Water Rights – The Pretzel Logic

By Valerie Brown. Feb. 6, 2017. By 2100 there will be next to no glaciers at the headwaters of the Columbia River in British Columbia. Mount Hood’s glaciers have already retreated by more than 61% over the last 100 years and will likely be gone by 2100 as well. Their loss will sharply reduce late summer water flow in the Hood River, right when growers need it most. Cities, too, will be thirsty and baking at the same time.

The John Day River in Eastern Oregon is used extensively for agricultural irrigation

The handwriting is on the wall: naturally frozen water is no longer going to be a storage mechanism for the Columbia Basin. Nor will we be able to store as much liquid water as we are losing in snow and ice. And most experts anticipate less overall precipitation, even if there are also more extreme precipitation events.

That’s about as much as we can predict about future water supply in a rapidly warming climate. In the new regime we are facing, how are we going to distribute water fairly among city and country, farm and factory? What adjustments to our current system of water rights will be necessary?

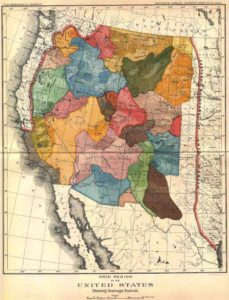

WATER RIGHTS HAVE A LONG AND WINDING PAST, and their future is likely to be similar. There was a chance for western water management to be set upon a rational footing in the nineteenth century after renowned geologist and explorer John Wesley Powell completed his ‘Report on the Lands of the Arid Region of the United States’ in 1879, in which he begged the nation to organize the region—including at least half the Columbia’s drainage from about The Dalles eastward—according to watersheds and not according to arbitrary political divisions.

Figure 1. John Wesley Powell Watershed Map. Image Credit: U.S. Geological Survey

Powell urged the government to ensure that water rights stayed with the land and that all landowners should be guaranteed access to water. He didn’t want entities like railroads and irrigation companies that had no particular interest in actually using the land to get hold of water rights. He even drew a map of his suggested organizing principle. (See Figure 1.)

Sadly, but not surprisingly, politicians and bureaucrats mostly failed to follow Powell’s advice. They were from the East, where water was almost always available from rain, springs, rivers and groundwater, and they used rules brought from Europe. These were usually riparian rights, where owners of land bordering a waterway owned the water rights. Perhaps more tellingly, American policymakers thought Powell’s ideas too regulatory, stifled free enterprise. Lawmakers also built into the system the right of water rights holders to sell or lease water to other users—within some constraints.

East Fork Irrigation District withdrawal

So the West got a byzantine water rights management system —incredibly inefficient and, some say, shot through with illogic and inequities. In Washington and Oregon, water belongs to the public, and the states grant usage rights. The State of Oregon requires irrigation districts to meter water use. So far, so good.

But both northwest states countered this enlightened practice by the prior appropriation rule, under which the person who first uses the water gets first access if there’s a shortage. Junior users may be out of luck, unless: in severe drought a governor steps in to keep urban dwellers and livestock alive. Prior appropriation was adopted during the west’s mining era, when desperately competitive prospectors staked claims right and left and needed water to sluice gold or silver.

A SECOND OLD RULE IS ‘USE IT OR LOSE IT.’ This means that if you have rights to a certain amount of water every year but you don’t remove that water from the flow, somebody else can use it. If you don’t use all the water you’re entitled to, you will eventually (usually in about five years) lose the right to the amount you are not using. This is an obvious recipe for waste.

Irrigation Circles in Eastern Oregon adjacent to the Columbia River.

THE THIRD TRADITIONAL RULE: Water must go for ‘beneficial uses.’ Historically, these have been agriculture, agriculture, agriculture, industry, mining, municipalities, and, more recently, power generation. Agriculture, you may have noticed, is by far the preferred use. What if you want to leave the water in the stream for the benefit of the fish, the frogs, the water skippers, your own esthetic satisfaction and so on? That’s not so high up on the totem pole.

Historically, the only beneficial use for leaving water in-stream was to keep the stream navigable.

Defining beneficial use to include leaving water in its bed may be the rule that has changed the most. In the Pacific Northwest, protecting fish is required by law and is seen by more and more citizens as a positive value. For the legal muscle to help do this, we owe a lot to the Native American tribes, which represent a kind of wild card in the system. As sovereign nations, they stand between the federal government and the states in the legal pecking order. Northwest tribes have treaty fishing rights with the feds that make keeping water in rivers and streams a necessity.

In fact, there’s a big difference between the Northwest and the Southwest in this respect, says Douglas Kenney, director of the Western Water Policy Program at the University of Colorado Law School in Boulder. Southwest Native Americans have no such fishing rights in their treaties, so their ability to argue that not taking the water out constitutes a beneficial use is much weakened, he says.

BECAUSE TRIBES ALSO HAVE THE OLDEST CLAIM to prior appropriation, their water rights technically precede the states’ ability to regulate water usage, and they shouldn’t have to prove beneficial use to retain their rights, either, writes Robert Anderson, director of the Native American Law Center at the University of Washington School of Law. But, says Kenney, tribes are highly restricted in how they can use their water. They can’t sell it across state lines, for example, and they can’t use its value as collateral for building reservation infrastructure.

Further, he adds, “If they’re not currently using that water, somewhere on the system there is a current user that fears their supply is going to go away.” Thus there are built-in costs and benefits that may be illogical or even technically illegal, but have been standard practice for so long that they would be very difficult to dislodge.

Nobody thinks there’s any chance that we’ll ever circle back to Powell’s watershed organizational scheme. No, it’s capitalist economics that appears to be the favored solution, says Kenney. “The obvious way to deal with the problems of shortages and water being allocated in ways that might not suit modern needs,” he says, “is to reallocate through market mechanisms.” In some parts of the West, farmers are already selling most of their water to municipalities.

Many tribes would like to share in this opportunity, says Jeanette Wolfley, a Shoshone-Bannock tribal member and assistant professor at the University of New Mexico School of Law in Albuquerque. Wolfley says states want tribes to use their water on reservations instead. Tribes usually don’t have the infrastructure or the interest in using all their water rights that way, and they could use the money.

Many tribes would like to share in this opportunity, says Jeanette Wolfley, a Shoshone-Bannock tribal member and assistant professor at the University of New Mexico School of Law in Albuquerque. Wolfley says states want tribes to use their water on reservations instead. Tribes usually don’t have the infrastructure or the interest in using all their water rights that way, and they could use the money.

Another way tribes could be helpful, Wolfley says, would be to save up water banks that could be tapped in times of shortage for uses like irrigation. But, she adds, “When the feds and state policymakers are considering water use, tribes aren’t at the table. If tribes were at the table, junior water users, meaning oftentimes states and irrigators and others, would have more certainty.”

WHATEVER HAPPENS, THE GORGE’S FATE will depend on that of the vast Columbia River Basin, which is governed by two countries, seven states, hundreds of smaller governmental and advisory entities, 13 Indian tribes, and eight federal agencies with water-related responsibilities. Getting all stakeholders to feel they’ve been fairly treated will be a massive undertaking, and some of the old water rights structures may have to be dissolved.

For example, the priority system doesn’t guarantee that everybody will get a proportional amount of what water there is, and a market system means only those who can afford it will get water. But, Kenney says, the Pacific Northwest is known for being creative in managing land management resources and achieving the spirit of what Powell talked about without literally implementing it. We can only hope when the going gets especially tough that spirit prevails.

Paid Advertisement:

Interested in reading more about Gorge water issues?

Irrigating our Future in the Midst of Climate Change

Columbia River Dams and Salmon

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]