The United States and Canada have announced a tentative agreement that updates the 60-year-old treaty. Critics say it’s “business as usual”

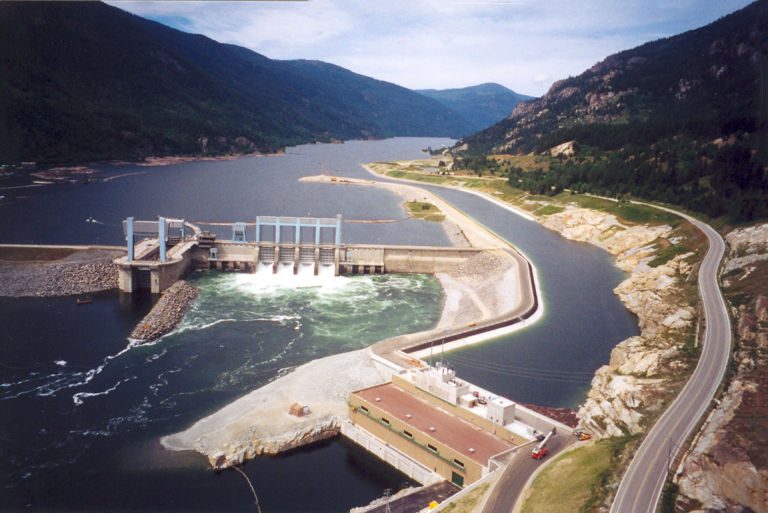

Collect and control: Completed in 1967, the Duncan Dam in the Purcell Mountains is one of three dams in British Columbia built as part of the Columbia River Treaty. Photo: Wikicommons

By Kendra Chamberlain. July 17, 2024. The United States and Canada have spent the past six years reworking a half-century-old deal between the two countries that outlines how the Columbia River is managed for both flood control and hydropower generation.

After 19 grueling rounds of negotiations, the two parties have announced that an agreement on the Columbia River Treaty has finally been struck.

The “agreement in principle,” released July 11, offers a rough outline of provisions of the treaty that will be updated. The final version will hold for 20 years before it can be revised.

“After 60 years, the Treaty needs updating to reflect our changing climate and the changing needs of the communities that depend on this vital waterway,” President Joe Biden said in a statement. “In the coming weeks, the United States and Canada will continue our work together to draft a Treaty amendment that reflects these key elements and to begin the process in both our countries to get this done.”

The two countries have agreed to tweak what’s called the Canada entitlement, a provision of the current treaty that sees a portion of hydropower generated in the United States sent to Canada in exchange for keeping some water stored in reservoirs on the Canadian side of the river to help manage flood risks across the border.

While the treaty doesn’t technically have an expiration date, its flood management provisions expire in September.

The update will see a 50% reduction in power the United States sends to Canada by 2033. The United States will have access to “reservoir storage space” behind Canadian treaty dams for flood management, but will have to fork over roughly $37 million over the next 20 years, according to the Government of British Columbia.

The Columbia River Treaty was originally signed in January 1961 by U.S. President Dwight Eisenhower and Canadian Prime Minister John Diefenbaker.

Noticeable omission

Tribal and environmental groups have been hopeful the negotiations would offer an opportunity to inject into the treaty more safeguards for the Columbia River and its overall health.

The treaty was negotiated without any tribal input and does not reflect tribal interests, nor the needs of the river or its fish, according to the Columbia River Inter-Tribal Fish Commission (CRITFC).

For the last decade, the commission has been pushing for an ecosystem-based function management approach within the treaty that would prioritize things like increased spring and summer flows, restoring fish passages and reconnecting floodplains.

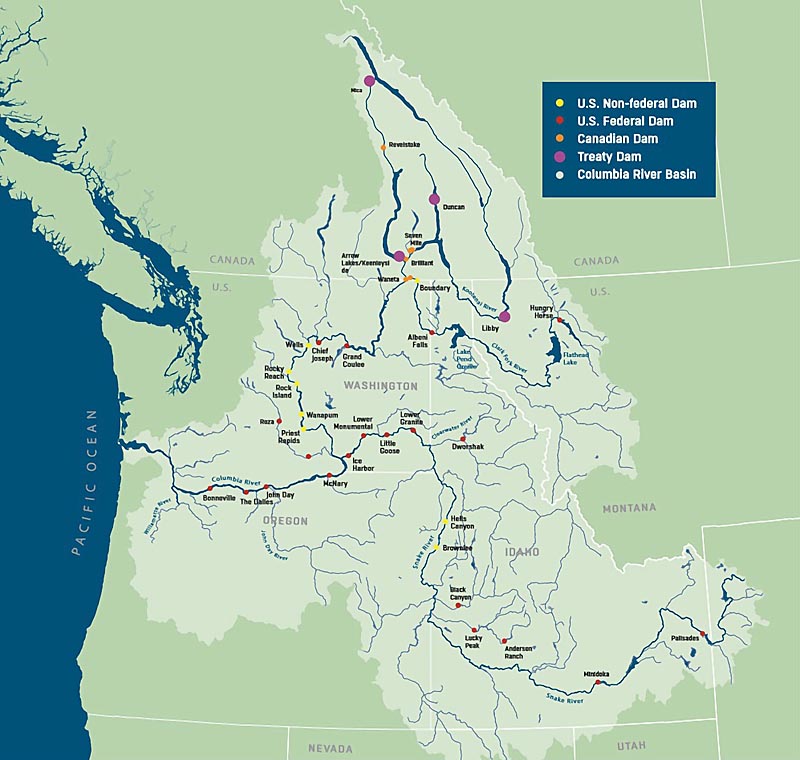

Columbia River Basin and Columbia River Treaty map. Source: Save Our wild Salmon

More recently, the Columbia River Treaty Non-Governmental Organization Caucus, a body of 10 organizations, joined CRITFC in calling for ecosystem-level function to be included as one of the primary purposes of the agreement.

Doing so could ensure the river’s overall health has equal footing in the agreement alongside hydropower generation and flood management.

“That was noticeably omitted,” Joseph Bogaard, executive director of Save Our Wild Salmon and chair of the caucus, told Columbia Insight.

Bogaard wrote an op-ed for Columbia Insight last year explaining the caucus’ hopes for treaty modernization.

The group expressed disappointment that the new agreement doesn’t include provisions to ensure the health of the river and fish.

“The view from our community’s perspective is that the agreement in principle reflects a continuation of business as usual as it relates to economic interests in the Basin and salmon—notably endangered salmon who are struggling for survival today,” said Bogaard.

The update will establish a new tribal and Indigenous-led body to offer recommendations on how to better support Indigenous cultural values.

The update also commits to sustaining “healthy” salmon populations by maintaining minimum flows during dry years to ensure salmon can complete their annual migrations.

But Bogaard said the update doesn’t do enough to protect the river or its fish.

“The power and flood interests get priority, and salmon seem like an afterthought,” he said. “And, of course, many of these [salmon] populations have already been lost, and those that remain, for the most part, are at risk of extinction.”

The final agreement will need to be approved by the U.S. Senate and the Province of British Columbia before being enacted.

Hi Kendra- I wanted to make sure that you knew that Joseph Bogart and I wrote an op-ed on the CRT a little while ago (that was published in the Everett Herald) that expressed specific concerns on what we anticipated would be impacts to salmon from new treaty operations. It seems like those concerns are still valid from the extant information from the AIP offered by the US DOS. If you haven’t seen the op-ed I would be glad to forward it to you.

I represented the CRITFC tribes as a technical advisor during regional discussions that led to the US Regional recommendation for modernizing the treaty. I hope to hear from you soon. The CRT modernization is of immense importance to the region and more information needs to be widespread so that the public- who have largely been shut out of the process- become aware and be able to influence it into the future. – Bob Heinith