This new innovation could make solar farms more wildlife friendly

In southern Oregon, the massive Diamond Solar Project will be part of a trending design and construction style

Heating up: Chicago-based Invenergy helped build the Luning Solar Energy Project in Mineral County, Nev. Its latest project will be located in Oregon not far from Crater Lake. Photo: Invenergy

By Kendra Chamberlain. November 26, 2025. You’re an elk. You’re on your annual migration from the mountains to lower-elevation feeding grounds, the same route traveled by countless generations of your ancestors.

An obstacle blocks your path. You’ve encountered nothing like it before. A high, metal fence. Behind the fence, massive, sharp angled panels reflect sunlight with intensity foreign to your concept of the world.

What now?

Solar energy is great. But it comes with costs. One of these is impact on wildlife.

Habitat connectivity has emerged as an environmental concern related to renewable energy facilities like large solar farms.

Utility-scale projects degrade habitat and typically include six- to eight-foot-high fencing, which severs migration corridors and bars wildlife access to habitat and resources.

“Solar facilities impact fauna through habitat loss and fragmentation, altered microclimate and creation of novel habitat,” according to a 2025 report published in the journal ScienceDirect. “The rapid transformation of landscapes necessitates urgent research into biodiversity impacts of solar facilities worldwide.”

Some developers are getting the message.

Tianqiao Chen. Photo: Shanda Group

At a proposed solar installation in southern Oregon, the renewable energy company Invenergy has plans to build a wildlife corridor and a nearly 2,000-acre conservation area to help offset the ecological impacts of industrial-scale construction in a largely undeveloped wilderness.

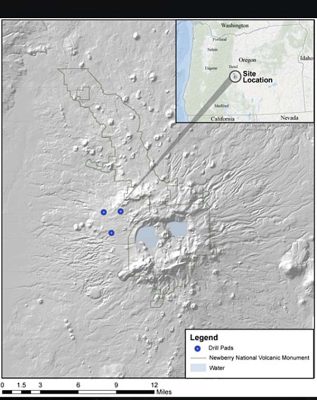

Chicago-based Invenergy is the global renewable energy company behind the Diamond Solar Project, a proposed 200-megawatt facility located near the junction of U.S. Route 97 and Oregon Route 138, nicknamed the “Highway of Waterfalls.” The location is just east of Diamond Lake in the Umpqua National Forest and northeast of Crater Lake National Park.

The project passed a milestone in October when the Klamath County Planning Commission approved permits to install 406,000 solar panels and on-site battery storage on a 1,560-acre plot of forested land.

The land is owned by the private investment firm Shanda Group. Founded by Chinese billionaire Tianqiao Chen and other family members, Shanda Group is the second largest foreign owner of land in the United States.

Chen owns nearly 200,000 acres of forestland in Oregon’s Klamath and Deschutes counties.

Wildlife and solar mitigation

The Diamond Lake project site is home to wildlife including deer and elk. It includes access to important water resources, according to the Oregon Department of Fish and Wildlife.

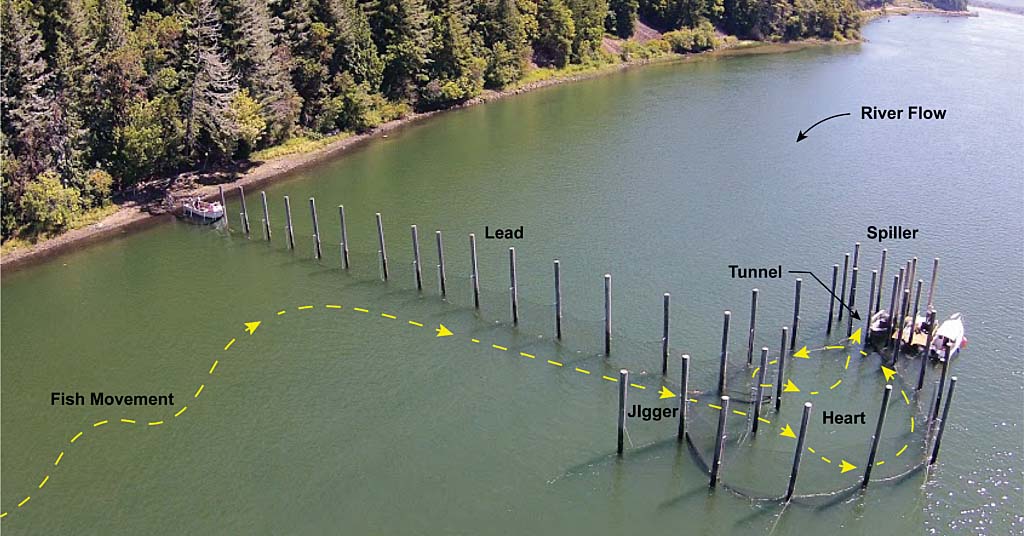

“We were concerned about an impediment to migration, as well as blocking off a water source,” ODFW’s Jeremy Thompson told Columbia Insight. Thompson served as the department’s energy coordinator while the Diamond Solar proposal was created. “There are some water sources through that corridor that showed use by ungulates, both deer and elk in that area.”

ODFW offers energy siting guidance to help inform designers of large developments on ways they can minimize or mitigate impacts to local habitat and wildlife.

Hot spot: The red rectangle represents the approximate location of the Diamond Star Project solar installation near the intersection of state and federal highways. The large blue circle in the lower left is Carter Lake. Photo: Google Earth

In the case of the Diamond Solar proposal, Thompson said ODFW staff asked Invenergy to include a wildlife corridor that runs through the facility to offer a way for ungulates to move through the land.

The company and ODFW settled on a 600-foot-wide wildlife corridor.

Thompson said the inclusion of wildlife passages in solar build-outs is becoming common, though it’s still a relatively new concept.

“We’ve worked with multiple companies to try to institute passage through solar farms, especially as we talk about some of the larger solar farms that are being proposed in north-central Oregon,” said Thompson. “We just haven’t seen one that’s been constructed yet.”

ODFW hopes to conduct research using collared deer and game cameras to determine if the corridor is successful.

“The science isn’t sound yet on how wide that corridor needs to be for animals to feel comfortable using it,” said Thompson.

Renewable energy projects across the country have begun attempting to accommodate wildlife in their designs, in hopes of reducing environmental harm.

Design tweaks include fencing with holes large enough to allow small animals to slip through, and passages or corridors for larger animals.

Early evidence suggests these features can be successful.

The Nature Conservancy, for example, tracked a variety of small animals slipping through wildlife-friendly fencing at a solar facility in North Carolina.

The Diamond Solar Project also includes a 1,900-acre conservation area, which is meant to replace habitat lost to the solar facility. That land is also owned by Shanda Group.

Construction of the Diamond Solar Project is expected to take two years. Invenergy plans to have the facility finished by 2029.