Citizen scientists are also major contributors to a project that utilizes the freshwater crustaceans in a novel way

Rare quality: The signal crayfish is native to the Pacific Northwest. Most varieties of crayfish found in the region are not. Photo: Astacoides/Wikimedia Commons

By Kendra Chamberlain. August 15, 2024. Environmental workers come in all varieties but, fairly or not, they’re often tagged with a set of stereotypes: determined, resourceful, prickly, crunchy.

No matter their widespread validity, these qualities certainly apply to the latest group of enviro warriors—crayfish.

For the past four years, a team of researchers from the University of Idaho has been capturing crayfish from water bodies across the Columbia River Basin to examine levels of mercury found in the crustaceans’ tails.

The Crayfish Mercury Project is a pilot for using crayfish as a “biosensor” to track pollutants in watersheds across the Columbia River Basin.

While the research is focused on mercury, crayfish could also be used to track other persistent organic pollutants (POPs), such as PCBs or DDT that are present and moving through the Basin.

The project also offers a proof of concept for leveraging community-based science to conduct research.

The team has tapped into networks of community members to help generate data points. So far, more than 500 volunteers in Montana, Idaho, Washington and Oregon have helped the team collect some 1,200 crayfish to sample.

Crayfish as biosensors

Measuring levels of pollutants in water bodies is harder than you might think.

“If you were to go out to most of the areas within the Columbia River Basin and just pull up a liter bottle full of water, the chance of measuring detectable mercury or PCBs or DDT metabolites is actually fairly low. Not zero but fairly low,” says Dr. Alan Kolok, lead researcher at the Crayfish Mercury Project and retired professor at University of Idaho.

That’s where the crayfish come in.

Crayfish accumulate non-metabolizable compounds such as mercury, DDT, PCB and PBDE (polybrominated diphenyl ethers, a class of manmade, fire-retardant chemicals) at a linear rate, which means they’re incredibly useful for monitoring those chemicals, according to Kolok.

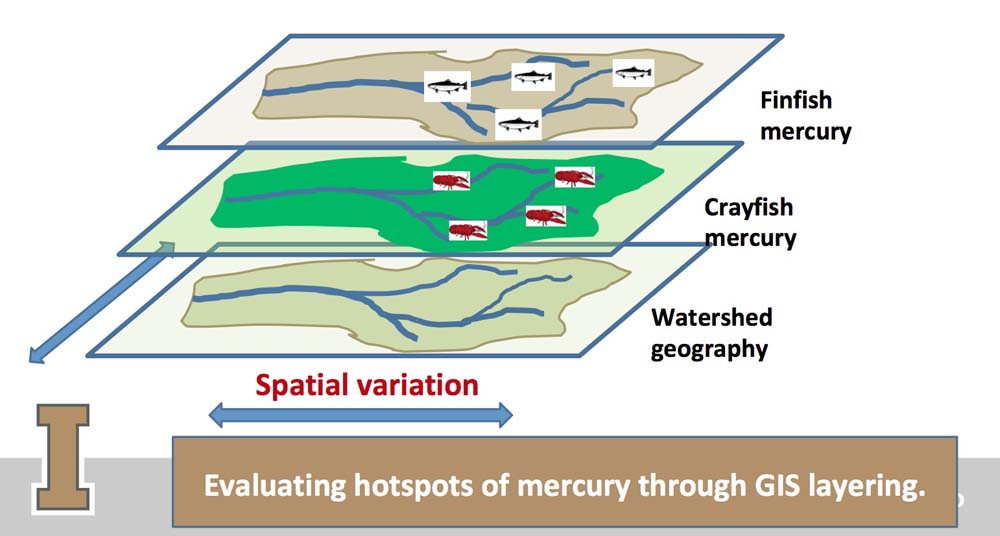

Data gathered by the Crayfish Mercury Project could be layered with other mercury monitoring data to create a geospatial map of mercury in the Columbia River Basin. Graphic: Alan Kolok/University of Idaho

So far, the team has sampled crayfish from Clark River in Montana, the Boise River and its tributaries in Idaho, the Spokane River and its tributaries in Washington and the John Day River in Oregon.

“Full disclosure. We have not seen anywhere where the levels are so high that they are actually high enough to manifest public health concerns,” says Kolok.

It’s worth noting the state of Oregon recommends limiting crayfish consumption to two meals per month in the Lower Willamette due to higher levels of PCBs.

One of the goals of the project is to collect enough data points to establish a Basin-wide map of mercury concentrations, standardized across the multiple species of crayfish present in the region.

This data, coupled with watershed geography and datasets of mercury monitoring in other aquatic species, can be leveraged as a sort of geospatial evaluation of mercury in the Basin.

Such a map would help address data gaps around mercury levels in the region.

It would also help researchers understand how mercury moves through the environment.

Mercury in the Basin

Mercury is a widely distributed pollutant across the entire Columbia River Basin.

It travels primarily through the air—the EPA calls this “atmospheric deposition”—and was released for decades across the West through fossil fuel combustion, mining and other industrial processes.

“It’s incredibly hard to pinpoint the sources of mercury,” says Tate Libunao, a graduate student working on the project. “However, there are some identified point sources, such as older, reclaimed mines with exposed ore. There are a number of Superfund sites, both within Idaho as well as in northeastern Washington, that have had historical inputs of mercury.”

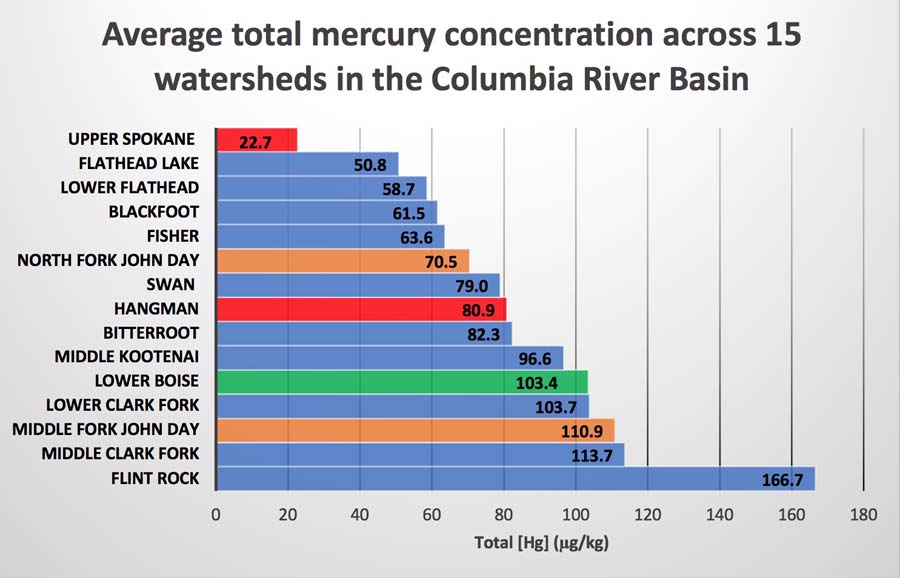

Average total mercury concentration (µg/kg, wet weight) found in the adductor muscles of 350 crayfish across 15 watersheds. Green=Idaho, Blue=Montana, Red=Washington, Orange=Oregon. Graph: Crayfish Mercury Project

Some of the mercury present in the Basin is from geogenic sources—meaning the mercury is released through naturally occurring sources such as rock formations and volcanic eruptions.

In the last decade, wildfire has become a large source of re-released mercury in the West, according to a report from the U.S. Geological Survey.

“Mercury is kind of an oddball in the elemental world, which makes it really interesting, and also makes it really, really toxic, both to the environment and to humans,” says Kolok.

For one thing, mercury is fat soluble, rather than water soluble, like most other metals.

Mercury partitions into the fats of the soil or sediment in a body of water, or in the tissues of organisms that live in water.

This is important because it means mercury—unlike other metals—is biomagnified as it moves through the food chain.

Today, there are fish consumption advisories for mercury in every state within the Columbia River Basin. Resident fish such as bass and walleye are of particular concern because they eat other resident fish and so have higher levels of mercury in their fatty tissue.

Citizen science gaining momentum

Data gaps in mercury levels are in part due to the sheer magnitude of sampling required.

Measuring mercury in every waterway within the Columbia River Basin would be a massive undertaking. There are too many streams, creeks and tributaries for a small team to tackle.

Watching the detectors: Volunteers from Spokane Riverkeeper collect crayfish on the Upper Spokane River. Photo: Crayfish Mercury Project

Kolok and Libunao have found a solution: citizen science.

Citizen- or community-based science relies on volunteers across a wide geographic area to conduct research on behalf of a research team.

Kolok points to the Christmas Bird Count, a 120-year-old tradition of bird-watching across the Western Hemisphere. Bird counts are gathered from individuals in 20 countries. Some findings have proven useful in tracking climate change impacts.

The Crayfish Mercury Project has partnered with organizations including Montana Fish and Game, Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission, Boise River Enhancement Network, Salish School of Spokane and Spokane Riverkeeper. These organizations have supplied hundreds of volunteers to collect crayfish for the project.

Kolok believes citizen science is “a burgeoning field in environmental monitoring.”

He’s authored two papers exploring how citizen scientists might help expand different types of monitoring of environmental contamination.

It’s also empowering to community members interested in learning more about the health of fish and waterways.

“We’ve actually inquired back to our participants, what do you value the most about this project?” says Libunao. “Time and time again, they talk about how they thoroughly enjoy a scientific authority to come out to educate the non-science community and bring awareness of whether the crayfish are safe to eat and what’s the health status of our waters in which we invest so much time and energy into safeguarding?

“In my experience, it’s been an incredibly rewarding one, because I get to effectively serve the community that I’m a part of. It’s been so gratifying in that context.”

Interesting article – thanks. I’m glad to see you switch to “Community Science” (or participatory science) since not all folks who do this kind of work are actually citizens. Also I appreciate the Elvis Costello reference

I knew someone would get that reference! Thanks. —Editor

I grew up in Iowa fishing and catching crawdads. Used the crawdads for catching catfish.

This article is well written. The use of students to help gather the crawdads is great. Hopefully these studies will help get mercury cleaned up and provide information to people like Native Americans who eat fish from these rivers.

A crunchy former fisher-person.