Critics are concerned that extractive interests are “jumping to the front of the line.” But the federal agency has many stakeholders to please

Upper management: In northeastern Oregon, plans for balancing logging, grazing, recreation and conservation interests in the Blue Mountains are being reviewed. Photo: Jurgenhessphotography

By Rick Haverinen, Jayson Jacoby. Bill Bradshaw, EO Media Group. December 4, 2023. Start with a swath of land more than twice as big as Rhode Island and Delaware.

Combined.

Carve a gorge deeper than the Grand Canyon and excise more than a dozen other rifts where major rivers flow.

Sculpt scores of peaks, more than 20 of which surpass 9,000 feet in elevation.

Cover much of this area with forests that are almost as diverse as the terrain. Stands of mature and second-growth ponderosa pine, Douglas fir and tamarack, thickets of juvenile lodgepole pine, alpine forests with whitebark pines that sprouted before Columbus sailed the seas yet are scarcely taller than a basketball hoop.

Distribute a series of meadows and sections of sagebrush steppe, and toss in a grassland that looks as though it ought to have bison grazing.

And now figure out how to manage these 5.5 million acres, all of which belong to every American, in a manner that reflects those who see in a thick ponderosa the boards that make up a home, and those who want the tree to stand for another century until nature takes it in a bolt of lightning or a gust of wind.

Consider all those factors and you’ll have a sense of the challenge facing U.S. Forest Service officials as they write new management plans for the three national forests in Oregon’s Blue Mountains.

The timeline perhaps explains best how daunting the task is.

The plans for the Umatilla, Wallowa-Whitman and Malheur national forests date to 1990. They were supposed to be replaced after about 15 years.

The Forest Service was already almost a decade behind that schedule when it released a draft version of new plans for each forest in 2014.

But after hearing complaints—from people who believed the plans allowed too little logging, livestock grazing and other uses and from others who argued that the proposals didn’t protect enough land from such uses—Forest Service officials withdrew the draft plans.

The agency released a final environmental impact statement for new plans in 2018, but that also prompted widespread concern about potential effects on how the forests are managed.

The Eastern Oregon Counties Association, which includes Baker, Grant, Union, Wallowa, Umatilla and Morrow counties, listed eight main objections: economics, access, pace and scale of restoration, grazing, fire, salvage logging, coordination among agencies and wildlife.

The Forest Service withdrew that proposal in March 2019.

Trying again

Now the revision process has started anew.

The first phase kicked off July 31, when the Forest Service published a notice in the Federal Register to start the assessment phase.

The agency held public open houses this summer to explain the process.

“Our next step is we’re going into the assessment phase, which is the current conditions of the forest,” said Michael Neuenschwander, the project leader for the revision process who reports to the three forest supervisors. “We will be bringing some materials to the public to be able to look at that.”

A draft version of the revised plans won’t be released until December 2024 at the earliest, he said.

The time required reflects both the complexity of the process and the importance of the national forests in the region’s culture and economy, said Eric Watrud, supervisor of the Umatilla, which is headquartered in Pendleton, Ore.

“The three Blue Mountain national forests really are national treasures, and they’re important to our communities from an economic point of view,” said Watrud. “They’re important from a recreation point of view. They provide important wildlife habitat, and cold and clean water that supports our fisheries and our communities.”

What’s a forest plan?

A forest plan is, in effect, an overview—a general assessment of the national forest and a broad description of the priorities for managing different parts of that forest.

“The forest plan is sort of the 30,000-foot level,” said Shaun McKinney, supervisor of the Wallowa-Whitman, which is headquartered in Baker City, Ore. “What parts of the forest may be focused on, say wilderness, which will be focused on recreation, which will be focused on timber management, those kinds of things.”

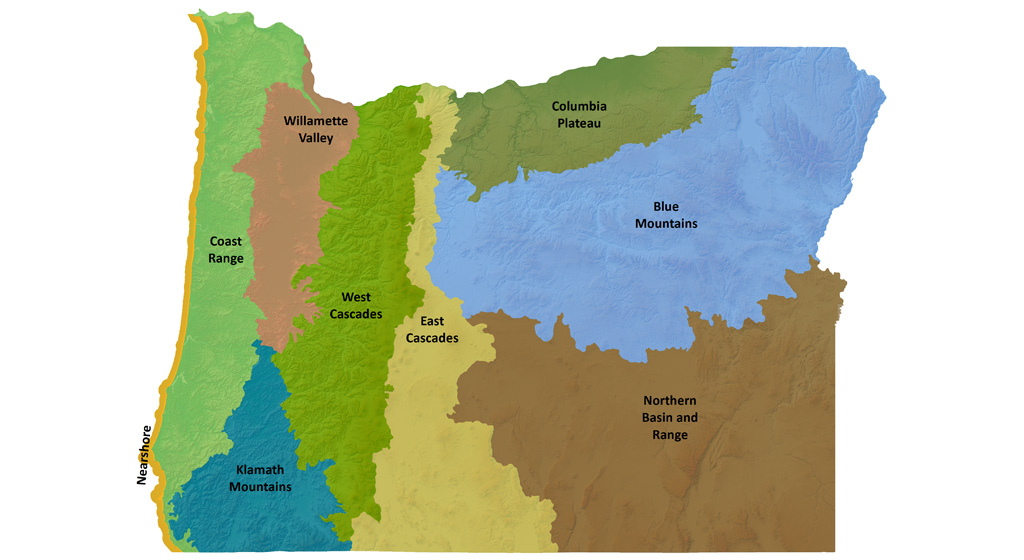

The Blue Mountains comprise one of nine state eco-regions recognized by the Oregon Conservation Strategy. Map: Oregon Conservation Strategy/ODFW

Forest plans do not include site-specific projects—such as timber sales, the approval of grazing or mining permits, the construction of a trail or campground or road. Those projects are proposed, studied and potentially approved through a separate process under the National Environmental Policy Act.

McKinney said a significant change from the Forest Service’s previous attempts to revise the plans for the Blue Mountain national forests is how the agency will deal with objections to the revised plans after they’re released.

In the past, he said, objections would be considered by Forest Service officials at the agency’s headquarters in Washington, D.C.

This time, each of the three forest supervisors will approve the plan, and objections will be sent to the Forest Service regional office in Portland.

Who’s writing the plans?

To draft the new plans, McKinney said the Forest Service is drawing on the expertise of its specialists in a range of disciplines including forestry, wildlife biology, cultural resources and wildfire, as well as some outside consultants.

Agency employees have been collecting data about each forest for many years, he said—what types of trees grow where, the roster of roads and trails and other recreation facilities, the extent of grazing allotments and areas permitted for mining.

Forest officials will use this information to draft several strategies for managing the forests. NEPA, the 1969 federal law, requires that agencies consider a range of alternatives.

These alternatives will be outlined in detail in the draft plans for each forest, and the Forest Service will solicit comments from the public about which alternative, or parts of alternatives, that residents prefer, or oppose.

“We definitely want the public’s engagement and input because there are going to be some folks that are going to be, you know, there’s plenty of wilderness, don’t want any more of that,” said McKinney. “And there will be other folks who say we want a ton more wilderness area. Public lands are everybody’s lands, which is wonderful. But everybody has an opinion.”

Forests are changing: Parts of the Blue Mountains—like this spot near Baker City—have experienced record-dry winters in recent years. Photo: Jayson Jacoby/Baker City Herald

Wallowa County Commissioner Susan Roberts said she wants the revised forest plans to put a priority on cutting timber and expanding livestock grazing, with a goal of reducing the amount of fuel in the forest and reducing the wildfire danger.

“What we don’t believe is there’s been appropriate management (of the forest) as a whole,” Roberts said. “They don’t manage it for the benefit of the health of the forest. That’s what we’re trying to change.”

Roberts’ fellow commissioner, Todd Nash, agrees.

Nash, who deals primarily with natural resource issues for Wallowa County, said the plans need to be updated.

“We’re operating off the 1990 plan so it’s pretty old,” Nash said. “Restrictions on grazing at the current time, to protect salmon and bull trout, have restricted a lot of grazers. We have a lot more closed than active grazing allotments.”

Nash is a rancher as well as president of the Oregon Cattlemen’s Association and sympathizes strongly with those in the cattle industry, a mainstay of the Wallowa County economy.

But he also sees a need for improved forest management for the timber industry in Wallowa County.

“The sustainable, long-term cuts took out the three mills that were in existence in 1990,” Nash said. “We can’t sustain a mill under what we’re currently doing. It’s had a tremendous effect on our forests. We need to make sure we set grazers up for success and we set loggers up for success.”

Baker County Commissioner Christina Witham is, like Roberts and Nash, a member of the Blues Intergovernmental Council. The Forest Service set up that group, which includes representatives from county, state, federal and tribal agencies, after the most recent forest plan revision was withdrawn in 2019.

The BIC tracks both the forest plan revision process and other issues related to the management of public lands in the Blue Mountains.

Witham said her top priority for the new forest plans comes down to a single word—“access.”

Witham said she means not only access by motor vehicles, but also access to the forest to thin overcrowded, fire-prone forests, open grazing allotments for local ranchers, and permits for miners.

Witham wants the Forest Service to increase the rate of forest thinning—including commercial logging—to reduce fuel loadings.

“What we have right now is mismanagement on a large scale,” she said. “The forest plan shouldn’t limit us, it should help us get to a healthier forest.”

McKinney said the new forest plans, like their current 1990 versions, will delineate areas where logging and grazing will be allowed and even emphasized as management tools.

Although the new plans will focus more on restoration than purely on logging volume targets, he said logs will continue to be a product.

Definitions of what constitutes restoration vary widely.

Emily Cain, executive director of the Greater Hells Canyon Council, said the organization’s members want to ensure that the forest plan revision is a “truly inclusive process.”

“The Forest Service has a challenging task,” said Cain. “Unfortunately, after several false starts, the agency doesn’t seem to be off to a much better start this time with the exclusive nature of the BIC process having, at the very least, the appearance of extractive interests jumping to the front of the line.

“Here, locally, and across the region, our members and supporters care deeply about our forests and communities. They, and we, expect the agency to start giving equal standing to all interests. It’s only through a truly inclusive process that the Forest Service will be able to develop a defensible and durable plan.”

Cain said the mature trees that remain in the Blue Mountains play vital roles in combating climate change, through their sequestration of carbon, as well as in providing habitat for wildlife.

“In recent years, exciting new science has reinforced much of what we all already know—that our region is of global importance,” said Cain. “Our intact forests are a critical connection between the Rockies and Cascades. Our headwater streams provide water for people, fish and wildlife all the way to the Pacific Ocean. In a changing world, these values are important on their own merits and also because protected public lands support healthy, vibrant communities.”

Cain said the Greater Hells Canyon Council wants new forest plans that are “guided by science, conservation values and just transitions to more sustainable economic models,” as well as “enforceable protections that are needed for the public lands that are so important to our way of life, and for future generations.”

Forests changes

McKinney said that in some places in the Blue Mountains the forests today are quite different from those of the past.

Some stands are overcrowded, and thus more vulnerable to insects, disease and fire, due to a combination of factors. These include excluding wildfires, which previously naturally thinned forests, and historical logging that removed the older, larger trees, such as ponderosa pines and tamaracks, but left firs that can form thickets of stunted, sickly trees.

“We’ve got a condition in some cases where we have overstocked stands, and we just really want to get those back into the historic range of variability,” McKinney said. “The plan will look at timber management, range management and trying to look for ways that we can identify those areas on the landscape that need to be treated, and that will result in fiber coming off the national forest.”

He said one difference from the past, including the 1970s and 1980s when the Blue Mountain national forests were producing hundreds of millions of board-feet of timber annually, primarily mature ponderosa pines and other species, is that today’s timber sales generally yield much smaller trees.

“I think logging is just as much a need out there,” McKinney said. “But the products coming out are different.”

Umatilla County Commissioner Dan Dorran, also a BIC member, touted the socioeconomic report the council crafted showing the economic harm from potential changes to forest management, including reducing vehicle access and reducing grazing and logging.

“Not just money, but livelihoods” are potentially at stake, Dorran said. “Whether it’s grazing, timber harvest, mill operator, you name it. It will affect a lot of people.”

In addition to the public opposition to previous iterations of the revised forest plans, a controversial issue related to two of the three forests is travel management.

The Umatilla has had a travel management plan for decades. Basically, the forest has maps that designate where motor vehicles are allowed, such as the Winom-Frazier trail complex near Ukiah.

By contrast, both the Wallowa-Whitman and Malheur, which account for more than half the national forest acreage in the Blue Mountains, are “open” forests, meaning motor vehicles are generally allowed except in designated closure areas.

The Forest Service has proposed a travel management plan for the Wallowa-Whitman, but in 2012, just a month or so after unveiling the plan, officials withdrew it. The reason was much the same as with the previous forest plan revisions—widespread complaints about how many miles of roads would have been off limits to motor vehicles.

McKinney emphasized the current forest plan revision process doesn’t involve travel management on the Wallowa-Whitman or Malheur forests.

“There’s a lot of interest in it, we know we need to do it,” said McKinney. “We just want to get this first piece done and we will work on the second piece. Travel management and access management will be a subsequent analysis and process not associated with the forest plan.”