A giant toxic mess on the Canadian border may finally be getting national attention. Not everyone is happy about that

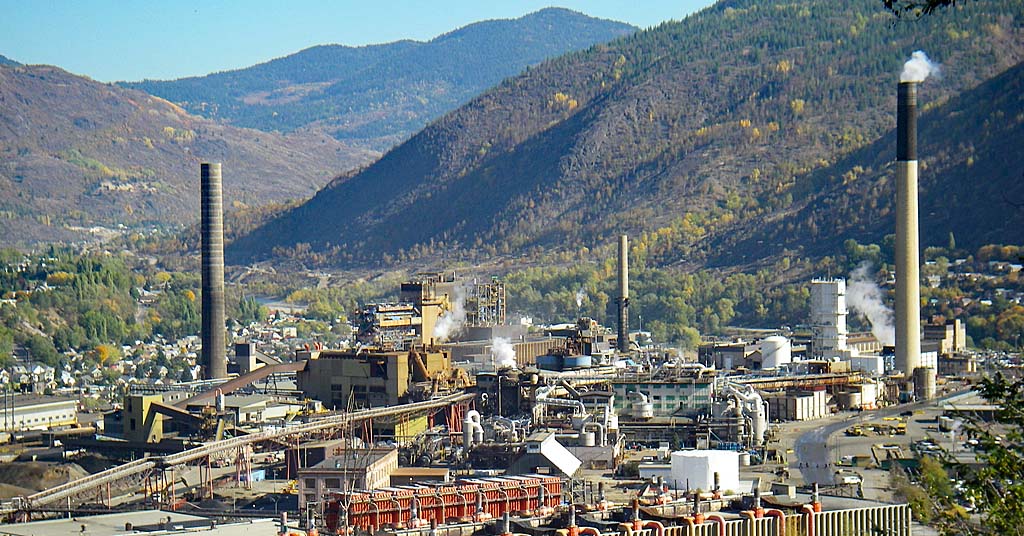

Big dumper: Less than 10 miles across the international border in Trail, B.C., the Teck Resources smelter on the banks of the Columbia River is the main source of metals contamination in the upper Columbia River Valley. Photo: Washington DOE

UPDATE: On March 5, 2024, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency announced a proposal to add the Upper Columbia River Site in northeast Washington to the National Priorities List, the list of hazardous waste sites in the United States eligible for cleanup under the federal Superfund Program. In a press release announcing the decision, the EPA said “the agency has determined that soils contaminated with lead and arsenic pose unacceptable risk to residents at affected properties, particularly to children.” —Editor

By K.C. Mehaffey. February 22, 2024. More than two decades after the Environmental Protection Agency found that a 150-mile-long reservoir in the upper Columbia River is eligible for the National Priorities List, the agency is, once again, considering whether to formally propose making it a Superfund site.

As confirmed by a federal judge in 2012, the Canadian mining company Teck Cominco Metals, Ltd. dumped almost 10 million tons of toxic slag into the Columbia River over a period of 90 years.

In that 2012 ruling, U.S. District Judge Lonny Suko found that Teck had intentionally dumped heavy metals into the Columbia River, and that company officials knew their actions would likely cause harm. He noted that even after the state of Washington and the EPA started pressuring the company to stop dumping slag into the river in the early 1990s, it did not.

“Profits were ‘excellent’—$100 million per year—and it continued to discard slag at a rate of 400 tons per day,” he wrote.

Teck only stopped dumping wastes into the river in 1995, after the Canadian government investigated and required the company to stop.

The disposals came from its smelter in Trail, B.C., about 10 miles north of the Canadian border with the northeastern corner of Washington. (The smelter is still operating, though no longer dumping pollutants into the river.)

Heavy metals—including lead, zinc and mercury—traveled downstream into U.S. waters.

Much of it settled in the Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area and along the shores of this manmade lake created by the Grand Coulee Dam.

The judge ruled that the company—now Teck Resources, Ltd.—is liable under U.S. law to pay for studies examining the extent of the pollution from its releases into the Columbia River, and to help clean it up.

Just south of the border, residents in and around Northport, Wash. in Stevens County, have been grappling with lead- and arsenic-contaminated soil. They’re advised to keep their children from playing in it, take off their shoes and wipe their pets’ paws when going indoors and moisten the soil and wear garden gloves when working in it.

The contaminated soil is from airborne emissions. The 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals held that Teck is not liable for those cleanup costs.

Washington’s Stevens County in red. Map: Wikimedia Commons

Elsewhere, one beach along the lake’s 600-mile shoreline has been closed for more than a decade due to elevated toxins, and Teck paid to have the sand at another beach removed and replaced.

But despite decades of studies, little cleanup work has been done along Lake Roosevelt’s shores and nothing has been done in the reservoir itself, which stretches from Grand Coulee Dam to the Canadian border.

Now, the EPA is considering—once again—whether to propose adding this 77,000-acre site to the National Priorities List, which could help the agency access funding for cleanup.

Congress created the National Priorities List—or Superfund—under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, or CERCLA, in 1980.

The law gives the EPA broad authority to require responsible entities to clean up hazardous waste sites. It also taxes chemical and petroleum industries to help fund the cleanup of sites when no responsible party can be identified.

In the Upper Columbia River, Teck could be held liable for cleanup related to its history of dumping slag into the Columbia River, while a Superfund listing would help provide funds to clean up contamination related to airborne emissions that resulted in soil contamination.

A decision could come later this month.

County officials oppose Superfund designation

Lake Roosevelt is a massive body of water. Covering 125 square miles, it’s surrounded by wide-open spaces and largely undeveloped shorelines. Two Indian reservations and four Washington counties touch its shores.

The Lake Roosevelt National Recreation Area attracts some 1.5 million visitors every year.

Those visitors—and whether they will keep coming to a Superfund site—are just one of the reasons county commissioners from the area say it’s too soon for a Superfund listing.

A Jan. 16 letter to EPA from the Eastern Washington Council of Governments—which includes 16 counties—urges the agency to wait for a completed remedial investigation and feasibility study (RI/FS) before considering a Superfund listing.

The RI/FS studies will help the EPA determine a course of action for cleanup.

Water feature: Created by the Grand Coulee Dam on the upper Columbia River, Lake Roosevelt is a summer magnet for recreationalists. Photo: NPS

Lincoln County commissioners argue that few contamination issues have been found in the southern portion of the reservoir, and they’d like to work with the EPA on alternatives to a Superfund listing to address issues in the lower reservoir.

In Stevens County—where Northport is located—commissioners threatened legal action if the EPA moves ahead with a listing before completing the studies, which have been underway since 2006 and could be complete as soon as this year.

In addition to chasing away tourists, commissioners say designating the area as a Superfund site would cause property values to plummet and devastate local businesses.

The commissioners also contend that a listing could threaten Washington’s agriculture industry. They say foreign countries may conclude that the thousands of acres of wheat, potatoes, apples, cherries and other crops irrigated by Columbia River water have been contaminated, despite evidence to the contrary.

“If buyers question the safety of these foods, they could stop trade and markets may not recover for decades,” the commissioners wrote in a letter to Wash. Gov. Jay Inslee.

Their letter also said the Northeast Tri-County Health District has conducted tests for lead in Northport children more than once and concluded children don’t have elevated lead levels in their blood.

But Washington Gov. Jay Inslee and two Tribes—the Confederated Tribes of the Colville Reservation and the Spokane Tribe of Indians—wrote letters to the EPA strongly supporting the Superfund designation.

Colville tribal leaders have repeatedly said they want Lake Roosevelt cleaned up, and a Superfund designation would bring the level of priority and funding needed to do it.

Tribal issues

It was the Colville Tribes that, in 1999, initially raised the issue of contamination in Lake Roosevelt, petitioning the EPA to conduct an assessment.

That assessment, and Teck’s refusal to conduct the RI/FS, prompted the EPA to order Teck’s compliance.

After Teck failed to comply with the order, two Colville tribal members sued the company in 2004 to force compliance under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, or CERCLA.

The state of Washington joined the case, supporting the Tribes.

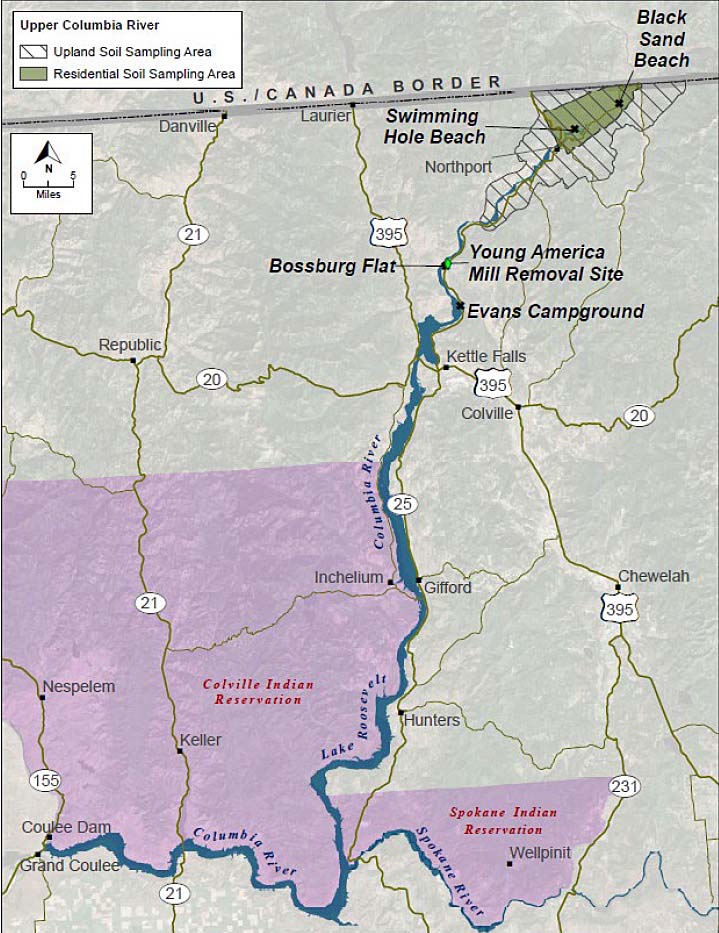

Columbia River above the Grand Coulee Dam. The soil sampling areas are being considered for a new Superfund site. Map: EPA

Teck claimed that CERCLA didn’t apply to companies in Canada, but a U.S. District Court judge disagreed, and in 2006, a 9th U.S. Circuit Court of Appeals affirmed the lower court’s ruling.

But earlier that year, the EPA entered into a settlement agreement with Teck, giving the company the task of completing the RI/FS under EPA oversight—a move the Washington State Attorney General’s Office called unusual.

“The agreement limited state and tribal ability to participate fully in the cleanup process,” according to a news release from Attorney General Rob McKenna.

The Colville Tribe was later awarded nearly $8.3 million for expenses related to the case.

But all the legal activity did little to resolve the problem of heavy metals and other chemicals in and around Lake Roosevelt.

“Widespread contamination at the UCR Site and adjoining uplands continue to pose risks to human health, disproportionately impacting low-income and Tribal residents, and risks to the environment,” Inslee wrote in his letter of support to the EPA. “Despite longstanding evidence of the contamination and its associated risks, only very limited progress on site investigation and cleanup has occurred to date.”

Inslee pointed out that the EPA’s authority to require comprehensive and timely investigation under its 2006 settlement agreement with Teck is limited, with no provisions requiring any actual cleanup.

“The legacy of contamination, ongoing adverse impacts to human health and the environment, delayed cleanup actions, and budgetary constraints imposed by the Settlement Agreement justify adding the Site to the NPL,” the letter stated. “Without Superfund monies, only limited funding options will be available to address the unacceptable risks and cleanup requirements identified in the forthcoming cleanup plan.”

A listing would help the EPA develop a plan for comprehensive and timely cleanup, access to federal funding and exert greater control over Teck’s cleanup activities and a mechanism for cost recovery.

Decision time

Andy Dunau is the executive director of the Lake Roosevelt Forum, a nonprofit organization that brings together the interests of two Tribes, federal and state agencies, and four counties—each with their own ideas about how the lake should be managed.

Through the forum’s newsletters, Dunau has been reporting on the EPA’s upcoming decision on whether to propose a Superfund listing.

A listing would begin with a notice in the Federal Register to open a public comment period.

After receiving and reviewing those comments, EPA would decide whether the site belongs on its Superfund list.

It may happen this month, it may happen in September, or it may never happen, he says.

But the EPA has been preparing the community and meeting with local, state and federal politicians about a possible proposal for listing as soon as this month.

Game changer: The Grand Coulee Dam is the largest hydropower producer in the United States and one of the largest concrete structures in the world. It created Lake Roosevelt. Photo: Town of Grand Coulee Dam

Dunau says he understands the concerns of county commissioners and the impact that a listing could have on the local economy. But he also sees the frustration of the state and Tribes who’ve seen so little cleanup over so many years.

“I’m not here to pick sides,” he tells Columbia Insight.

Regardless of the decision about the Superfund listing, Dunau says his bigger concern is keeping the community engaged, and their expectations manageable.

“It’s very difficult to work with and manage community expectations when something’s been going on for 20 years,” he says. “The sad thing is, a lot of the community has tuned out. It’s just gone on for so long, they either don’t expect much to happen, or they don’t believe there’s a problem.”

Many locals seem to believe that if the contamination was serious it would have been cleaned up by now, he says.

Dunau says once the RI/FS studies are complete, the EPA will determine what cleanup will be required and issue a record of decision that will include how much of the cost Teck will be expected to cover.

In a statement to Columbia Insight, Teck says it remains committed to completing the ongoing RI/FS under the EPA’s oversight to evaluate potential risks associated with its historic operations at Trail.

“Over the last 17 years, we have spent over US$180 million on studies of the Upper Columbia River, including sampling of water, fish, beaches, sediments, soils, and plants. To date, those studies indicate that the water is clean, the fish are as safe to eat as other fish in the Pacific Northwest, and, with one exception unrelated to the Teck Trail facility’s operations, the beaches are safe for recreation,” the Teck statement says.

Evaluating health risks

So how serious is the contamination?

A human health risk assessment completed in 2021 by the EPA found that soils in and around Northport pose potential risks to residents in some areas.

The EPA says it has completed several rounds of cleanup on properties with the greatest contamination and health risk.

“To date EPA has cleaned up 59 residential and common use properties in Northport, and Teck has cleaned up 18 additional properties and one Tribal allotment,” the agency says.

More than 150 residential properties could be eligible for cleanup in the future.

Alone for now: Bradford Island at the Bonneville Dam, 40 miles east of Portland, is currently the only Superfund site on the Columbia River. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers used the island as a toxic waste dump for decades. Screenshot: Columbia Riverkeeper

The Washington Department of Ecology says the cleanup of properties in the Northport area will require the removal of more than 7,000 tons of contaminated soils.

Soil sampling in 2014 and 2015 found the average lead concentration at the properties was four times higher than federal cleanup standards. The maximum concentration was about eight times higher.

“These investigations resulted in EPA’s Region 10 Seattle office issuing a time-critical removal Action Memorandum to address the exposure threats at these properties,” according to the Washington State Department of Ecology website.

According to the EPA, “Lead in residential soil is the primary concern for people’s health and the environment.”

Exposure to lead is especially dangerous for children under six years because their growing bodies and brains absorb more lead.

The EPA recently released new recommendations for lead-contaminated soil, noting that “Very low levels of lead in children’s blood have been linked to adverse effects on intellect, concentration, and academic achievement.”

The Lake Roosevelt Forum’s 2020 Public Guide on human health risk assessments for people who visit and live near Lake Roosevelt offers numerous precautionary measures for people who may contact soil that could be contaminated with lead and other metals.

The guide says the Upper Columbia Valley area includes about 100 square miles—or 64,000 acres—east and west of the Columbia River from the Canadian border to about 40 miles downstream.

“In the Valley, exposure to lead in soils is a concern,” reads the guide. “This is primarily due to smelter air emissions linked to air deposition of lead that contaminated the surface soil.”

Gardners are advised to grow vegetables in raised beds with clean soil. Property owners are told to cover bare patches of dirt with bark, sod or decking. And residents are encouraged to frequently wipe down dust, scrub their childrens’ toys and thoroughly wash their hands and face after working outside.

10 million tons of slag

Contaminants that settled to the bottom of the reservoir appear to be causing fewer human health issues compared to the heavy metals released through smokestacks that traveled through the air and settled on the land.

Based on sampling of fish caught in the lake, a fish consumption advisory recommends against eating any northern pikeminnow, and limiting intake of large-scale suckers and largemouth bass to a few servings a month due to concentrations of mercury and PCBs.

Kokanee, lake whitefish, rainbow trout, white sturgeon and northern pike are considered a “healthy choice” when limited to seven servings per week for men and older women, and two or three servings for children and women of child-bearing age.

Fish including burbot, longnose suckers, mountain whitefish, smallmouth bass and walleye should be limited to one to three servings per week.

Threat level: Northern pike were first noticed in Lake Roosevelt in 2011. The invasive species has the potential to upset billions of dollars of investment to rebuild native fish populations. Photo: Northwest Power and Conservation Council

The forum guide notes that sand at 33 public beaches was sampled and only Bossburg Flats Beach—on federal land—exceeds human health criteria for recreation due to lead.

The beach is located about 15 miles north of Kettle Falls, and the National Park Service closed it in 2012.

The EPA says it’s also safe to swim in—and even ingest—Lake Roosevelt’s surface water.

Although the agency recommends against drinking it, surface water sampling found the water meets all federal drinking water standards.

“EPA did not specifically evaluate surface water for irrigation or agricultural uses, but because the water meets drinking water standards, we would not expect these uses to pose risks,” it says.

In December, the EPA completed its final baseline ecological risk assessment for upland terrestrial habitat, which evaluates the risks to plants and wildlife exposed to the metals and chemicals.

“The assessment concluded that concentrations of nine metals pose unacceptable risks to plants, invertebrates, mammals, and birds exposed to soil in the upland area,” says the EPA.

Cadmium, lead and zinc present the greatest and most widespread risk to plants and animals in the area, it says.

According to the EPA, Teck submitted a dispute to these findings in January, and the agency is currently in discussions with the company over its concerns.

The EPA is also conducting an aquatic species risk assessment, which it expects to complete this year.

But more than the outcome of these studies, the focus has turned to EPA’s next National Priorities List—which usually comes out in February and September—to see if the upper Columbia River study area will be part of its proposal.

Today I hope the BC Budget addresses the environmental issues from Trail operations

I am interested to see what happens with this issue. Also, I did not know there is a super fund site near Bonneville. As usual I depend on Columbia Insight to educate me about so many local environmental I’ve been unaware of. Thank you–