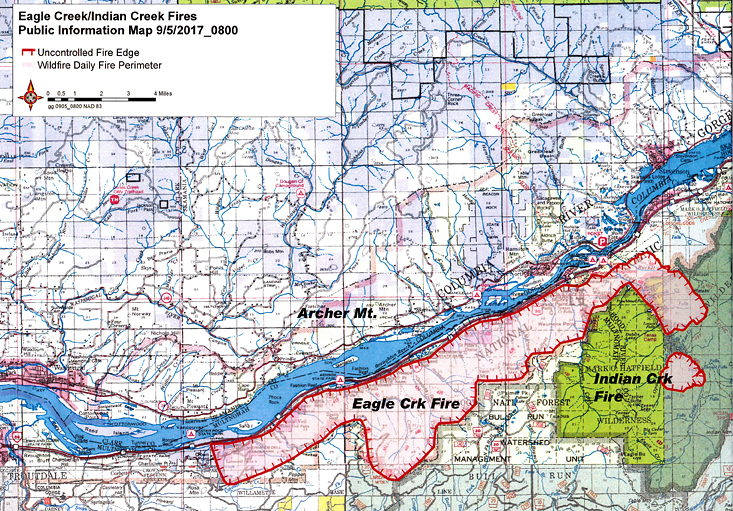

Eagle Creek Fire Tues. 9-5-2017

Eagle Creek Fire. 12 noon. 9-5-2017 Tom Berglund, Public Information Officer for the fire reported this morning, “The fire blew up last night to over 10,000 acres pushing the fire west to Corbett. The town of Corbett is requesting help. Ember started a fire on Archer Mountain in Washington. The focus of efforts is on protecting lives and structures.” For more: https://inciweb.nwcg.gov/incident/5584/

Evacuations area have been expanded.

I-84 is now closed westbound from The Dalles at MP 87 (near bridge). It remains closed east and west bound from Hood River MP62 to Troutdale. For more info: odot.com or wsdot.com