You Are Needed

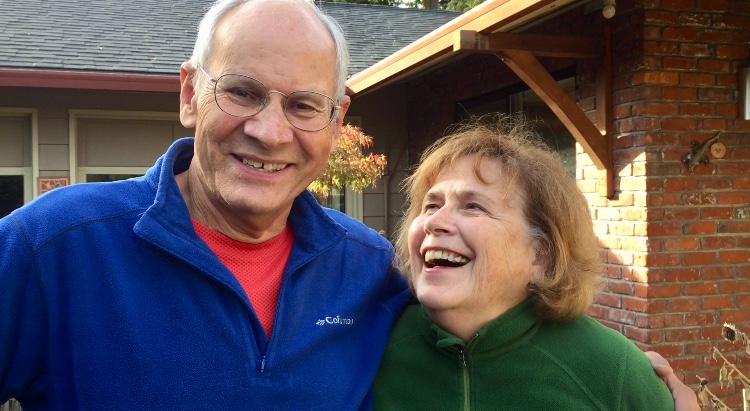

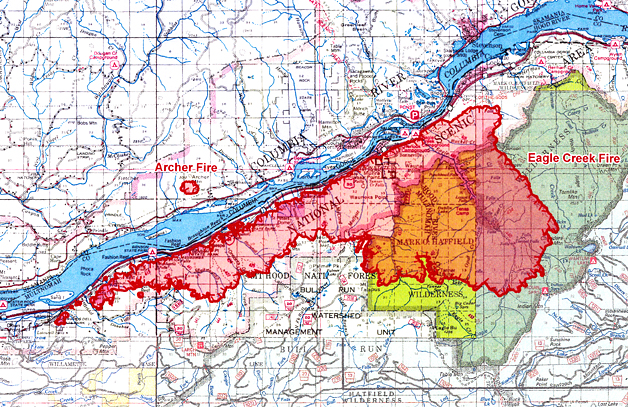

Ten years ago, Susan Hess had a vision of channeling her passion and fervor for protecting the waters, lands, plants and wildlife of our beloved Columbia River Gorge into an initiative that would educate and inspire locals to join her in being the change our Gorge needed. In partnership with her husband Jurgen and a team of like-minded citizens, she invested her private funds, energy and heart into creating what has evolved into EnviroGorge, LLC, the primary resource for in-depth investigative reporting and environmental stories throughout the Gorge and beyond.

Today, more than ever, this initiative is needed to protect this extraordinary region. People doing high integrity, quality work for EnviroGorge is essential. While many donate their time, money is also required. Susan and Jurgen will continue to fund and spearhead EnviroGorge, but help is needed to expand our outreach and take us to the next level.

We ask you to join us in supporting EnviroGorge, LLC with a financial gift. No amount is too small.

We never know when one financial contribution or seemingly modest conscious act might help change the course of history, or engage someone else who will play a key role. Susan and Jurgen embody this concept of being the change and igniting others to do the same– trusting that people will make more conscious environmental decisions once they have a clearer understanding of the issues. This core philosophy is what inspires the work we do.

Please mail your check to: EnviroGorge, LLC, PO Box 163, Hood River, OR 97031 or via Paypal on EnviroGorge

In Sincere Gratitude,

The EnviroGorge Volunteer Advisory Council: Tina Gallion, Eileen Garvin, Heidi Logosz, Buck Parker, Tom Post, Lynda Sacamano, Jessica Walz Schafer and Stu Watson

Potential Funding Levels:

$20-50 Continue our work

$60-120 Youth outreach and engagement

$125-350 Hire skilled freelance writers

$375-$1000 Sponsor our site