Rather than conserve water, Golden Staters continue to hatch far-fetched schemes for importing it. They’re not going to stop anytime soon

Thirsty appeal: Named for an advocate of piping Northwest water to So Cal, Kenneth Hahn State Recreation Area has views across the dry L.A. Basin. Photo: CC/Flickr/T.Tseng

By John Harrison, October 13, 2022. Kenneth Hahn was an icon of progressive Los Angeles. Hahn, who died in 1997, was a member of the Los Angeles County Board of Supervisors for 40 years, 1952 to 1992, and before that a member of the Los Angeles City Council.

A state recreation area near Culver City is named in his honor. His obituary in the Los Angeles Times described Hahn as legendary. He championed major league baseball for the city, freeway callboxes, paramedics and civil rights.

He also advocated diverting a portion of the Columbia River to water-scarce Southern California at a time when the city faced withering drought, as it does today.

Several times in his illustrious career, perhaps more than several times, he unsuccessfully introduced resolutions calling for investigation of his diversion idea.

In May 1990, he wrote to then-Oregon Governor Neil Goldschmidt imploring him to “act like a good neighbor” and support diverting the Columbia.

Talk about walking into a running Oregon chainsaw.

“I have the distinct impression that you are trying to steal my water,” Goldschmidt responded in a letter to Hahn. “I don’t have enough water in the Columbia to raise the fish we need to rear, move the barges we are trying to move, generate the electricity that we all so badly need, irrigate the crops that need it, keep the native American tribes happy and then send some south to you.”

Goldschmidt ended with a curt, “hoping you’re not serious.”

None of those constraints has changed today. In fact, there are more constraints on Columbia River water today than in 1990—protecting threatened and endangered species of salmon and steelhead, for example—including in the estuary downstream of Bonneville Dam where Hahn’s pipeline would have started.

Save your stamps: Former Oregon Attorney General Dave Frohnmayer. Photo: University of Oregon

Oregon Attorney General Dave Frohnmayer also responded to Hahn, urging the supervisor to “save your stationery and postage. The rivers you would tap to slake the unquenchable thirst of Southern Californians happen to be major waterways of life and commerce in our area. Oregonians will not stand still for such a threat to this vital lifeline.”

Indeed.

There was public outrage, but also “can-you-believe it?” humor.

A Portland radio talk-show host asked his listeners what Oregon should accept in return for Columbia River water. The most popular answers: Disneyland and 60 days of California sunshine every year.

Covetous history

For decades, the Pacific Northwest has responded to and fended off efforts to divert its water, particularly from the Columbia River, to the Southwest, and particularly to California or Colorado.

These “inter-basin transfers” were proposed from Oregon, Washington, Alaska and British Columbia.

For example, in 1968 as Congress debated authorization of the Colorado River Basin Project, House Interior and Insular Affairs Committee Chairman Wayne Aspinall of Colorado said the authorizing bill would only initiate a series of studies by the Department of the Interior.

“Water is the lifeblood of this area, and unless new sources can be found, this thriving, prosperous, large segment of our Nation is, in my opinion, on a collision course with economic disaster,” said Aspinall.

Northwest members of Congress noted the veiled threat of “new sources,” to which Aspinall responded, “representatives of the Northwest felt that their area was the target of the studies for new sources of water. This, of course, is understandable, since water flow records on the Columbia River show that more than 10 times the average annual flow of the Colorado River empties unused into the Pacific Ocean each year.”

The word “unused” became something of a rallying cry for the diverters.

Later in his floor speech, published in the Congressional Record for May 1968, Aspinall as much as implied diversions would be needed.

“It is certain that no future water need in an area of origin [read: the Northwest] will ever be denied by reason of such diversion,” he said. What exactly was meant by “never be denied?” He didn’t explain.

Climate change will indeed result in regions eyeing other places’ resources, likely leading to legal, policy and other types of conflicts.

There were other proposals.

In 1991, a Canadian public relations consultant, Bill Clancey of Vancouver, and two private investors from Washington state, proposed to divert water from the North Thompson River west of Jasper, Alberta, in the Canadian Rockies to the Columbia River in British Columbia, and from there to California.

Clancey estimated the project would cost $3.8 billion, which probably is a fraction of what it actually would have cost considering planning, permitting, construction and the inevitable flood of litigation. The proposal never got traction. There was massive opposition, including among citizens and politicians in British Columbia and even from Clancey’s intended customer, the Metropolitan Water District of Southern California. Clancey died in 2003, and his dream of an international water transfer project died with him.

Also in 1991, the governor of Alaska, Walter Hickel, proposed a water pipeline from his state to California. Hickel’s proposal was quickly criticized for being too expensive, environmentally difficult and hopelessly optimistic.

Congress’s Office of Technology Assessment, defunded in 1995, reported in 1992 that a proposed pipeline down the Pacific Coast—essentially Kenneth Hahn’s idea—would not be as effective as water conservation, water banking and changing water pricing rules in California.

It added that if the water needs of the “entire arid West” were considered “a subsea pipeline to transport water from Alaska, diverting some water from the Columbia River, or various proposals for diverting water from Western Canada’s rivers, as well as other expensive options such as tankering water, might then be considered.” So far, at least, that hasn’t happened.

In 2012, the federal Bureau of Reclamation investigated various inter-basin transfer ideas including Hahn’s Pacific Coast pipeline, ocean tankers full of fresh water and even dragging icebergs from the Arctic.

None passed either the laugh test or, more importantly, the financial and political tests.

Idea that won’t die

California’s congressional delegation outnumbers the entire four-state Northwest delegation two-to-one, then and now. In response to what seemed to be credible threats to Northwest water, in the early 1980s the small but powerful Northwest delegation wrote into federal law a permanent statutory prohibition against diverting the Columbia.

This was followed by annual prohibition resolutions.

With Goldschmidt’s dismissal, the idea should have died, but it didn’t.

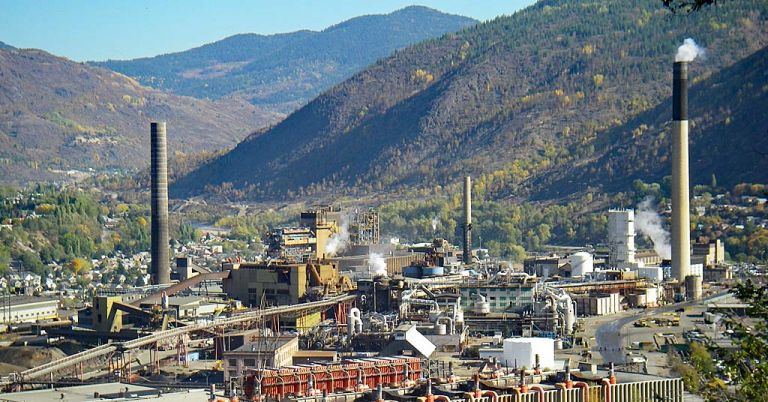

Moving the river: As water woes increase across the West, some states are looking north. Photo: Fotech

In April 2015, the San Diego Union newspaper editorialized that, in response to then-Governor Jerry Brown’s call for innovative solutions to address California’s drought, “the idea that intrigues us the most is a pipeline from the Columbia River.”

The editorial went on to acknowledge that a diversion would be politically, economically and legally difficult.

Then Captain Kirk teleported into the fray. In a speech, Star Trek star William Shatner proposed a Kickstarter campaign to raise $30 billion to fund a pipeline from Washington. Bill Monroe, a columnist for The Oregonian in Portland, wrote in response that “the beloved Captain Kirk’s phaser was set on stun.”

Once again, the idea should have died but didn’t.

The Fresno Bee newspaper editorialized in 2019—just three years ago—in support of “the incredibly simple solution” to the state’s water problems, which would be “to send south to California the abundant waters of the Columbia River.”

According to the newspaper, “only a lack of political will may defeat it”—no idle threat given the size of California’s congressional delegation.

And this summer, the Las Vegas Review-Journal published letters to the editor supporting a pipeline from the Columbia—or the Snake River—to the big Colorado River reservoirs that are once again plagued by drought.

In May, the newspaper had editorialized that California’s “green polices” meant the state will not acquire any more water, such as from the Northwest—implying, at least, that a pipeline from the Northwest would solve all problems.

How about conservation first?

Nothing about a diversion would be simple.

Consider 1). the multiple billions it would cost, 2). the innumerable permits that would be needed, 3). the challenges of engineering, financing and construction, 4). the impacts to Columbia and Snake river fish, both upriver and in the estuary, including more than a dozen species listed as threatened or endangered, 5). the inevitable massive amount of litigation, and 6). the unlikely acquiescence of Columbia River states, tribes, irrigators and municipalities to give up their rights to Columbia River water.

Daniel Rohlf, Professor of Law at Northwestern School of Law at Lewis & Clark College in Portland and also Of Counsel for the Earthrise Law Center, says it’s important to consider the source when thinking about the potential for a Columbia River diversion.

Practical solutions: Daniel Rohlf. Photo: Lewis & Clark College

“It is hard to take very seriously anyone’s complaints about water shortages anywhere in the West when we still grow enormous amounts of very thirsty—and extremely water-inefficient—crops like alfalfa,” he says. “We’re facing unprecedented water shortages and still pouring this precious resource on food for cows—amazing.

“So before we go geo-engineering the West Coast we should reform the dumbest ways we continue to use water.”

From a legal standpoint, Rohlf says federal law probably doesn’t have the final say in whether California could divert water from Oregon or Washington because federal law allows states to decide most questions of water allocation for diversions and consumptive uses.

“So good luck to California in attempting to get a right to divert water in Oregon or Washington and transfer it,” he says. “Unless California’s big, bad congressional delegation is willing and able to overturn a pillar of prior appropriation water rights in the West—the so-called McCarran Amendment—I don’t see much of any possibility that California diversion hopes have any realistic chance.”

And then there are other laws that certainly would come into play if a diversion were proposed—the Endangered Species Act and the National Environmental Policy Act, for example.

“I don’t see how any diversion to California could avoid triggering federal jurisdiction somehow, so both NEPA and the ESA would come into play,” Rohlf says. “I’d love to see the Environmental Impact Statement for a diversion to California.

“And with 13 listed evolutionarily significant units of salmon and steelhead transiting and depending on the lower river and estuary, I think it would be tough to avoid a jeopardy Biological Opinion for a diversion scheme.”

Time to get real

So far, at least, new ideas for diverting Columbia River water to California don’t appear to have generated interest outside of certain news media.

“The state of California is not considering diverting water from the Columbia,” says Ailene Voisin, information officer for California’s State Water Resources Control Board. “The topic always comes up during times of drought, but again, I am told nothing has changed on our end.”

“It was an avenue that was looked into in decades past, and due to the significant environmental impacts, interstate water rights, along with other complications, it culminated in a decision to not pursue the project,” says Mia Rose Wong, a spokesperson for the Los Angeles Department of Water and Power.

Likewise, Elliot Mainzer, president and chief executive officer of the California Independent System Operator, told Clearing Up in an email, “I think I can safely say that that idea has not resurfaced in recent years” outside of hopeful editorials.

In fact, California has a much better solution, the one derided as green policies by the Las Vegas newspaper. This is Governor Gavin Newsom’s $8 billion strategy to reinforce California’s dwindling water supply, unveiled in August.

“The science and the data lead us to now understand that we will lose 10% of our water supply by 2040,” Newson said in discussing the strategy. “As a consequence of that deeper understanding, we have a renewed sense of urgency to address this issue head on.”

And his strategy does just that, through water recycling and desalination, capturing and saving more stormwater both above ground and below, reducing water use in cities and on farms by improving water-use efficiency, improving all water management actions and reusing at least 800,000 acre-feet of water per year by 2030 and 1.8 million acre-feet by 2040.

Most of the reused water will come from recycling wastewater discharges that are now going into the ocean.

If this sounds a bit familiar, it’s more or less what Congress’s Office of Technology Assessment recommended for California’s ongoing water crises back in 1995.

Unremitting need

Despite the pragmatism and prescience of California’s drought resilience strategy, threats to Pacific Northwest water very likely could continue, as the Office of Technology Assessment hinted in its 1995 report.

“Climate change will indeed result in regions eyeing other places’ resources, and will likely lead to legal, policy and maybe even other types of conflicts. But at least in the next couple of decades, I see pretty slim chances for any big water pipeline from the Northwest to California,” says Rohlf.

Diverting the Columbia or Snake is a bad idea, it’s always been a bad idea and it will never be a good idea.

It would be impractical, cost billions, launch hundreds of lawsuits and take years, if not decades, to even study. There’s not enough time.

Climate change is now driving decisions about water conservation throughout the West—or should be. What’s needed are innovative, climate-driven and practical responses to the perils of drought, like Governor Newsom’s strategy.

Increasing California’s water supply by decreasing it elsewhere is not the right solution.

We went through this many years ago and now we have the Californians moving here for the green and clean air. No way do we let them take our water.

Kate and Ron, the western drought, changing climate, and increasing population mean that pressure on water will be coming from all over.

makes sense tunneling technology is as reliable as it has ever been The upper eastern columbia river basin has ample rain fall and surplus water to boot the tunneling machines can dig and line tunnels up to 35 feet in diameter a mile a day and the materials removed would team with usable rocks and minerals …once your into the final canyons turn the water lodse gravity does the rest…death valley would create a 5 and 6th great lake evaporative cycles would cover down for 7 dry states…increasing usable tillable lands to an additional portion of 1/3 usable land in the usa…increasing value to all…to bad world war 2 stopped the government the first time….Jobs and resources for all not disturbing the sparse populations in the dry states instead of fighting fires we could be planting crops…the natural mountain ranges would keep the waters in the driest regions …it took 10,000 years from the last ice age to dry the regions this is doing the same things…water is a good thing

The Columbia River dumps 4 to 5 times more fresh water ? into the Pacific Ocean than California uses in an entire year at 264,900 ft³/second (1,981,452 gallons per second, or 62,487,070,272,000 gallons , 191,765,777 acre feet, an equivalent of 1/2 of Lake Erie).

California uses 42 million acre feet(an equivalent of a little more than 2 Lake Meads) of water annually, or only 22% of the Columbia River outflow.

Just 5% (9.6 million acre feet) of the Pacific outflow of Columbia River would supply 22% of California’s total water supply.

By comparison, the California Aqueduct can deliver a maximum of 4.1 million acre-feet of water.

The US 361 million acre feet of water total per year for all uses. California uses 11.6% of that total water use. The Columbia River dumps an equivalent of 53% of the total US fresh water usage into the salty Pacific.

Giving the waters of the Columbia to California would be like loaning money to a gambler, or asking an alcoholic to mind your liquor cabinet. We all know that this “emergency” water would not go toward conservation projects or existing uses or refilling reservoirs; it would be used to grow California into ever-larger water needs, with new projects, new housing developments, and new bottling plants. It is obvious that the state has to cut back. Thirsty crops like almonds and alfalfa have to be cut off. Water rights need to be re-evaluated. If someone’s business model is “other people must donate their own resources, which I will not pay to deliver” then the business deserves to go under. You don’t fix a leaky bucket by pouring more water into it; you plug the hole first. Yes, California provides a lot of crops for the nation; but maybe those crops should be planted where the water is.

CA Contributes 14% of the U.S GDP more by far than any other state and because of this it benefits all Americans to keep the state supplied with water in a cost effective way that would not imposed an economic, environmental, or quality of life hardship to Oregon….

Shut down almond growers giant corp in Cali… problem solved

I’m not understanding. As initially discussed, some 30+years ago. Divert more water from canadian rivers, that also dump excess into the ocean, to the columbia river. Such that none of the current down stream initiatives, aquatic needs are impacted negatively by a diversion to California.

Simply add what California needs to the columbia river, so that no one is worse off.