In the desolate northeast corner of Wyoming, home to Devil’s Tower National Monument, the Milky Way puts on a stunning display at dawn. Photo by David Kingham.

By Will Smith. April 4, 2019. A dark sky enriches the medley of sights and experiences that nightfall brings to our planet. By simply craning our necks, casual observers can witness the beauty of constellations and feel the intensity of meteor showers and eclipses. Introduce a telescope and we can marvel at the rings of Saturn, identify newly forming galaxies and see stars exploding from unthinkable distances.

All of this is hidden from view in cities, where ambient light pollutes the night sky and leaves only a few stars visible, even on moonless nights. But take an urbanite out of their well-lit city and into the darkness, and they can see the smear of millions of stars comprising our Milky Way Galaxy with their naked eyes.

Finding these dark corners in an ever-growing modern world, however, becomes more difficult each year.

The Importance of Darkness

Light pollution is getting worse, and it affects more than just the mere aesthetics of a stunning panoply of twinkling stars. A dark night sky plays a significant role in the feeding habits of aquatic species, the migratory patterns of birds, and even human health.

Artificial light disturbs delicate food webs in a number of unforeseeable ways. Too much of it delays croaking, an essential frog mating call, reducing populations. Birds wander off course, drawn in by the excessive light leaking out of scattered towns and cities. And as insects are attracted to the glow of a glaring bulb, predators take advantage of the easy prey.

Humans suffer too. Overexposure to ambient light disturbs our circadian rhythms and sleep cycles, having direct negative health impacts. The American Medical Association Council on Science and Public Health has stated that the “glare from nighttime lighting can create hazards ranging from discomfort to frank disability.”

Sleepless in Seattle: a view from Beacon Hill. Photo by Wonderlane.

And aside from its effects on wildlife and our own broken sleep patterns, excessive lighting directed into the atmosphere wastes energy, driving up costs for businesses, homeowners and all taxpayers. Proper lighting, which is shielded and directed downward (where we are actually using it) reduces energy use, and it just might improve your relationship with your neighbor.

But what about my safety?! Obviously a well-lit street will deter criminals, right?

Not exactly. While those bright street lamps might feel reassuring, multiple studies have shown that an increase in lighting does not necessarily correlate with a decrease in crime. In some cases when lights are too bright, our eyes adjust so much that we can’t see who or what may be outside that ring of light until it’s too late. One study in Chicago actually identified an increase in crime in more well-lit alleys – perhaps because the criminals could also see their victims and their property better in the glare.

With all these clear benefits associated with reducing the impacts of light pollution, interest in protecting dark night skies has risen over the last few decades.

Defenders of Darkness

The International Dark Sky Association (IDA) is the leading organization combating light pollution worldwide. The IDA has been working to protect night skies for present and future generations since 1988, and every year they identify places that are doing an exceptional job promoting stewardship of the night sky.

In 2018 the list topped 100 different Places in six categories: Parks (publicly or privately owned), Communities (cities and towns), Reserves (core areas with peripheral development), Sanctuaries (the most remote places), Urban Night Sky Places (areas surrounded by large urban environs designed to offer unique access to the Dark Sky in otherwise brighter cities), and Dark Sky Friendly Developments of Distinction (subdivisions, master planned communities, etc. that exemplify Dark Sky protections).

In 2001, Flagstaff, Ariz. became the world’s first International Dark Sky Community. Since then, 14 more have been added in the United States.

[robo-gallery id=”10878″]

The only internationally recognized Dark Sky Places currently in the Northwest are in Central Idaho: the community of Ketchum, and a Dark Sky Reserve covering 906,000 acres between Sun Valley and Stanley. This is the only such Reserve in America and, as the author can attest, it is home to truly spectacular night skies.

For a few years, however, there was another bastion of dark skies in the Northwest that was recognized by the IDA as a Dark Sky Place: the Goldendale Observatory State Park in Washington. While there are now over 100 International Dark Sky Places certified around the world, in 2010 the Goldendale Observatory State Park was the sixth to be recognized, and the second state park in the US to receive this prestigious designation.

Thousand of tourists and amateur astronomers are drawn to the Observatory each year, primarily because of its remote location. Willamette Valley observatories are situated too close to major cities to offer the same level of night sky clarity that can be found east of the Cascades. And since the next closest Dark Sky Parks are in Utah and Southern California, the Observatory is ideally situated to provide a uniquely dark experience for those living and traveling in the Pacific Northwest.

But the IDA revoked the Observatory’s status in 2017 — the first and only time the organization has decertified one of their Dark Sky Places. This left the Park and the City scrambling to readjust their priorities in order to obtain it once more.

The Goldendale Observatory. Photo courtesy of Friends of the Goldendale Observatory.

Two years prior, in 2015, Goldendale amateur astronomer Bob Yoesle was one of a handful of advocates worldwide who was presented with a Dark Sky Defender Award from the IDA for his role in helping the Observatory maintain its status. A few years later he was instrumental in identifying the failure of both the park and the community to preserve this resource.

“The biggest problem is ignorance,” Yoesle explains. “People aren’t aware of it, you know. We have a city and a county that wants to have the Observatory for commercial exploitation, but doesn’t want to protect it.”

Yoesle advocates tirelessly for night sky protection. He manages the non-profit known as Dark Sky Defenders and volunteers his time to give educational presentations up and down the West Coast, promoting the reduction of light pollution.

“My view of it is: if you really care about something, you do something about it. And if you just say you care about it, but you really don’t, then you have the situation we have here,” Yoesle says.

He blames City and Park leadership for not sufficiently protecting the night sky in accordance with IDA requirements, and says that the lack of a sufficient monitoring program clinched the loss of Dark Sky Park status for the Goldendale Observatory.

According to Ryan Karlson, Washington State Parks Interpretive Program Manager, the Park “had some reporting requirements that weren’t satisfied.”

“Since then,” he says, “we have made structural changes to how the agency manages the program, clarifying expectations, and we now have a clear understanding of what [the requirements] are now.”

The Observatory’s main focus at the moment is on their current expansion project, which has been underway since 2014. With the exception of the dome itself, State Parks is reconstructing the entire building. They are working with the IDA to establish a dark sky compliant lighting plan for the facility, with the goal of modeling what modern dark sky stewardship looks like and inspiring visitors to think about their own home’s light pollution impacts. On-site programming will provide opportunities for visitors to value the dark sky experience and learn more about how this natural resource is vulnerable to light pollution.

“We value our relationship with the IDA,” Karlson emphasizes.

“But even without the status, we are moving forward with Dark Sky stewardship investments.”

Once they complete the expansion (currently targeted for the Fall of 2019), they intend to complete their application for Dark Sky Park status and to work with the local community to ensure that is accomplished.

Reclaiming Darkness

Meanwhile, in Goldendale, new high tech lighting has been installed with a system that gives the City control from a central hub. This system enables them to easily dial the intensity of the lighting down when it is needed less, such as later in the night, or when the Observatory is hosting a special program and requests temporarily darker skies.

The Big Dipper shines prominently over Mt. Adams as light pollution from Seattle, Tacoma and Olympia bleeds into the night sky. Photo by Irene Fields.

These improvements are overdue since, as Yoesle points out, both the City of Goldendale and Klickitat County bear some of the responsibility for the Observatory losing its status as a Dark Sky Place. Their outdated lighting ordinances, and lack of enforcement or implementation of them, contributed to the excessive amount of light pollution around the Observatory, he says.

“These ordinances have been in place for decades,” he says, “and they can’t even fix the lights on their own publicly owned city and county buildings.”

“They are some of the worst offenders,” Yoesle continues, “and they’re not setting any kind of example for the public.”

“Although the ability to dim LED street lighting sounds good,” he says, “it does not represent the magic bullet solution that [Observatory Administrator] Carpenter and the City/Chamber want everyone to believe. A significant part of the problem from Goldendale and Klickitat County comes from poorly shielded non-compliant lighting on commercial, municipal, and residential property, which the ordinances are meant to address, and which are both inadequate to begin with and unenforced.”

But Goldendale, as it turns out, is not the only Gorge community with active citizens concerned with protecting their night sky.

Mosier, a small town on the other side of the Columbia, is also vying to be the first Dark Sky Community in the Gorge. After a recent presentation to the City Council by Mike McKeag, Outreach Coordinator for the Rose City Astronomers Club, the City decided to form a committee to explore applying to the IDA for that status. The committee, which includes Mr. McKeag, two city councilors and other local citizens, had its first meeting in January.

Photo by Mike McKeag

McKeag estimates that it will take at least a couple of years to go through that process, but that the ongoing commitment is what matters to the IDA. He explains that “the application process includes completing some actual projects, including adopting an acceptable lighting ordinance, and at least one physical lighting project.” After achieving any street light modifications, and planning for new development to use best practices in avoiding light pollution, a monitoring program would be necessary, and would include regular status reports to the IDA.

Then there is the Columbia River Gorge Commission, which works to protect scenic, natural, cultural and recreational resources, while also encouraging sustainable economic growth in portions of six counties in the Gorge. Promoting Dark Sky Places aligns seamlessly with these goals, and the Gorge Commission fully supports voluntary efforts to encourage the protection of the night sky.

Jessica Olson works for the Gorge Commission, and she notes that their Management Plan already has policies in place that require hooding and shielding of lights in areas visible from what they identify as “Key Viewing Areas,” such as I-84, Highway 14 and several vistas.

And since the Commission is in the middle of updating its Management Plan, known as Gorge 2020, Olson says this is a perfect opportunity for citizens to speak up in favor of strengthening and expanding these policies.

She also says that the Commission is currently working to install measurement systems that would generate baseline data for current levels of light pollution throughout the Gorge. With these baseline measurements in place, any future changes in the amount of light pollution could then be tracked.

This is an important step in determining whether or not the Observatory, along with the communities of Goldendale and Mosier, can reach their full, inky potential with the support of private citizens and government agencies. If so, the Gorge may soon be home to two Dark Sky Places, ensuring brilliant midnight spectacles and benefitting all species that depend on darkness.

Lost in Light from Sriram Murali on Vimeo.

Additional Resources:

An interactive light pollution map of the United States

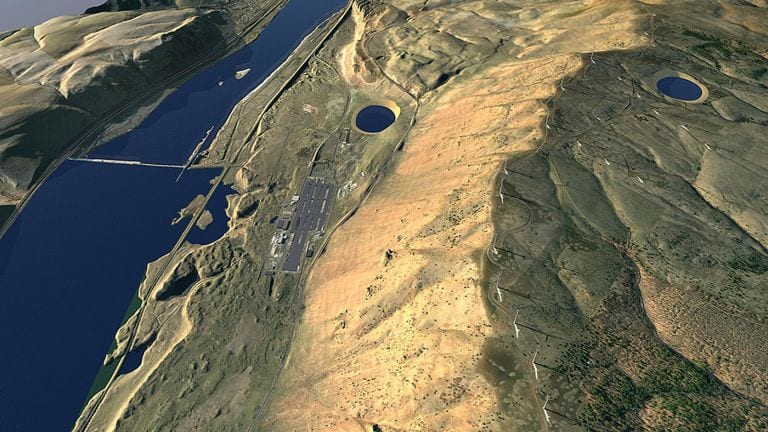

Satellite imagery from NASA’s Earth Observatory

To get involved, contact your local city or county government and express interest in preserving dark skies in your community. You can provide input to the Gorge Commission by visiting their Gorge 2020 website.

You can also consider attending a Star Party, which are annual, family-friendly gatherings of amateur astronomers and night sky enthusiasts. Upcoming Star Parties include:

Table Mountain Star Party: July 30-Aug. 3, 2019 in Oroville, Washington.

Oregon Star Party: July 30-Aug. 4, 2019 in Ochoco National Forest, Oregon.

I met Bob Yoesle in April of 2016, when he brought his Solar Telescope to the Columbia Gorge Discovery Center in The Dalles. It was nice because the public could look at amazing views of the sun, solar flares, and sunspots, for free. He also led community discussions about light pollution at the Discovery Center around that time. I’m glad communities are least trying to talk about the issue. But if your town doesn’t have a professional observatory, like Goldendale (which, by the way, is closed due to a major telescope upgrade project) it’s probably hard to generate interest in spending public money, and the backyard hobbyists need to work issues on a local level (like asking neighbors to turn lights off if possible). It’s interesting and concerning that some species, including ourselves, can be affected by light pollution. I also find it ironic that the Gorge Commission calls I-84 a Key Viewing Area. Myself and countless others have complained that you can’t see five feet in front of you if you’re driving from the Gorge to Portland (or vice versa) at night in the rain. Partly due to the glare of oncoming headlights and the high-beams from behind in your driver’s side mirror. That’s the light pollution I’d like to see eliminated.