The Humming in the Flowerbeds

240,000 species of known flowering plants exist on planet Earth. Of these, 180,000 (75%) must form a partnership with pollinators to complete their reproduction. Alfalfa, clover, hay. Apples, cherries, plums. Lavender, sage, almond. Celery, cucumber, squash–pretty much every plant we like to eat needs to be pollinated.[1].

[media-credit name=”Jurgen Hess” align=”alignright” width=”267″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

In other words, without pollinators, we and our livestock would starve. Our agricultural economy would collapse, sending ripple effects through every other sector. Right now this economy is a house of cards, dependent as it is on one species of pollinator – Apis mellifera, or the European honeybee, introduced in North America in about 1620?[2].

In 2006 we woke up to the prospect of a world without this pivotal aide when colony collapse disorder swept the country, killing millions of adult honeybees. Winter bee deaths in commercial colonies reached 33 percent in 2011–double the previous historical rate [3]. Since then we’ve learned that colony collapse disorder is probably the result of several different influences on honeybee health. Parasites, fungi, viruses, pesticides and the stress of being moved from site to site during pollination season are all likely contributors to honeybee declines. Today fewer bees are expected to work more: In 1947 the U.S. had about 6 million honeybee colonies, compared to about 2.5 million today.

Moreover, says OSU entomology professor Andy Moldenke, modern commercial beekeepers breed their queens with very few males, rather than the many available to wild bee queens, which radically reduces the genetic diversity of the commercial bees’ offspring. This in turn limits the ways they can adapt to changing conditions and handle stress. Moldenke feels that this narrowing of genetic possibilities is at least as important to bee declines as pesticides.

Honey, Bumble, Sweat and Leafcutter

And it’s not just honeybees under stress.

Native bee species have also declined drastically since Europeans arrived in North America. For example, the Willamette Valley, before Europeans arrived, had one of the densest concentrations of pollinating bees anywhere on the planet–some 350 species, according to Moldenke. He estimates there may be only 50 and 75 species left. “All the meadows were plowed up and turned into agricultural fields,” he says. “If you lose the habitat, you lose the species.”

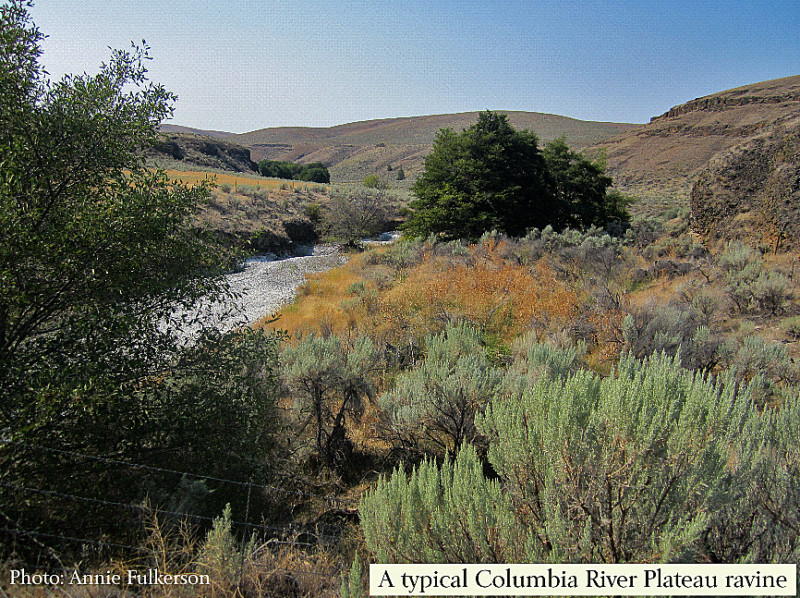

For places like the Columbia River Gorge and the Oregon coast, Moldenke says, there were always fewer species of pollinators because the climatic conditions, high winds and fog in particular, are difficult for bees to handle. The most important pollinator for these areas was the western white-tailed (or ‘white-bottomed’) bumblebee considered extinct since the 1990s, but was sighted in the Seattle area in 2012 and 2013 [4]. The cause of its disappearance is thought to be a Nosema fungus introduced with imported European bumblebees. For this reason, in 2012 the Oregon Department of Agriculture formally banned importation of exotic bumblebees.

[media-credit name=”Jurgen Hess” align=”alignleft” width=”345″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

We still don’t know exactly what is happening to honey bee colonies. But, the crisis has triggered a general reappraisal of our dependence on pollinators and a re-examination of some other types of bees that could ease the situation. For example, Moldenke says, honeybees are terrible at pollinating blueberries, so some farmers are growing blackberries along the edges of their blueberry fields to attract bumblebees, which will pollinate the blueberries. Other insects – moths, ants, wasps, beetles, and butterflies – as well as birds, lizards and mammals pollinate. A species of wasp pollinates figs. Bats pollinate balsa and other related trees. Hummingbirds pollinate many flowers and shrubs.

Not all large bees are bumblebees, says Moldenke. “Most of the other large bees are no-nonsense bees,” Moldenke says. “They fly like hummingbirds or special helicopters, whereas bumblebees sort of bumble along.” Bees that might be mistaken for bumblebees include sweat bees (so called because they like to lick the sweat from human skin) and carpenter bees (which people fret may damage wood structures).

Pesticides

The issue of bees and pesticides is a vexed one, particularly after the widely-publicized bee deaths from neonicotinoid insecticides in Oregon. Last summer Portland experienced at least three mass bumblebee die-offs [5]. In 2013 some 50,000 bumblebees died in Wilsonville after linden trees in a store parking lot were sprayed for aphids. The spray, called Safari, has a neonicotinoid principal ingredient. Structurally similar to nicotine, neonicotinoids are thought to be a major influence in bee deaths around the world. They are neurotoxins, so they destroy insects’ nervous systems; they’re water soluble so they are taken up by plant tissues including nectar and pollen; and they are persistent in the environment.

Steve Castagnoli, OSU Extension Horticulturist for Hood River County, works with fruit growers in the Hood River Valley. He encourages the application of integrated pest management principles to “minimize the use of pesticides.” He says that most orchardists are “cognizant that caution needs to be used whenever there are bees around.” Local pear growers, for example, don’t use neonicotinoids for this reason, he adds.

Still, “Acute and sublethal effects of pesticides on honey bees have been increasingly documented, and are a primary concern,” wrote the U.S. Department of Agriculture in 2012. Bees are hammered by multiple chemicals – 161 different pesticides have been found in honeybee colonies [6]. We can assume that any native pollinators that frequent agricultural areas are subject to the same devastating threats. Even if pesticides don’t kill bees outright, they stress bees’ immune systems, making them less able to defend against pathogens like fungi and viruses.

[media-credit name=”Jurgen Hess” align=”aligncenter” width=”436″] [/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

What’s Being Done?

As usual with environmental matters, it is not clear whether human society can change fast enough to avert disaster. But some steps are being taken. In response to the bumblebee die-offs, Oregon Governor Kate Brown proclaimed August 15, 2015 Oregon Native Bees Conservation Awareness Day [7]. In February 2014, the City of Eugene banned neonicotenoids on city property – the first city in the nation to do so. Last spring Portland did the same, bringing the total to eight cities in the U.S. to take this step. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service will stop using the chemicals in national wildlife refuges by January 2016 [8].

Lisa Arkin, executive director of Beyond Toxics, an activist group based in Eugene, says people have misconceptions about bees that hamper their understanding and appreciation of them. Beyond Toxics has partnered with the Xerces Society, which is dedicated to stopping the headlong rush to extinction of all kinds of invertebrates, to recruit people to host beehives in their yards.

“When we first started this campaign and wanted Eugene to ban neonicotinoids in city parks, the response we got from [city] staff was, ‘We can’t help bees because people are afraid of bees.’”

But, Arkin stresses, “Bumblebees and honeybees rarely sting. It’s wasps and hornets that sting.” Once people understood that, she says, resistance to bee protection and the pesticide ban evaporated.

What You Can Do

“The easiest and most straightforward way to manage for bee diversity is to maintain or augment flowering plant species diversity. [9] ” The Bees of the Columbia Basin, V.J. Tepedino & T.L. Griswold

Fortunately there are things you can do to help bees. There are two native plant nurseries in the Columbia Gorge; Humble Roots Nursery [10] in Mosier, OR and Milestone Nursery in Lyle, WA, that stock pollinator friendly plants. If you think you might like to host someone else’s honeybees in your yard and maybe get a bit of honey out of it, here’s Gorge Grown’s list of bee resources [11]. If you have an unwanted swarm, contact Grow Organic to arrange a pickup by the Gorge Beekeeper’s Club [12].

Another thing you can do is create nesting sites for bumblebees, mason bees, and any other native pollinator. This guide from Iowa State University is helpful [13], with a couple of caveats: 1) PVC piping is not a good idea, as it very likely contains bisphenol A and some type of organotin compound. Both of these widely used industrial chemicals are endocrine disruptors; 2) plastic pipes and straws, while they protect against moisture and other environmental insults, also raise humidity and encourage mold growth and mite infestation. A better guide is the Xerces Society one [14]. Here’s how to build a bumblebee nest [15]. Bumblebees like to nest in ‘disorderly’ areas full of loose soil and leaf litter, so maybe you don’t have to rake your flowerbeds to within an inch of their lives.

The Cowslip’s Bell

The pollinator crisis is one of those environmental issues that seems so urgent that immediate action at every scale is required. Even if you hate bees or they terrify you or yo’re allergic, you still can’t live without them. Unless we all want to be out in the fields and the greenhouses every day from February to October with a Q-Tip and a bag of pollen, it would behoove us to make bees’ lives easier as soon as possible.

Bees matter, and not just for their pollination services. They are symbols of industriousness, joy, and the wonderful peace of summer afternoons when the loudest sound is their humming in the flowerbeds.

Shakespeare understood this perfectly well:

“Where the bee sucks, there suck I:

In a cowslip’s bell I lie;

There I couch when owls do cry.

On the bat’s back I do fly

After summer merrily.

Merrily, merrily shall I live now

Under the blossom that hangs on the bough.”

Footnotes and further bumblebee resources:

[1] Status of Pollinators in North America

[2] History of Bee Keeping, USA

[4] Mysterious Reappearance of White-bottomed bee

[5] Mass bee die-offs in Portland, OR

[6] Pesticides found in bee colonies

[7] Oregon Gov. Brown, Bees Proclamation

[8] U.S. Fish and Wildlife stop pesticide use by 2016

[9] http://www.icbemp.gov/science/tepedino.pdf

[13]?Build Your Own Solitary Bee Nest

[14] Tunnel Nest Management, Xerces Society

[15]?Bumblebee Conservation- Build Your Own Bumblebee Nest

[16] http://www.icbemp.gov/science/tepedino.pdf

[18] Plants in the Intermountain West

[16]?Bumblebee Conservation Trust

[17] Guide to landscaping for bumblebees

[18]?Guide to plants for pollinators in the Intermountain West[/fusion_builder_column][/fusion_builder_row][/fusion_builder_container]

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]