By Susan Hess. Aug. 14, 2017. John Buckley stood at East Fork Irrigation District’s headgate looking up the river. It’s one of his favorite places.

The East Fork of the Hood River runs through a dense forest at that spot, rumbling over the rocky bed, rocks swept down off Mt. Hood.

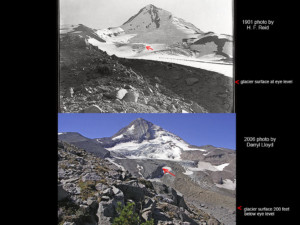

Mt. Hood’s shrinking glaciers by Darryl Lloyd.

Buckley, the district’s manager, comes to this critical spot often. It’s where East Fork diverts the amount of water it’s allowed. Since the 1890s, the district has held a legal right to take water from this river.

Each summer Mt. Hood’s glaciers’ slow melt provided farmers ample water. But scientists predict that the glaciers will lose 96 percent of their current size by 2100, and that East Fork may be dry in late summer, when crops need it most.

“To meet climate change,” Buckley said, “we plan to put in maybe two to three medium size reservoirs, and put in more piping to convey water rather than open canals. And pray a lot.”

The planned reservoirs will capture rain and seasonal snowmelt. What will the water right be then? How will it affect the water rights of those downstream? Whose rights come first: cities? agriculture? fish? wildlife? One always comes last.

The issue has led to heated fights and the upending of long held rights in the Klamath Basin, the Sacramento River, and the Colorado River. Those who cannot speak for themselves often get pushed to the back of the line or overlooked as OPB’s feature pointed out in Birds Take Backseat To Fish, Farms In the Klamath Basin.

The right to water. In the western United States (west of the Mississippi River) water law is: first in time, first in right. In the west, the first person to get a water right on a stream/river is the last to be shut off in times of low flow. First come, first served. In Oregon and Washington every molecule of water has a right attached to it. Still, more people are and will be looking for water.

In the next 20 years, Hood River County’s population is projected to increase by 25 percen—adding over 6,000 people, Wasco County by 4,400.

With no access to new water rights there are increasing attempts to privatize public water. People who live in the Columbia River Gorge saw this first hand with Nestlé‘s proposal to obtain the publicly owned rights held by Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife. Their application is still to be processed. Whatever is ahead, agriculture is on the front line.

In the Gorge, agriculture holds the largest amount of water rights.

2014 was the hottest year on record for Planet Earth. 2015 hotter. 2016 hotter yet. The planet has now had three consecutive years of record-breaking heat. And drought is temperature driven.

“We’re seeing more volatility in temperature year round and higher spring temperatures,” said Mike Omeg who grows cherries on 330 acres south of The Dalles. “We come out of spring same as in the past. But it warms up quickly. 2015 was the earliest year ever, and 2016 beat that.

“So we irrigate with more intensity earlier. Crops grow faster because of higher temperatures. We may begin watering three weeks earlier and then at the end of the irrigation season, water three extra weeks. So total amount of water we use increases.”

Four Hood River County irrigation districts hold water rights: East Fork, Middle Fork, Farmers, and Dee. In Wasco County, the main district is The Dalles Irrigation District. The two counties use different water sources, and because of that, their effects on the environment differ.

Hood River’s irrigation water comes from Mt. Hood. The Dalles Irrigation District pumps water out of the Columbia River.

EFID head gate. The district keeps 15 cubic feet per second flowing past this diversion to ensure water for fish.

Hood River irrigation districts divert water coming off the mountain high up in the valley. It’s a money saver because water can be gravity fed to patrons.

The problem with taking water out high in the watershed is that it decreases instream flows and that impacts fish. “If you’re taking it out higher up in the system, it’s not available for aquatic organisms for a good portion of the length of the stream,” said Cindy Thieman, Hood River Watershed Coordinator. “Salmon in particular are going to be occupying those areas downstream.”

“It’s living space for fish,” Thieman said. Less water equals less fish habitat for food and spawning and increased disease. Stream and river temperatures rise, especially in late summer. The Hood River (main stem) is listed by Oregon DEQ for exceeding temperature standards. Salmon need cold water. Every degree rise decreases oxygen for them to breath.

The Dalles Irrigation District (TDID) The district pumps out of the Columbia to reservoirs 1,300 feet uphill. Pumps push enormous volumes of water up an elevation equivalent to a 120 story building. Water is heavy. Power is expensive. Through a long term agreement, the Bonneville Power Administration sells power to them at cost.

The Dalles Irrigation District water intake on the Columbia

“Without that rate, the assessment would be astronomical,” said TDID Manager, Danny Saldivar. “For smaller farmers it would affect the way they do their farming.”

The issue for fish is that irrigators are pumping water out of the Columbia River along its entire length. This is a basin that stretches to the Tetons and far into Canada. Cumulatively they leave a river often too hot for sturgeon, lamprey, and salmon–they, too, have water rights.

The State of Oregon has instream water rights to protect fish. But those rights are junior rights, for some puzzling reason not acquired until 1987, versus FID’s 1874 right. All Hood River irrigation districts hold rights senior to instream, said Les Perkins, Farmers Irrigation District Director. So in a drought, they have a legal right to dewater the rivers. “But,” Perkins said, “it would be folly to do that.”

The Tribes’ rights. The Confederated Tribes of the Warm Springs treaty gives them the right to fish throughout their ceded lands, which takes in all of Hood River and Wasco Counties and beyond. Even though the Tribes want to keep water in the rivers for fish and the districts want to take it out for crops, there is a mutual respect between them. East Fork has agreed to keep 15 cubic feet per second always flowing in the East Fork of the Hood River. Still, the tribe has made it clear that to protect fish they would sue to prevent dewatering.

Blaine Eineichner photo: Chinook Salmon

The Cities. Millions of people depend on Mt. Hood for water. On the mountain’s west slope lies Portland’s Bull Run Reservoir, to the north the City of Hood River owns three springs, and to the east side signs mark the boundaries of The Dalles watershed. You would think that fish, which were here long before humans arrived, would have a prior claim on water, but as with the irrigators, the city’s rights are senior.

Meeting competing demands. One way to get more water to meet demand is to eliminate waste. Farmers, as a group, are way ahead in using water more efficiently. One method is using pipes instead of open canals: reducing water loss due to seepage and evaporation by 30 to 40 percent. Perkins said, “We are using half as much water per acre as we were 30 years ago.”

FID and Middle Fork systems now are almost completely piped. The Dalles entire system is piped and pressurized. The most gains will come from piping East Fork’s remaining canals.

Districts encourage using micro-sprinklers or drip irrigation and installing soil moisture probes. Just as farmers are becoming more efficient, a new water user is converting farm land.

In a subdivision west of Hood River, a home owner waters lawn and pavement mid-afternoon on a 101 degree day with irrigation water.

Rural residential. Irrigation districts formed to provide water for crops. But throughout Oregon and Washington farms are sold and subdivided into residential developments. The water right attached to farmland passes on to the subdivision. Whatever that amount was now must be divided among the residential parcels, the water now used for landscaping and lawns. Half of Farmers Irrigation District’s 1,850 accounts are now small parcels: 338 of them within the City of Hood River.

Unlike in cities where each molecule is metered and the owner charged accordingly, irrigation districts charge a flat fee. So there is no incentive for rural residential users to use water conservatively. Some may, but overall residences use more water per land area than agricultural users.

While the obvious solution would seem to be to put in meters, Perkins said that meters require more maintenance and staff time. Already, he says, 70 percent of their summer staff’s time is spent dealing with small land holders.

Future: If scientists’ predictions hold, in eighty years only four percent of Mt. Hood’s current glaciers will remain. Hood River valley irrigators’ plans are already underway. Farmers Irrigation is raising Kingsley Reservoir eight feet. Middle Fork hopes to raise their Lawrence Lake Dam three feet. East Fork hopes to have their systems piped by 2040, and reservoirs built. The Dalles Irrigation District is not worried, they don’t see the Columbia River running out.

Outside the reach of irrigation districts, wells have provided water. With wells, orchards and vineyards supplanted dryland wheat, sagebrush, cattle grazing. Well owners, too, have water rights, but a 2016 Oregonian series,‘Draining Oregon,’ showed that the state is giving out more water rights than are available, causing water levels in aquifers, streams and neighbors’ wells to drop. Cherry orchardist Omeg said their well that for decades has provided 1,500 gallons per minute now delivers 600.

Cities guard their water supplies. They have the most voters who can pressure lawmakers to put their needs above salmon and agriculture. While irrigation companies work to be efficient they are clear that in a severe drought, their duty is to serve patrons first. That would leave fish in a bad place. Irrigators dewatered part of the Deschutes River three years in a row stranding fish. Volunteers using buckets and nets rescued as many as they could.

“Water is a resource we can’t live without,” said The Dalles Irrigation’s Saldivar. “If we continue to not respect the resource, it won’t be around in the future. We’ll run out.”

Learn about your household’s water foot print by using a water calculator like this one from Grace Communications Foundation: http://www.watercalculator.org/complete/

RELATED POSTS

Good wake up consequences! Should we send it to Trump and all his supporters?

Great to hear from you, Peg. Keep those comments comming.