Suggested revisions to the 30-year-old Northwest Forest Plan include a call for more cutting in northern spotted owl habitat

Up for discussion? Old growth in Oregon. Photo: Matt Betts

By Kendra Chamberlain. July 31, 2024. (Revised Aug. 13, 2024.) A federal committee of logging stakeholders, tribal representatives, conservationists and experts have released a suite of recommendations to the Northwest Forest Plan, a sweeping U.S. Forest Service management policy covering 8 million hectares of federal forest lands.

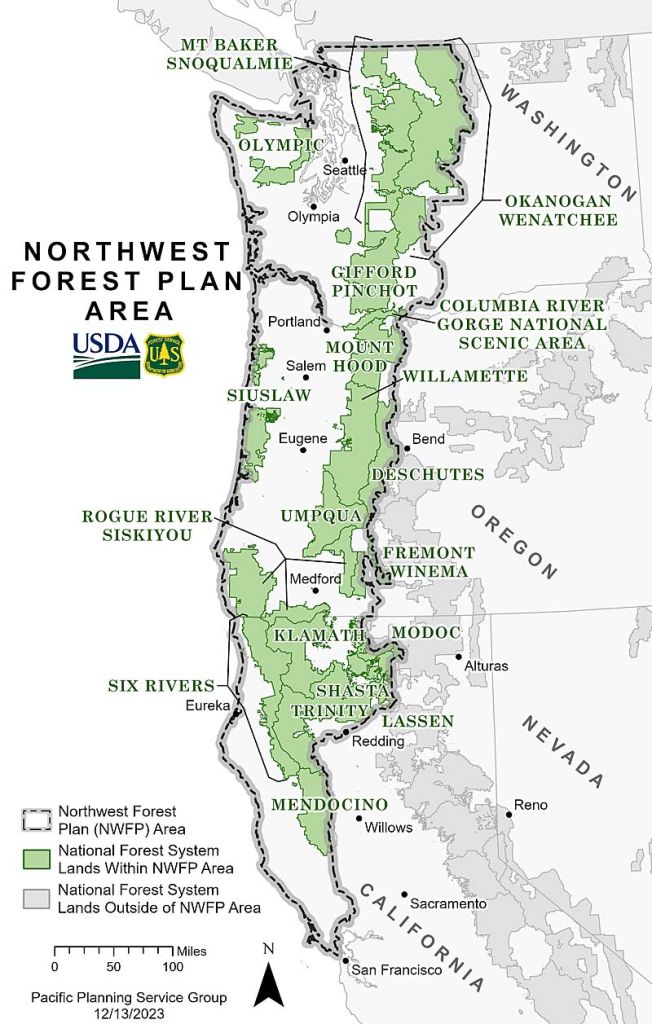

Adopted in 1994, the Northwest Forest Plan (NWFP) sets the overall management direction and guidance for 17 national forests across 24 million acres of federally managed lands in western Oregon and Washington and northwestern California.

The new recommendations range from increasing tribal participation in managing lands to managing forests for carbon sequestration and climate change—goals that weren’t top of mind to forest managers in the 1990s.

According to committee member Jerry Franklin, professor emeritus of environmental and forest sciences at the University of Washington’s College of the Environment, the committee “thought separately about two types of forests.”

Those two types of forest are “dry” forests on the east side of the Cascades Range, typified by species such as ponderosa pine and western larch, and “moist” forests on the west side, typified by Douglas fir and western hemlock.

Due in part to increasing concerns about wildfire, “those two types of forests have to have very different types of forest management plans,” said Franklin.

The east side forests, for example, require more active management.

“On the dry side you need a major program to restore forests to a condition that fire can be tolerated,” he said. “The committee recommended correcting the failure of the [initial] Northwest Forest Plan to encourage the restoration of dry forests … to make restoration of these forests a priority before they all burn up.”

The recommendations call for opening up some protected mature and old-growth areas for logging for the first time in 30 years.

This has conservationists concerned.

“It’s pretty clear that the Forest Service has a specific goal to amend the Northwest Forest Plan to give itself more explicit discretion and authority to accelerate logging, including in mature and older stands. And these committee recommendations ultimately reflect that,” says John Persell, a staff attorney at Oregon Wild.

Franklin disagrees with this assessment, noting that “thinning” practices will primarily remove younger trees living within older stands.

“The goal is to restore these forests to be more resilient to fire. We’re going to do that with tree cutting, thinning and we’re going to do it with fire,” he said. “If the Forest Service does it the right way, most mature and all old trees will remain in restored stands.”

According to Franklin, in “dry” forests trees reach maturity at about 150 years, while old trees are at least 200 years old. In “moist” area, forests mature at about 100 years and become old at 200 years.

30 years of a plan

The Northwest Forest Plan was born out of an attempt to save the northern spotted owl.

It pivoted forest management priorities in the Pacific Northwest from essentially treating woodlands as timber factories to understanding them as reserves for threatened and endangered species, including salmon and the marbled murrelet.

According to some estimates, the NWFP resulted in a 90% reduction in timber harvest virtually overnight.

Map: USFS

But measuring impacts of the plan 30 years later isn’t easy, according to retired Oregon State University professor Norm Johnson.

Johnson was one of the “Gang of Four” group of experts that hammered out the original plan under President Bill Clinton.

On the one hand, old-growth forests on the western side of the Cascades Range were saved from logging, says Johnson.

But northern spotted owl populations have continued to decline.

The marbled murrelet population has remained about the same size, says Johnson. Salmon habitat has improved under the plan, he says, but salmon populations haven’t rebounded for reasons beyond the USFS’s control.

And, he adds, the plan wasn’t a success in protecting the older forests in the dry areas east of the Cascades—those forests are too vulnerable to wildfire.

Assessing the recommendations

The federal committee’s recommendations tweak protections for both mature and old-growth tree stands in both the wet and dry sides of the Cascades Range.

While the original plan protected tree stands that were 80 years or older, the current recommendations bump that age up to 120 years, opening up about 15% more mature forest for logging.

The recommendations also allow salvage logging in old-growth forests after they’ve been disturbed by fire, something the original plan didn’t allow, and which critics say inhibits natural forest recovery following a fire.

Perhaps most starkly, the recommendations abandon the idea of protecting old-growth stands altogether in the dry forests of the eastern and southern portions of the management area.

Instead, the recommendations aim to protect the oldest trees in those stands by thinning out younger trees.

“Those stands are uncharacteristically dense. Fire suppression has really changed those stands—they’re in what you can almost call an unnatural condition,” says Johnson.

But there’s a big caveat to opening up those dry forest areas to more logging.

“Unfortunately, those overly dense stands are good owl habitat,” says Johnson. “So there we are. What a conundrum. There’s a lot to be worked out there.”

Oregon Wild’s Persell doesn’t believe there’s a good reason to open up mature or old-growth forest stands to increased logging.

“The science supporting the retention and recruitment of more old-growth forests to make up for the deficit of what we’ve lost has only solidified in the 30 years since the Northwest Forest Plan was first adopted. We’ve got ongoing biodiversity and climate crises that these mature, old-growth stands offer a natural solution to,” says Persell. “The northern spotted owl needs as much suitable habitat, intact and available, as possible.

“I look at these recommendations and I don’t see them as supporting spotted owl populations because we’re going to end up with less spotted owl habitat, not more.”

Johnson seems more optimistic about the recommendations.

“Let me say this, and I’ve got my hand on top of their report,” says Johnson. “The fact that a fairly broad group could come together and agree on a number of changes that should be made is a major accomplishment. It’s a big deal to do this.”

Another accomplishment touted by committee members is a recommendation that hundreds of thousands of acres of moist mature and old forest be removed from availability for timber harvest.

“That will be a huge win if the Forest Service accepts the recommendation,” said Franklin.

Critics, however, say that while the forests in question were technically not protected under the 1994 plan, they’re neither being logged nor are under any threat of being logged, and therefore represent a minimal compromise.

It remains to be seen how the USFS will incorporate the extensive list of recommendations into the plan.

The agency will release its final amendment to the NWFP this fall.

Really looking forward to the NWFP amendment and all. Keep us posted!!

Johnson touched on this, but fires were restricted from all forests for 100 years resulting in unnatural dense small tree stands surrounding old growth. When fire comes the young highly flammable trees will carry the fire into the crowns of the old growth potentially killing them. That’s what happened on the California’s Inyo mountains where fire killed old growth giant sequia trees.

I believe we can thin dense small trees, then use prescribed fire creating old growth stands that are more fire resilient. Doing this would actually protect spotted owl habitat by protecting old growth from burning up.

The withholding of fire was a human action, not natural. I feel we need to use human actions now to get old growth stands to a more natural condition to withstand fire.

These recommendations are based on my experience in ecological forestry and wildfire