Sediment at river bottom is exposed for the first time in more than half a century

Green day: As this paddleboarder just upstream of the Bill Healy Bridge in Bend discovered, the Deschutes River looked a little different than usual on Wednesday. Photo by Ryan Brennecke/The Bulletin

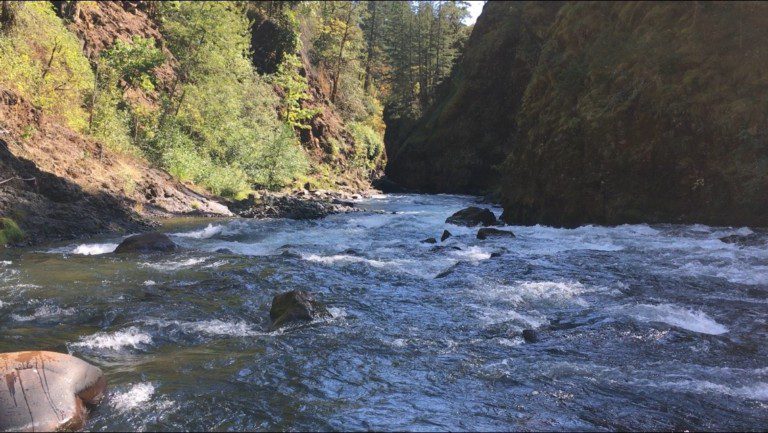

By Michael Kohn, The Bulletin. September 18, 2020. Hikers, anglers, kayakers and others who use the Deschutes River were greeted with an unusual sight on Wednesday, as water from the river turned a brown-green color.

The change in color comes days after Wickiup Reservoir ran dry—all that’s left is the Deschutes River running through the bottom of the reservoir. Sediment on the bed of the reservoir is being exposed for the first time in 70 years.

The discoloration is due to water being churned up by the river as it passes through the bed of the reservoir, said Kyle Gorman, region manager for the Oregon Water Resources Department.

“The flow through the channel in the reservoir is creating turbidity,” Gorman wrote in an email.

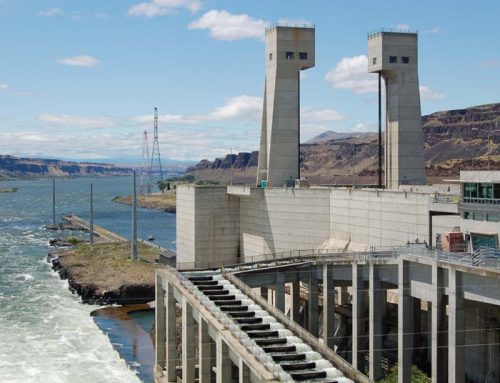

The Deschutes River begins its journey out of the Cascades at Little Lava Lake, flows south to Crane Prairie Reservoir, continues to nearby Wickiup Reservoir and then continues northward to Bend, eventually connecting with the Columbia River. River flow has been impacted in recent years by a number of factors, including reduced snowpack and prolonged drought, as well as requirements by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service to increase flows in winter to support Oregon spotted frog habitat.

The impact of the sediment on fish is not yet known. Chronic, high levels of turbidity can result in respiratory problems for fish by clogging their gill rakers, said Brett Hodgson, a fish biologist with the Deschutes District of the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. But turbidity is unlikely to have an impact if the water is murky for a week or less. A longer period could have “significant impacts” on fish.

“The fine sediments could get embedded in the gravels, impeding fishes’ ability to successfully spawn,” said Hodgson.

Macroinvertebrates such as caddisflies, mayflies, and stoneflies—insects that fish like to eat—could also be impacted by the sediment, said Hodgson.

There’s also concern about what will happen later this month when the flow of the Deschutes River is reduced to 100 cubic feet per second as part of the annual winter drawdown.

“Whatever sediment is deposited now will stay in the system and not be transported downstream,” said Hodgson.

Jeremy Giffin, watermaster for the Deschutes Basin, said he expects the water to clear up once the initial silt layer at the bottom of the old channel in Wickiup is washed away.

As of Wednesday the flow out of the river had dropped to 562 cubic feet per second, about half the rate that the river was flowing last weekend.

Columbia Insight is publishing this story as part of the AP StoryShare program, which allows newsrooms and publishing partners to republish each other’s stories and photos.

What does it look like downstream?

Are there studies/tests being done?