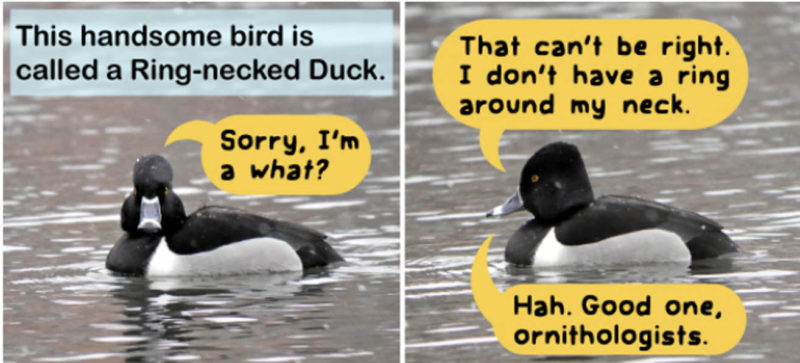

Just for Fun!

Ring-necked ducks are commonly spotted in flocks in the Columbia River and Gorge lakes during fall/winter. Learn more about identifying this bird at the Cornell Lab of Ornithology website. This cartoon was published with permission of Bird and Moon.com

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]

[/media-credit]