Idaho’s Clearwater River Basin added to ‘most endangered’ list

American Rivers sounds the alarm as a new management plan opens the area to logging, dredge mining and dams

Wild decisions: A tributary of the Snake River, the South Fork Clearwater River runs for 62 miles through north-central Idaho. A new federal plan might imperil its health. Photo: Lisa Ronald

By Kendra Chamberlain, April 28, 2025. The Clearwater River Basin, dubbed a Noah’s Ark for chinook salmon, steelhead and native trout by the conservation group American Rivers, has been added to group’s annual list if Most Endangered Rivers.

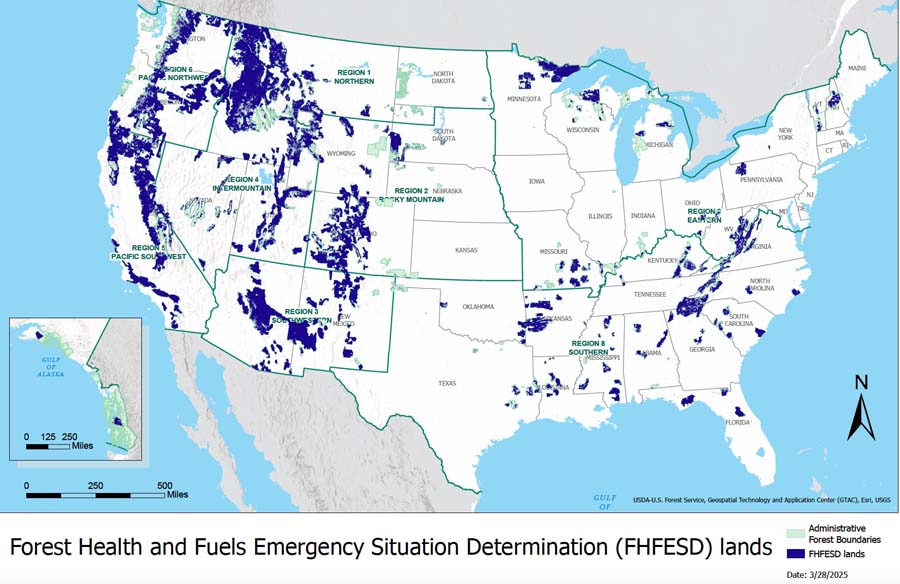

The move comes after a controversial U.S. Forest Service land management plan stripped protections for 700 miles of river corridors in north-central Idaho’s Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest.

Nearly 10 years in the making, the forest plan took a surprise turn in 2024 when the Forest Service released a suitability analysis that removed interim protections from 17 rivers in the Clearwater River Basin.

The new plan, finalized in January, makes the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest the only forest in the Pacific Northwest in the last decade to see a decrease in river protections under a new management plan, as reported by Columbia Insight. The plan also includes a four-fold increase in logging in the national forest, and opens up previously protected areas for dredge mining and dam building.

The basin is home to the Lochsa, Selway and Middle Fork Clearwater rivers, each designated as Wild and Scenic and permanently protected. But the headwaters of the Lochsa, as well as the North and South Forks of the Clearwater River—all of which were deemed eligible for Wild and Scenic designation in the 1980s—lost its interim protections under the new forest management plan, before the permanent designation process could be completed.

River corridors identified as eligible for Wild and Scenic status are afforded interim protections until a designation is made official by either Congress or the Secretary of the Interior. That process can sometimes take decades. But taking river corridors off the eligibility list isn’t a standard practice in land management plan updates.

Conservationist groups like American Rivers are ringing alarm bells.

“Before this [Trump] administration, the Nez Perce-Clearwater National Forest was the exception, not the rule,” Lisa Ronald, American Rivers’ associate conservation director for western Montana, told Columbia Insight, referring to the loss of protections.

With the Trump administration’s directive to increase logging and other extractive industries across national forests, Ronald said there’s a real danger that this could set a new norm for forest plan updates.

Idaho Rivers United has also been raising awareness about the issue.

Nick Kunath, Idaho Rivers United conservation manager, said the Forest Service’s decision to remove protections while also increasing logging and other extractive activities will likely have huge implications for the entire Clearwater River Basin, and may imperil the health of the three rivers that are currently being protected.

“The reduction in protections to Wild and Scenic Rivers, it really [is] a new precedent, something that has national implications,” Kunath told Columbia Insight. “The combination of loss of protections and dramatically increasing the amount of areas that have previously been restricted, as well as just the volume that they intend to log, those things often lead to degraded water quality, [degraded] habitat conditions and a lot of the things that these protections that were lost were aimed to prevent from happening.”

The Clearwater River Basin is particularly important to fish seeking cold water.

“These are the rivers that are going to provide the coldest water 20, 30 years from now,” said Ronald.