But advocates call new federal guidelines for chemicals used in tires an important step in ending “urban stream syndrome”

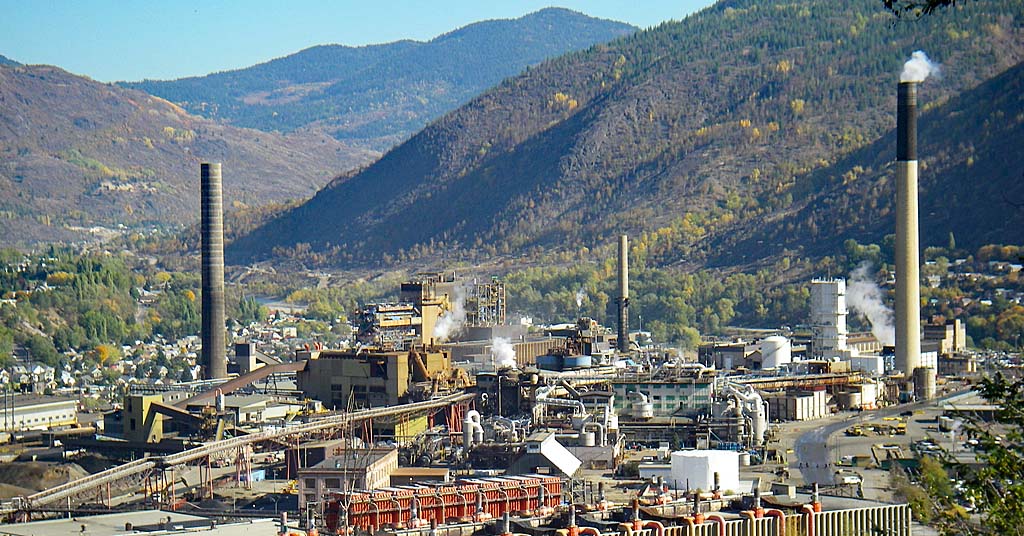

Snail’s pace: All those tires are shedding chemicals. Governments are taking notice. Slowly. Photo: Tony Webster/Flickr

By Kendra Chamberlain. June 20, 2024. Years after a breakthrough 2020 study linked mysterious coho salmon die-offs to a ubiquitous tire chemical, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency took its first step in addressing the contaminant—sort of.

Earlier this month, the EPA finalized screening values for the chemical 6PPD and one of the components it breaks down into, 6PPD-q.

The “aquatic life screening value” is a voluntary and non-enforceable standard of exposure that states and Tribes can use in their own water quality programs.

It sets rough parameters for lethal limits of exposure to the chemical for aquatic life, but has no teeth in terms of enforcement.

Endangered species of salmon, particularly coho salmon, experience massive mortality events when entering urban areas.

Stumped researchers dubbed this “urban stream syndrome” and “urban runoff mortality syndrome.”

For decades, no one knew what exactly was causing the deaths, but many suspected that a chemical found in cities was making its way into waterways.

Researchers at Washington State University finally pinpointed the culprit in 2020 as the chemical known as 6PPD, which breaks down into 6PPD-q when exposed to ozone.

The chemical has been used since the 1950s to help protect rubber used in tires, and tends to degrade into “tire dust” on roadways. Those particles then wash into waterways through storm water runoff.

The study received widespread national media attention, including in a June 2023 story in Columbia Insight.

But with just a few years of research on 6PPD-q, the EPA says there simply isn’t enough data available to establish precise regulatory limits for the chemical.

The aquatic life screening value offers a baseline that enables state and federal agencies to get on the same page while awaiting more research.

One small step

While there’s no enforcement mechanism associated with the exposure standard, it’s an important first step to better understanding and regulating 6PPD-q in the environment, according to Dr. Alan Kolok, professor of ecotoxicology at th University of Idaho.

Kolok does toxicological work in the Columbia River Basin.

“It’s definitely something that we should be praising,” Kolok told Columbia Insight. “It really is just a step in the process—it’s a really important step in the process—but it’s a step in a process of ratcheting down our understanding based upon the information available.”

Alan Kolok. Photo: University of Idaho

Salmon advocates say the end goal is to stop using the chemical entirely in tire manufacturing, but first manufacturers need to find an alternative.

Tire makers say removing the chemical without replacing it would cause tires to degrade much faster, increasing safety concerns and ultimately sending more tires to the landfill.

In 2023, the Center for Biological Diversity issued a notice of intent to sue the federal and California Departments of Transportation (Caltrans), the Oregon Division of the Federal Highway Administration, the National Marine Fisheries Service (NOAA) and the Secretary of Commerce for violations of the Endangered Species Act. That same year, The Institute for Fisheries Resources (IFR) and the Pacific Coast Federation of Fishermen’s Associations (PCFFA) filed suit against U.S. tire manufacturers over the use of the chemical.

In the meantime, state governments are tackling the problem in their own ways.

Washington is working on solutions for filtering out the chemical from urban water runoff, while California is requiring tire manufacturers to look to alternatives to the chemical if they want to sell tires in the state.

Emily Jeffers, senior attorney at the Center for Biological Diversity, agrees with Kolok that the screening value is a good start, but says more needs to be done.

“What we really need are enforceable water quality criteria that will lead to real limitations on this toxic chemical in our waterways,” Jeffers told Columbia Insight in an email. “Ultimately, a ban on 6PPD is the only way to truly protect salmon and other critters.”