By Jim Drake. March 21, 2019. Imagine not only choosing a neighborhood you’d like to live in, but actually creating the neighborhood you’d like to live in.

Imagine writing down your values, needs and expectations of a lifestyle, and then sharing them with like-minded people who want the same.

Cohousing — intentional collaborative housing that fosters a sense of community — has already been integrated into many urban and rural areas of the United States, as well as in other parts of the world.

Now the idea is beginning to take root in the Gorge.

Communities under development

Since 2016, experts in the cohousing field have visited Hood River, expounding on the benefits and challenges of creating an intentional cohousing community. Past seminars have featured architect and noted cohousing author Charles Durrett, as well as Seattle’s architect and community planner Grace Kim.

Kim, who is actively involved in designing a cohousing community in Hood River, lectured at the Columbia Center for the Arts to a capacity crowd in January. She has given a number of presentations on the topic, including a talk that was featured at the 2017 TED conference in Vancouver, British Columbia.

The seminars in Hood River were initiated and presented by Gorge Cohousing, a core group of interested persons that has since developed into two entities: the Adams Creek Cohousing group in Hood River, Oregon and the White Salmon Cohousing group in White Salmon, Washington.

Gorge Cohousing founder and Adams Creek member Nashira Reisch says that although the Gorge does have some restrictive land use laws, she believes there are people who are attracted to strong community connections and want to be good neighbors to each other.

“Creating a cohousing neighborhood is worthwhile for people who value living in a community with a deep sense of place and connection with their future neighbors,” Reisch says.

Noting that cohousing projects can be developed just about anywhere, she believes there is a unique culture in the Gorge that makes cohousing a viable choice.

“It will take creativity and lots of work. We have learned the limitations and opportunities but speaking practically, we need to align with zoning, land use laws, and neighbors’ concerns. So, while we may have physical restrictions on where a cohousing neighborhood can be built, we also have the type of people with the spirit to make it happen.”

The Adams Creek Cohousing group has moved forward with a two and one-half acre land purchase on Sherman Ave. in Hood River. The group’s goal is to support at least 15 households, with an upper goal of 30 households.

Still in its formative stages, The White Salmon Cohousing group is currently researching and evaluating land options. That task has fallen to Bruce Bolme, a member of the Development Committee, who says there is an enormous amount of procedural work ahead because most of the land he has surveyed has special considerations.

But to Bolme, these considerations are not barriers.

Bruce Bolme surveys potential land for the White Salmon cohousing group within the city limits of White Salmon. Photo by Jim Drake.

“Since we’re looking inside the city limits, the Gorge National Scenic Area restrictions are not going to be a concern. But from what I’ve heard it’s still an enormous amount of plans and permits and regulations to follow. One homesite is near a seasonal creek and surveys have to be done to prove it’s not salmon bearing. One of the sites has a lot of trees, and there would have to be a squirrel habitat survey. These are all things that are an obstacle course, but you just run them, they’re not intractable barriers, they’re just things you have to slog through,” Bolme says.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“If you persevere, you’ll figure out something. You don’t lose unless you quit.”[/perfectpullquote]

Cohousing communities allow individuals to own their own home, just like a private home or condominium. But cohousing fosters a deeper sense of community by sharing the cost of land and common use buildings, which usually contain a large kitchen, recreation and storage rooms.

The community is laid out and designed according to the owners’ core values, and community interaction is at the heart of most designs. Owners interact with one another by sharing vehicles, making community meals on a rotating basis, and helping with maintenance, gardening and even tasks like babysitting.

Replicating many aspects of a traditional village, the first cohousing community was started in Denmark in the 1960s. Since then, they have grown in popularity due to their ability to provide a supportive lifestyle for the young, the aging, and anyone in between.

[robo-gallery id=”10769″]

As one can imagine, creating a cohousing community is a daunting task. Getting a group of people to decide on community values, the type of housing, the land and location, as well as the financing, is a work in progress for both groups. But, with a regular business meeting schedule and potluck gatherings in living rooms and local grange halls, gradual work in the form of committees and action plans are chipping away at the goal of moving in.

Kalama Reuter, who is leading the White Salmon membership committee, says that the energy for drawing people in comes from “deep down commitment.” Reuter moved to the Gorge in 2005.

“Our group created a financial questionnaire, and it took me at least half a day to figure out if I could get a mortgage on my house and figure out what is my real capacity here. To sort that out takes some commitment in the first place. With a group like this, you have to really take time to develop those relationships. And then there’s this whole thing of can we all be interested in moving toward the same property. I mean, it’s huge,” Reuter says.

The White Salmon Cohousing Group is seeking 12 to 20 households to participate.

Model communities

Reuter has close friends who were involved with a cohousing group called Songaia, located in Bothel, Wash. After an original group was established, two satellite groups eventually formed, each learning the building process from one another.

The Songaia cohousing community features a communal garden, and is made up of 13 homes on 10.6 acres. Photo courtesy of Songaia

“Hopefully our process was a little simpler, because we’re kind of feeding off of the pioneering of the original Gorge Cohousing group. We’ve already saved a lot of money setting up the LLC, because they had already hashed through some things, so we could just basically copy it,” Reuter says.

And Reuter has lots of ideas for what her ideal cohousing experience would look like.

“I want a low carbon footprint, I want to do things conscientiously and I want to make room for recycled materials.”

She also wants intense sharing.

“Nobody should have a washing machine in their house, it should be in the common house. It’s not like I can dictate what somebody else is doing, but I really want to encourage community. The more we share, the more we interact,” Reuter explains.

“The White Salmon group is still finding our space, our people, and our land. I feel that most people just want a basic affordable house and some sense of community. We have talked about how many meals a week do we want to share, and that might be a dividing line, too. That’s the thing…there’s such a range of potential under this umbrella,” Reuter says.

“It will be kinda like a miracle when it’s done.”

For both cohousing groups, environmental building and lifestyle concerns are priorities.

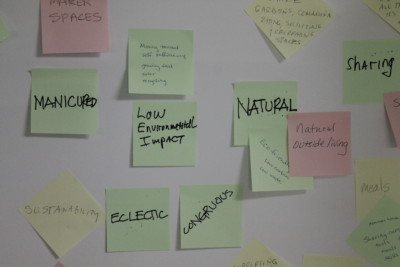

Examples of some of the shared values of the White Salmon Cohousing group. Photo by Jim Drake.

Heidi Venture, who serves on the Process and Steering committees for White Salmon Cohousing, says a lower impact on the environment is one of the most appealing aspects of cohousing.

“In these communities, people share cars. Instead of having 20 cars for 20 households, maybe they only have five. We’re thinking of having two electric vehicles to share. If people need a car for a vacation, they may be able to rent one for a long trip,” Venture explains.

Venture says that the emphasis on environmental stewardship can even be found in the reduction of rooms needed in each private house.

“If everyone is sharing a common house with guest rooms, that means that the community has saved all of the associated costs of trying to build a guest room in each house,” she says.

“You can have a house that meets your own needs, a one bedroom, 800 sq ft house, instead of a 2-3 bedroom, 1,500 sq ft house. You’ve not only saved all of those building material costs, the environmental impact of making those materials and transporting them, you also save the ongoing maintenance costs of heating and cooling that space.”

John Boonstra is on the Energy and Environmental Committee for Adams Creek. He says the group has received input from the Energy Trust of Oregon and the Hood River Energy Plan, with the goal incorporating net-zero building strategies.

“A main goal for Adams Creek is not to use fossil fuels. For some people, it takes a lot to give up the gas flame for cooking. We’re talking about inductive cooking, which has been happening in Europe. We’re trying to learn about a lot of things,” Boonstra says.

“We are aware of the fact that we’re building something from scratch, and that we’re going to be in a place where we can think about long term future. We’re astutely aware of what’s happening to the climate, what’s happening to the world. So we want to be responsible for creating something net-zero energy ready.”

One example of a net-zero cohousing community is Ankeny Row in nearby Portland, Oregon.

A common courtyard at the Ankeny Row cohousing community in Portland.

Dick Benner has co-authored a book about his experience developing Ankeny Row, and he has lived there for four years now.

“Everybody in each of the units is getting to net-zero and this is attributable to the passive house construction and the photovoltaics used to generate all of our electricity. I didn’t know this at the time, but if we generate a surplus, instead of PGE writing us a check, our surplus goes to low income families. I had no idea about that,” Benner says.

Benner says the group at Ankeny Row was in agreement on how to build for net-zero energy use, but that it wasn’t a cheap way to build.

“We didn’t really know what to expect on net-zero. The way the modeling was done for us by Greenhammer, our developer, they assumed four people would be living in our townhouses that have 3 bedrooms, so they prescribed 13 panels per unit. And then, we got into trouble with rising costs. We were trying to bring the costs down by $500,000, which turned out to be crazy, we couldn’t do that. But we did change some decisions that bought it down by $200,000.”

Benner says that a review of past energy bills and records was factored in to see if the number of photovoltaic panels could be reduced even further.

“After reviewing our past bills in most of the places that we previously lived, they said we’re pretty sure we only need 12. So we were a little anxious if we were going to make it. Our unit generates about 3600 kilowatt hours per year, and we use about 2000 kilowatt hours per year. So we think we could have done with 10 panels.”

The townhouses of Ankeny Row.

He says that two of the households in Ankeny Row are looking into purchasing electric vehicles, which will put more of a strain on the system. Fortunately, there’s still room for more panels on the roof.

“We’ve got roof capacity to add six more panels, so if more partners go all-electric, then I think we can generate enough to charge the vehicles,” he notes.

Benner stresses that although the goal of net-zero was important, his personal experience of living in a community that he helped design, plan and create has had a profoundly positive effect on his life.

“I can say without reservations it’s the best living arrangement I’ve ever been in,” Benner says.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]“I’ve been around neighbors all my life — with my folks, on my own and with my own family. But here, all of my neighbors are friends. It’s just amazing. And I think they’d all agree. There’s just no question about it.”[/perfectpullquote]

Moving forward

Both the Adams Creek and White Salmon cohousing groups have indicated that local government has been supportive of the cohousing efforts so far.

“One of the best things I’ve learned is the White Salmon mayor is excited about it, and for the city in general,” Bolme says.

Bolme is even investigating a land trust option, which may be a way to help low income people with cohousing.

“I believe that if someone cares enough to make the effort, that we can figure out a way they can work with us. I just don’t know how it would be, we would just have to figure it out and negotiate. But I’m optimistic that it’s doable.”

Nashira Reisch says that Hood River has also welcomed the idea of cohousing, and that the group has already cleared a large hurdle by purchasing suitable land.

The Adams Creek Cohousing property occupies 2.5 acres on Sherman Ave, in Hood River, OR. The group is debating whether or not to keep the existing structure,or start over, making the most space for private houses and a common building. Photo by Jim Drake.

“Some of the aspects of the design, such as pedestrian walkways protected from vehicular traffic, line up nicely with some of the long term goals the city has for walkable and bikeable routes in our community,” she says.

A prevalent cohousing theme is sharing and reducing the need for duplicate items. Examples could be as detailed as the number of lawnmowers, snow shovels, or tools a community needs, or as general as how many meals the community shares in a week.

“Grace said they have a meal together every single night in her nine-household cohousing unit. So she ends up cooking two or three times a month, and she just has to come in and enjoy the rest of the time. When cooking for a big group like that, they’re going to buy in bigger quantities, they’re going to buy packages that use less plastic. They’re going to have less waste, and they’re going to have a system for dealing with waste, a composting and recycling system that everyone buys into. They’re all in it together, so you’re able to do more,” Venture says, referring to the influential talk that Grace Kim recently gave in Hood River.

Both cohousing groups continue to schedule regular business meetings and committee meetings, as well as potlucks to gather and discuss everything from group core values to developing guidelines for group membership. Adams Creek recently held a members-only planning session with architect Grace Kim, which focused on designing the common house.

“I would say we’re definitely in the design phase for this neighborhood,” Reisch says. “We learned a lot from authors Kathryn McCamant and Charles Durrett, who wrote the book ‘Creating Cohousing’.”

Founding member of Gorge Cohousing Nashira Reisch, center, with her family. Photo by Jim Drake.

Reisch explains that in terms of cost, the Adams Creek project will likely be close to the market rate for Hood River. The White Salmon group, now in the exploration and formative stage, is striving for affordability, according to Bruce Bolme.

“We’re just getting started, but we do know that the social structure is just as important as the physical structure,” Bolme says.

“We want to learn what our social structure will be by getting to know each other, and then we’ll better be able to design the physical structure to be a custom fit.”

Upcoming events

National Cohousing Open House Day: April 27

2019 National Cohousing Conference: May 30-June 2 at the Hilton in downtown Portland

Adams Creek Cohousing will continue to host informal cohousing conversations at Dog River Coffee in Hood River. Every second and fourth Sunday of the month at 1pm. For membership questions, email: bek4garden@gmail.com

White Salmon Cohousing will host potluck gatherings on the first and third Sunday of each month. For membership questions, email: kalama@embarqmail.com

I have a lot of concerns about using Ankeny Row as a model. We have a desperate affordability problem in this country and especially in urban areas on the West Coast, and especially in Portland and Hood River. Making something “sustainable” that costs $750,000 is, well, absolutely NOT sustainable!! What’s the single biggest indicator of the size of someone’s carbon footprint? Wealth!! If we make low-carbon or net-zero a privilege that only the wealthy can afford (and that other people get wealthy selling), we can pretty much kiss the planet good bye. And any pretence of advancing justice or doing the right thing.

There’s an Italian company called MADI that can build and install a three bedroom home on either a temporary or permanent foundation anywhere in the world for $130,000 USD. 2 and 1 bedrooms are, of course, less. The homes are already EU energy class B and can be upgraded to A or A+++, and be ordered with solar. Plumbing, electrical, and HVAC are pre-installed. Putting two of these on each 5,000 sq ft lot could enable a mix of owners and renters in a community, at far less than current “market rates.” (Most potential owners who aren’t already above the median will need access to traditional mortgage financing.)

I would like to learn more about groups looking to form communities that value economic, social, and cultural diversity, as well as resource conservation and sustainability, and oppose gentrification and displacement. Zero-energy homes for wealthy white people, in what was once Portland’s African-American community, falls short. I hope these emerging communities in the Gorge can find better role models.

Hi Jay, I just read your comment on the https://columbiainsight.org/cohousing-emerges-in-the-gorge/ website and couldn’t agree with you more. I’m pasting in the text of an email I just sent out to a couple of eddresses I found on this site as well. Trying to figure out/hoping that the White Salmon effort is still happening. Would love to hear back from you if you know anything and also will look into MADI construction you mentioned. Interesting.

Hi!

I’ve just tonight found out that there is a group in White Salmon who is working to build a co-housing community. Recently I also learned about Adams Creek in Hood River. I’m now getting there new letter and will visit one of their events in October.

I’m a several years member of FIC and am in the process of researching, sorting, investigating, narrowing, widening, etc. the possibilities in an effort to find the right fit for living the next phase of my life.

What I most clearly know is that I really want to live in community. I sold my property nearly 2 years ago and hit the road in a short school bus conversion last November. No surprise to me, I don’t really want to just travel around. But it’s a good way to house myself and to be able to visit communities until i find the right fit to put down more solid roots. I have a desire and need to expend my energy in a way that is helpful and beyond ‘self’. I adore living small, that’s been a wonderful part of living in a 5 window long Skoolie. So best case would be finding a tiny house co-housing community or someone to share a small house with. I’m a native Oregonian and have lived in the PNW most of my life. So many IC’s are in the east and south, but I don’t want to go there.

So no need at this point to tell more of my story. What I’d love is to be on any info distribution lists, emails, etc. I’m currently spending [too much] time in Seattle and Vancouver however I have been needed to support the care needs of a few friends, so here I am. I’ll spend most of October in the Vancouver WA area. Would love to meet up with someone who is involved in this community development and find out more.

Stay amazed, Be Kind,

Best Regards,

Joyce

Hi Joyce (and everyone!) I just moved into my school bus Ive been converting for over a year and in the most sustainable way I am able. Im looking for intentional living community. Have you found any in WA who are welcoming of skoolies? Thanks for your time!

In solidarity, rage, and inspiration,

Forest Ember