on cougars for Columbia Insight: “There is no place in Washington that is more than 13.6 miles from any human development.”