A critical stopover for migratory birds in the Pacific Flyway is in trouble. Researchers are trying to get a handle on the problem

Flight risk: Wilson’s phalarope are just one species of birds use the Pacific Flyway. Many of its critical stopovers are drying up. Photo: Tom-Koerner/USFWS

By K.C. Mehaffey. March 6, 2025. If you’re in the right place at the right time, you might catch one of nature’s truly great performances.

The right time is late summer or early fall, when thousands of Wilson’s phalaropes make a stop in Oregon on their 4,000-mile migration to winter in South America.

One of the right places is Oregon’s Lake Abert in the SONEC region, an acronym for the vast mosaic of lakes and wetlands stretching from southern Oregon to northeastern California.

Phalaropes stop at Lake Abert and other saline lakes in the western United States to double their body weight so they can finish the journey. Gorging on insects, brine flies and brine shrimp, phalaropes use this time to molt their feathers and increase their fat reserves.

When they forage, phalaropes spin in circles along the lakeshore, creating a whirlpool that brings prey toward the surface, where they gobble them up.

“They look like little, aquatic ballerinas,” Teresa Wicks tells Columbia Insight. “Sometimes you see them on bodies of water where hundreds are spinning at once in these tight little circles.”

Wicks—the eastern Oregon field coordinator for the Bird Alliance of Oregon—says it’s a sight no one forgets.

Phalaropes aren’t like other birds.

The females are larger and showier than the males, with a golden-brown neck, a gray cap and back, and a black stripe from their beak through the eye and down to their shoulders. Those colors are accented by beautifully bright, white feathers on their cheeks, chest and sides.

The males are similarly marked, only duller. They take on the chore of caring for the chicks.

Wicks says if you approach too quickly, “the males will flush up and fly around you, and they make this very funny sound, almost like a really, really deep kazoo.”

Like so many shorebirds in North America, however, Wilson’s phalaropes have experienced sharp declines in population over the last few decades.

“Wilson’s phalarope populations have fallen approximately 70% since the 1980s because of extensive habitat destruction, water diversions and persistent drought,” according to the Centers for Biological Diversity, which filed a petition in March 2024 to list them as a sensitive species under the Endangered Species Act.

Where have all the shorebirds gone?

Wilson’s phalarope is a kind of shorebird, an order of birds sometimes called waders that can be found walking or swimming along shorelines looking for food.

Plovers, avocets, killdeer and sandpipers are other members of the order Charadriiformes.

In 2019, a study that looked at net population changes of 529 species of birds that breed in the United States and Canada revealed a loss of nearly 3 billion birds in the previous 50 years—roughly one in four birds.

A few groups—like geese, swans and ducks—grew in population.

But there were losses in almost every other category, including many common birds.

Shorebirds and grassland birds suffered the highest declines—with populations dropping by about one-third since 1970.

Pacific Flyway map: Columbia Land Trust

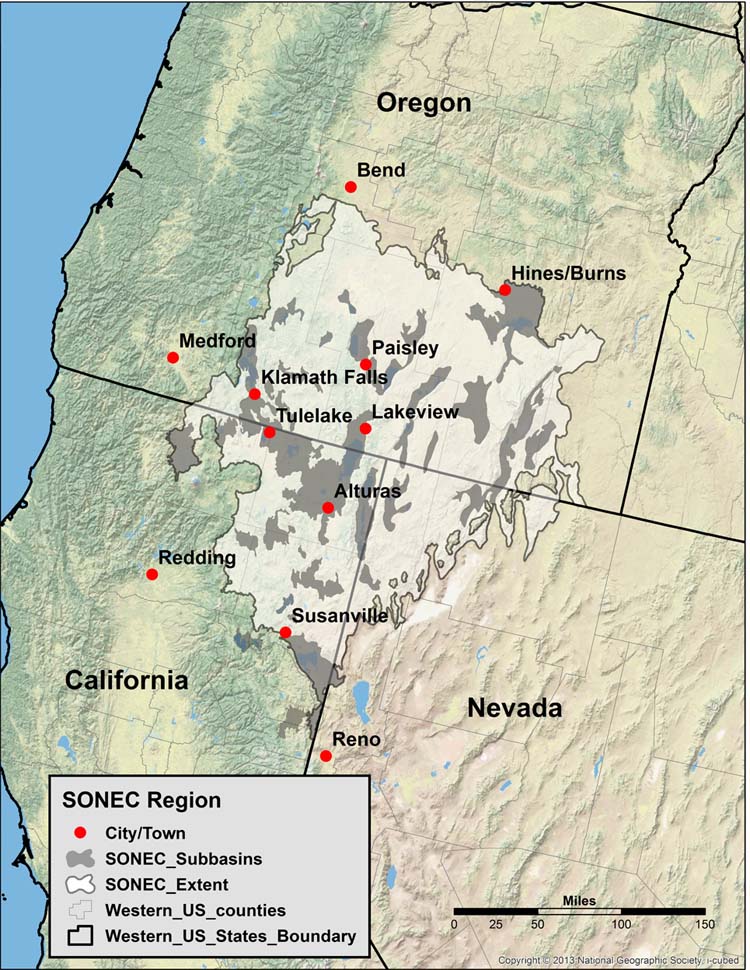

Various kinds of shorebirds are among the 80 bird species that depend on the SONEC region, comprised of eight counties in Oregon, California and the northwestern tip of Nevada.

Emily VanWyk, acting conservation strategy coordinator for the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife, says that about 70% of migratory wetland-dependent birds in the Pacific Flyway—some 6 million birds—will use this habitat each year.

“Oregon plays a key role in the conservation of all of those species, even those that might only spend a week or a couple of days in our state,” she says.

VanWyk and Sarah Reif, ODFW’s habitat division administrator, gave a presentation to the Oregon Fish and Wildlife Commission in June 2024 as part of a series of reports on adapting to climate and ocean change. It focused on the importance of the SONEC region to migratory birds.

“It’s important to raise these concerns with the commission and the public in recognition of the biodiversity crisis,” VanWyk tells Columbia Insight. “ODFW is invested in the conservation of all these migratory bird species. We want to do more to protect them and their habitat.”

The loss of 3 billion birds across North America wasn’t caused by one thing.

The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service has a long list of human-caused threats to birds, from collisions with buildings, communication towers, electrical lines, vehicles and wind turbines to poison and predation by cats.

But, the agency notes, “Habitat loss is thought to pose by far the greatest threat to birds, both directly and indirectly, however, its overall impact on bird populations is very difficult to directly assess.”

Super SONEC

Dominated by sagebrush and generally arid, the SONEC region provides a variety of wetland types that serve as highly productive breeding habitats and critical stopover sites for birds traveling from the Arctic to Central and South America.

But it contains a series of closed-basin or terminal lakes, wetlands and alkali flats that recharge each year with snowmelt. The amount of water in these closed systems can fluctuate dramatically over the course of a year, and from year to year.

In recent years, the system has been under long-term drought, driven by climate change.

SONEC map: Intermountain West Joint Venture

Higher temperatures, less precipitation and the increased use of both ground and surface water by people have contributed to declines in water levels within the region.

The declines in water levels have been exacerbated by wildfires, which have caused increased runoff rates, decreased infiltration rates and impacts to water quality, according to VanWyk.

“As those effects combine, we see population declines, including new data documenting a decline of up to 10% per year between 2012 and 2022 for some species of shorebirds within the Pacific Flyway that come through terminal lakes in Oregon,” she says.

One of the problems is the loss of functional habitat. A semi-permanent wetland may become a seasonal wetland that becomes temporarily dry.

“As water evaporates and isn’t replenished, those habitats become unsuitable for the invertebrates that birds consume, and that can diminish the food that’s available,” she says. “It’s still wetland, but is it providing habitat for the species we’re concerned about?”

Botulism outbreaks at Tule Lake

The June 2024 presentation came a day after commissioners visited the upper Klamath Basin, learning about partnerships for managing water and plans to reintroduce salmon after the removal of four dams in 2024.

The upper basin includes Northern California’s Tule Lake National Wildlife Refuge, where some 60,000 birds died in 2020 from botulism. Just a few months after the commission’s visit, a second botulism outbreak killed an estimated 80,000 birds.

“When 60,000 or 80,000 or however many thousand salmon die, it’s front-page news, above the fold. We talk about it for 25 years like it happened last week,” said Commissioner Dr. Leslie King. “When that many birds die, there’s barely a blip.”

Dry not high: At high water, Summer Lake in Lake County, Ore., supports a variety of birds and other wildlife in its marshes. Photo: fishermansdaughter/Flickr

Dr. King noted that in Klamath Basin, the wildlife refuge is last in line for getting water.

“The Everglades of the West became a mud puddle, basically, meaning the wildlife area didn’t get any water,” she said. “And so, a lake was a mud puddle, the ducks came along, stirred up the botulism, and by the tens of thousands died.” (Mallards were one of the species most affected by the botulism outbreaks.)

“How do we advocate for these birds?” replied VanWyk. “How do we make an argument that’s effective, because, you’re right, this is a huge concern. We’re losing thousands of birds. It’s scary.”

In an interview with Columbia Insight, VanWyk said a botulism outbreak could be a concern for other wetlands in the SONEC region, because the bacteria Clostridium botulinum, a naturally occurring toxin, becomes concentrated under low- and warm-water conditions.

“We’re concerned about it because there’s less and less water available on the landscape,” said VanWyk.

Despite the dire situation for many bird species in North America, Wicks sees a ray of hope.

“There’s been a lot of work to create momentum around public-private partnerships. I would say in the last five years, that has really started to take off,” she says.

Collaborative solutions

One of those partnerships is a massive effort to survey shorebirds as they move through the interior portion of the Pacific Flyway each spring and fall.

The Intermountain West Shorebird Surveys began in fall 2022 and will conclude in 2026. Led by Audubon and Point Blue Conservation Science, the project is documenting the distribution and abundance of shorebirds in the interior West—information that was last collected between 1989 and 1995.

Blake Barbaree, senior ecologist with Point Blue, says the survey effort involves hundreds of volunteers and a network of more than 60 government agencies and nonprofit organizations.

He says it wouldn’t be possible without funding and technical support from the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and state fish and wildlife agencies in Oregon, California, Nevada, Utah, Idaho and Montana.

Full stop: When full, Lake Abert covers 65 square miles and is the sixth largest lake in Oregon. It’s five-feet deep on average and one of just three hypersaline lakes in the United States. Photo: Joan Holzer/BLM

In spring and fall, the groups survey more than 200 sites, ranging from large, critical migratory stopovers, like Great Salt Lake, to small reservoirs and wetlands.

“Essentially the interior region was identified as a large data gap. We don’t understand a lot about the distribution of shorebirds, or about the wetlands’ health and how that’s actually impacted bird populations,” says Barbaree.

Once complete, the current surveys can be compared to surveys from 30 years ago, which will provide a better understanding of the extent of and reasons for shorebird declines in the Pacific Flyway.

Barbaree says one of the goals of the survey is to understand how the drying up of wetlands is tied to shorebird populations.

There are numerous important stopover sites for shorebirds throughout the interior region. Barbaree says the SONEC region is one of them because it supports a large variety of wetland types.

The Klamath Basin, for example, is mostly freshwater, and is hugely important for waterfowl. Not far away, Lake Abert is much saltier, and attracts birds like phalaropes.

“It’s a lot shallower and has this saline component that is very productive in small invertebrates, so it’s really, really attractive to migratory shorebirds,” says Barbaree.

Other lakes in the SONEC region are somewhere between freshwater and saline wetlands, such as Summer Lake in Oregon.

“That diversity of wetland types makes the SONEC region unique and attractive,” says Barbaree.

Some migratory bird species appear to be flexible, and when they find a stopover location has dried up, they keep flying until they find a suitable spot to recharge.

“But we don’t know the cost of that,” says Barbaree. “If I’m showing up to the lower Klamath refuge and there’s no water there this year, I can keep flying 50 to 100 miles to find the next place. But if I’m in a flock of 100 birds, how many of them make it?

“There’s also the potential for cumulative effects. If I’m traveling from Mexico to Alaska and two spots didn’t give me food, am I going to have enough resources to make it all the way?”

Although survey data has been gathered for more than two years, Barbaree says it’s too soon to draw conclusions.

“Our hypothesis is there’s been a significant decline [in bird populations using the SONEC region] given what we know about the wetlands systems. Whether we can support that with the data is still to be determined, but everyone will be astounded if there’s not a certain level of decline for a portion of the species,” says Barbaree.

Water rights for birds?

Wicks says her hope is that all of the monitoring efforts will highlight the relationships between birds and fish and wetlands so that water can be secured to support wetlands every year.

“Our goal is to protect wetlands and restore wetlands in the SONEC so they are able to support healthy bird populations,” she says.

Tripping: Northern pintail are one species of an estimated one billion birds that use the Pacific Flyway. Photo: Bob Wick/BLM

Barbaree says that as an organization focused on gathering scientific research, Point Blue doesn’t have a position on whether advocacy groups should be trying to acquire water rights for birds and the wetlands they depend on.

“We’re trying to understand the ecosystem from the bird’s perspective, and how that’s changed over time,” he says.

Still, the information they gather can be used to identify species that may need support, or specific wetlands that are most important to them.

“If, say, Lake Abert is looking way worse than Summer Lake, it can help us identify how we target our conservation dollars,” he says.

But, Barbaree points out, water laws are complex and securing water rights for birds may not be a viable path.

He says he’d be surprised if codifying environmental use of water as a beneficial use will become a reality in most places.

Even so, he says, “I think in general there’s a better understanding that healthy, long-term water ecosystems are important to everyone. We have to give back. We can’t take it all.”