Rick Morck stands by one of Threemile Canyon Farms two clarifers. Behind it, stand some of the farms’ 25,000 dairy cows.

Everything about Threemile Canyon Farms is supersize. It covers 40,000 acres near Boardman, Oregon; raises 25,000 dairy cows which produce 130,000 gallons of milk– every day; grows 230,000 tons of potatoes a year; and 8,000 acres of organically certified vegetables. It may be the only gated farm in the Northwest and one that has a security guard station at every gate.

And in the center of the farm, Threemile harnesses micro-organisms to produce 4.8 megawatts of electricity: the equivalent of three wind turbines.

Three years ago, the farms’ owner Ron Offutt and General Manager Marty Myers installed an anaerobic digester–a source of renewal energy. Their expectation was that the digester would generate sufficient revenue beyond repaying their investment to significantly reduce their electric power costs.

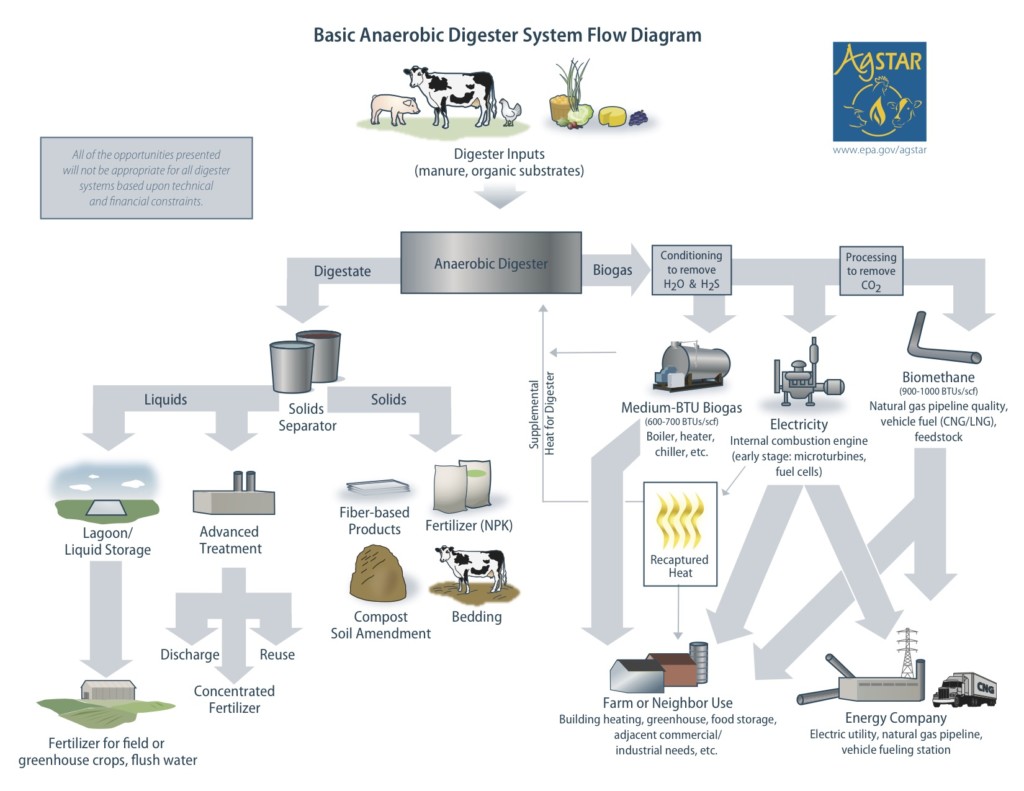

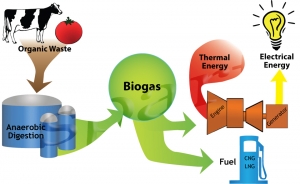

An anaerobic digester works somewhat like a compost bin. In a compost bin, you toss in organic material like leaves, vegetable and fruit scraps, bacteria break it down, and out comes humus so good for growing plants.

In anaerobic conditions, organic material is similarly broken down, but it’s done in an enclosed container without oxygen. In these conditions, bacteria give off methane and carbon dioxide. Methane can then be burned to run generators and create electricity. While this takes a lot of organic material, Threemile’s dairy has lots of cow manure.

Anaerobic digesters offer so many benefits, it’s surprising how little the public knows about them. In a dairy operation like Threemile’s, digesters take unwanted waste, manure, and create valuable energy. Plus they keep methane, a greenhouse gas, out of the atmosphere.

Anaerobic digesters offer so many benefits, it’s surprising how little the public knows about them. In a dairy operation like Threemile’s, digesters take unwanted waste, manure, and create valuable energy. Plus they keep methane, a greenhouse gas, out of the atmosphere.

Methane has a global warming potential 23 times that of carbon dioxide. “When combusted, each molecule of methane is converted to one molecule of carbon dioxide; thus reducing the global warming effect by 96 percent.” US EPA http://www.epa.gov/climatechange/ghgemissions/gwps.html

Threemile’s owner, Ron Offutt, was initially skeptical of the project, Meyers says. “But he trusted that we were doing the right thing. He thought that we had the right people and the right location, that if we couldn’t make it work, nobody could.”

The right people. Meyers the right people included Jerry Trotter, R.D. Offutt Co.’s Director of Engineering, Tom Chavez, Columbia River Dairy’s Wastewater Manager and, at nearby Finley Buttes Landfill, consultants Rick Morck and Gerry Friesen. Rick and Gerry had developed a successful system taking the landfill’s methane to generating electricity. Because of Threemile’s scale, it took a team to design and build a digester complex made up of four digesters. When the project went live in 2012, Meyers asked Rick and Gerry’s company Threemile BioEnergy, LLC, to operate and maintain the engine-generators and biogas system while Columbia River Dairy continues to operate and maintain the manure handling system.

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

Making it work. A digester at a dairy can be a pretty simple operation. Send manure into an airtight-oxygen free container. Allow the matter moves slowly through the digester–giving time for bacteria to break it down and give off gasses. Siphon off the gasses. Burn methane in a generator to create electricity, send electricity to the grid just like energy from turbines in fossil fuel plants, dams and wind towers.

Like wind and solar, anaerobic digestion is a renewable energy source, but it has the same advantage as hydro and fossil fuel in that it is a constant. Cows create manure 365 days a year.

But Threemile’s digester, far from being simple, is elaborate, not because of size; but because of water. Threemile is a flush dairy. They use water to wash manure off the alleys where the cows feed. The flush–manure and water–is piped to two tanks, called clarifers.

In the clarifiers, suspended materials settle to the bottom and excess liquid flows over the top to be recycled to the barns for flush water. The settled material goes into the digester. There bacteria go to work breaking down the material and releasing gasses, which are piped to Threemile’s six generators. The water and solids coming out of the digester are separated: water goes to fertilize crops and the solids as bedding for the cows.

Meyers points out that the energy created by putting manure through the digester and taking energy off it doesn’t change its nutrient value. The liquid still contains nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium plants need. It goes through their irrigation system and on to the crops reduces the amount of fertilizer the farm has to buy.

How much power?

When running at full capacity, Threemile’s digester complex produces 4.8 megawatts, which provides 30 percent of the farms’ energy demands for dairy and irrigation operations.

Irrigation uses a lot of energy. “We get 8 inches of rain a year here and it all comes in December through February,” Marty says. Those acres and acres of crops require a lot of water, which must be pumped. Pumping equals electricity demand.

Meyers’ eventual goal is for the farms to be totally self-sufficient on power. Right now it costs Threemile 8 to 8.5 cents per kilowatt to produce power. They can buy it for around 6 to 6.5 cents per kilowatt. Even though it costing more now, he’s certain that the cost of bought power is going to go up.

All of the power Threemile generates is sold to Pacific Power and then Threemile buys it back. “Whether the electrons leave the property or not is a debate. Right?” Meyers laughs.

The investment

The digester project cost $31 million. Threemile was ready to build when the American Recovery Act was enacted in 2009. Because Threemile was creating renewable energy, they were eligible for federal grants covering 30 percent of the total investment. Not all of the $31 million cost was eligible, but Threemile received about $6.6 million to offset construction cost. Oregon’s Business Energy Tax Credits (BETC) further reduced the cost.

Once the system began operating, Threemile’s energy production was eligible for biomass tax credits through the Oregon Department of Energy. Meyers is currently working with the Oregon Climate Trust to sell carbon offset credits.

“We got it to the point with all these different programs to where we could at least break even and service the debt that we took on to build the project,” Meyers says “And we felt that opportunity was kind of a onetime opportunity, because all these programs came together at once.”

The ecological circle

Meyer and Morck are proud of the digester system. It’s met their energy and financial goals and it was a proved to be a link to complete what Morck calls: the ecological circle.

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

“It’s this complete cycle, because the ground grows crops; a bunch of those crops come back as feed for the cows. The cows produce milk. That’s one stream,” he says. “The cows produce manure that gets processed and goes back onto the fields as fertilizer to grow more crops. And then this project is sort-of dropped into the middle of that manure processing and now extracts energy out of it as well.

“Which then is substituting for some other hydrocarbon fuel that’s being burnt to create electricity,” Meyers says. “So it’s truly the environmental footprint that you’re looking for, and actually lessening our impact.”

“There’s not a single waste stream that leaves this facility,” Rick Morck says, “short of the permit we have for releasing our exhaust gases from burning biogas in the engine.”

What a fascinating article. So inspiring to see such a full circle operation dedicated to becoming self sufficient. Let’s hope we see more of this in the future. I wonder if the owner would be willing to give presentations to other agricultural businesses.

We agree, Nicole.