Oregon is faring better than Washington and Idaho, but record lows will put irrigators in a tough spot come spring

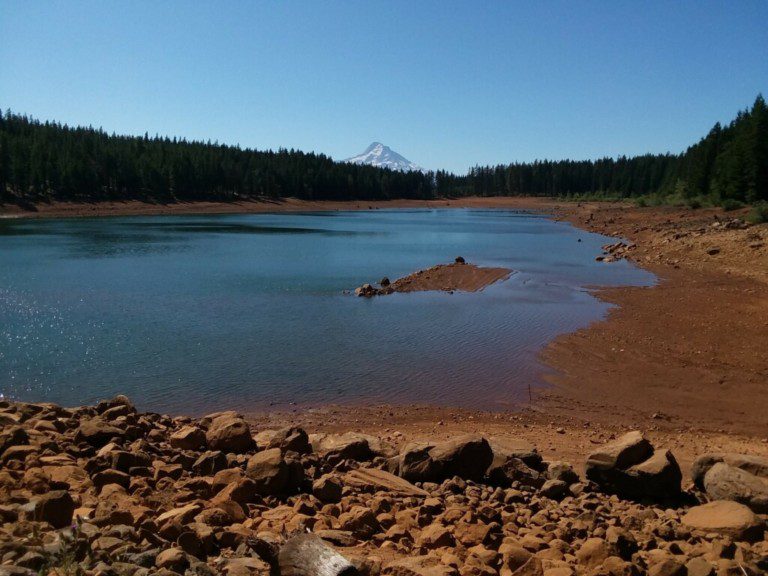

Better days: Snowpack across the Northwest is suffering in comparison with previous years. File photo: Idaho Farm Bureau Federation

By Kendra Chamberlain. February 6, 2024. Washington’s Statewide Drought Lead, Caroline Mellor, is predicting a tough spring for the state’s water rights holders.

The Washington Department of Ecology declared a drought emergency in 12 watersheds and across 12 counties last summer. There’s no indication the state’s water supplies will recover this year.

“Now is the time for water users to start making plans for a dry spring,” Mellor said during a water supply committee meeting last month. “Start thinking about your seasonal water rights transfers because there’s no reason to believe drought conditions will end soon.”

The Pacific Northwest has seen less snowpack this winter than normal, which will likely put irrigators in a tight spot during the summer months.

The Pacific jet stream is experiencing an El Niño weather pattern, which typically results in warmer and drier winter months for the region.

But research indicates climate change has been eroding snowpack levels across the northern hemisphere for the last 40 years as temperatures warm.

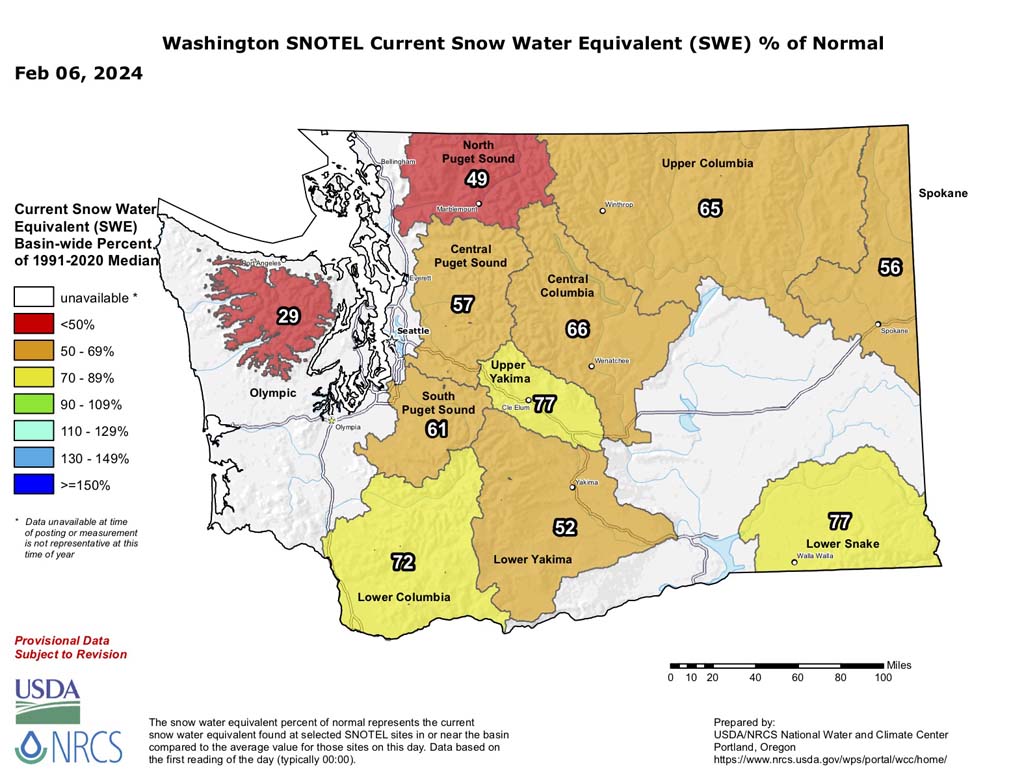

Map: USDA/NRCS

The water year so far, which began Oct. 1, has been warm and dry, leaving much of the region with below average snowpack.

Washington in particular has seen little snow accumulation so far this winter.

“They’re faring far worse in terms of snowpack, specifically the Olympic Peninsula, areas around Baker and the North Cascades National Park, and even down into the central Cascades in Washington,” Matt Warbritton, supervisory hydrologist at the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service, told Columbia Insight.

The lack of snowpack can be attributed to an unusually warm December—it was the third warmest December in Washington’s records, dating to 1895.

Temperature anomalies for the month of December ranged from 4 to 8 degrees higher than normal, representing huge shifts in temperature.

Snowpack was at record lows for the state at the start of January, and though the recent spate of winter storms did deliver significant accumulations of snow, it wasn’t enough to offset the deficit.

Idaho, Oregon also lagging

Snowpack across northwestern Idaho is also below normal, and the panhandle is currently at record or near-record lows.

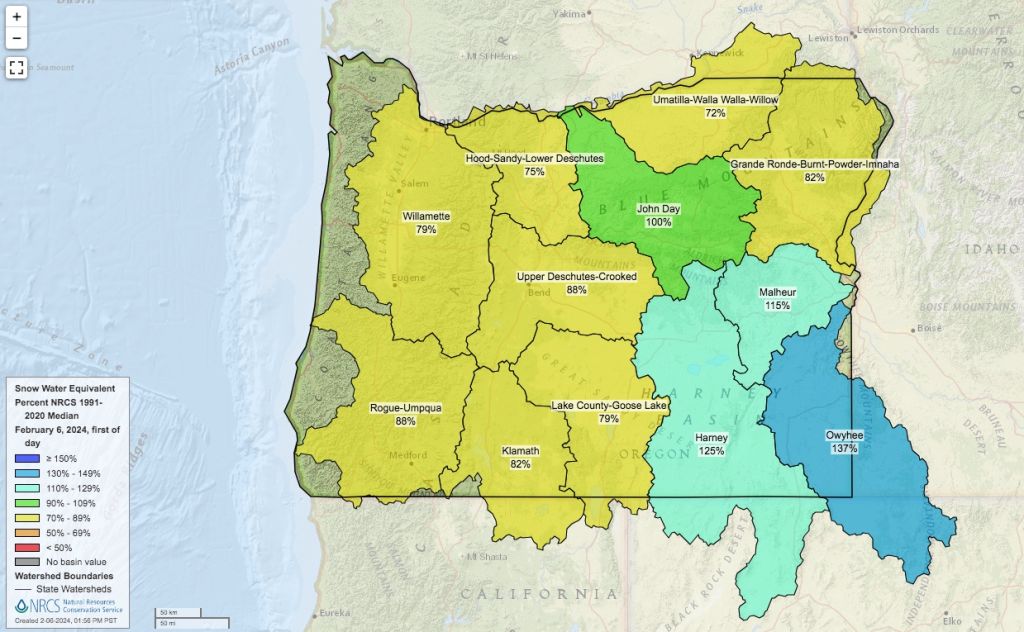

Oregon’s southern and western regions are also below normal, though much of the east side of the state has seen above average snow accumulation.

Oregon snow water equivalent map as of Feb. 6, 2024: NRCS

“In areas where there’s low snowpack, especially well below normal snowpack, this is going to have quite a bit of impact on summer water supplies,” said Warbritton. “Less water being stored as snowpack in the mountains means less snowmelt that’s going to be available to go into streams, and flow into reservoirs and fill those reservoirs.”

El Niño years often mean warmer temperatures and less precipitation in the spring months, which Warbritton said may potentially drive drought conditions and even increased wildfire risk later this year.

Snowpack declines likely to accelerate

Snowpack declines may be reaching a new tipping point, according to a study published last month in Nature.

The study found seasonal snowpacks across the northern hemisphere, including within the Columbia River Basin, have declined significantly over the past 40 years due to climate change.

The study determined the Columbia River Basin has seen a 4.8% decline in snowpack per decade since the 1980s, and predicts the Basin will see a 33% decline in snow water equivalent by the end of the century.

Study authors Alexander Gottlieb and Justin Mankin predict snow-dependent watersheds like the Columbia River Basin will see accelerated water supply losses over the next decades.

“We were most concerned with how warming is affecting the amount of water stored in snow,” Gottlieb said in a statement. “The loss of that reservoir is the most immediate and potent risk that climate change poses to society in terms of diminishing snowfall and accumulation.”