Court orders emergency measures to protect salmon, steelhead

A challenge to federal withdrawal from cooperative deal, the decision affects Columbia and Snake River dams

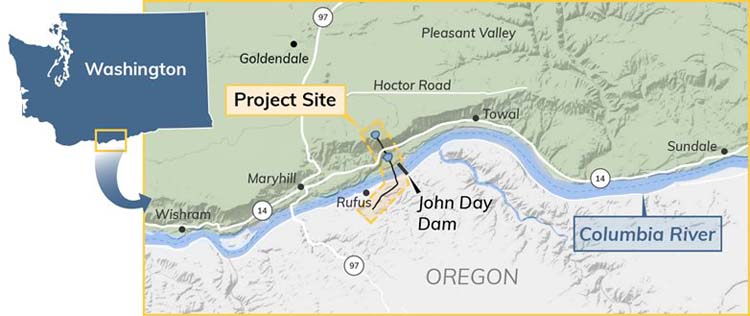

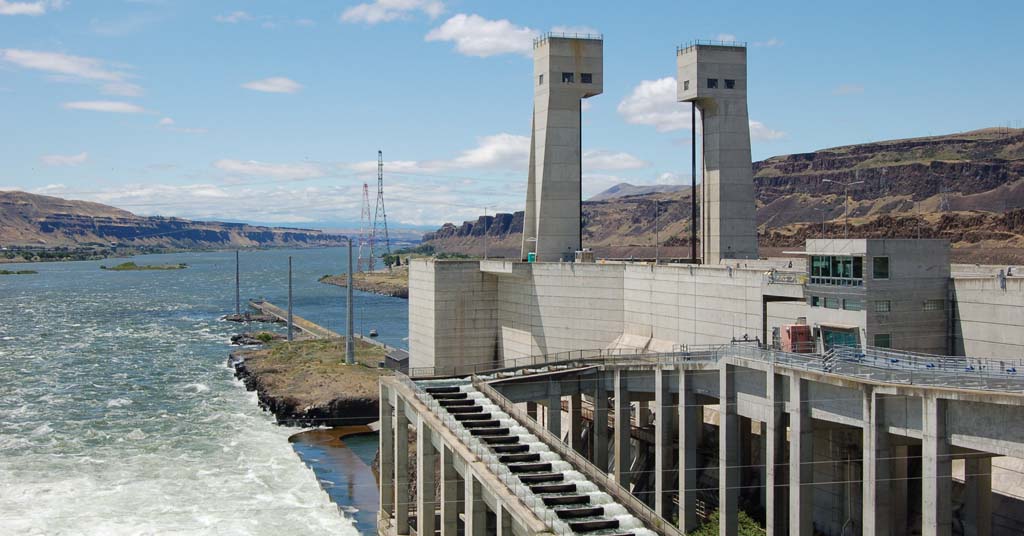

Spillage: The amount of water that spills over dams, such as the John Day Dam on the Columbia River, is a crucial piece of salmon recovery. Photo: USACE

By Kendra Chamberlain. February 27, 2026. Salmon of the Columbia River Basin don’t know it, but the species was handed an important legal victory in an Oregon district court this week. On Feb. 25, U.S. District Judge Michael Simon ordered a series of emergency operations at eight dams on the lower Columbia and Snake Rivers to aid in fish passage.

The decision followed a request for a preliminary injunction filed by environmental law firm Earthjustice on behalf of a group of salmon advocates.

Effective March 1, federal dam operators must increase spill levels and hold reservoir levels lower, in hopes of giving migrating fish the best chance to navigate the deadly Columbia River Basin dam system.

The measures themselves aren’t new, but a continuation of earlier dam operations that were put in place to protect salmon. As such, Simon wrote in his decision that the federal government’s arguments against the measures were unconvincing.

“The majority of the spill has been implemented over the years without such negative repercussions, and the Court does not anticipate such calamities will ensue from the current spill order,” Simon wrote.

The decision is the latest chapter in a 30-year legal battle between federal agencies and a coalition of Pacific Northwest Tribes, states, conservation and fishing groups working to keep Pacific Northwest salmon from going extinct. The court’s decision is a vital win for this season’s salmon, according to Jacqueline Koch, communications manager at the National Wildlife Federation, one of the groups represented by Earthjustice.

“Now we’ve got these emergency measures in place to help salmon get through the next season. Most of these measures will be implemented March 1,” Koch told Columbia Insight. “It’s super important that this goes into place—because the fish are swimming toward extinction.”

Move counters Trump order

The case is far from over. Its litigation has spanned six presidential administrations. It has seen nearly every biological opinion on the Columbia and Snake River dams issued by the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration, the federal agency charged with conserving and managing coastal and marine resources, overturned by the courts.

The tide seemed to turn in 2021, when Earthjustice, the Nez Perce Tribe, the state of Oregon and the Biden administration sought to pause the ongoing legal fight in hopes of reaching an agreement out of court. It worked. In 2023, a group of four Tribes, two states and the federal government announced the Columbia Basin Restoration Initiative (CBRI).

The Biden administration pledged $1 billion over a decade to help restore salmon and fund tribal clean energy projects.

“I’ll have the fish.” Photo:Creative Commons

The agreement was hailed as an important step in addressing a century’s worth of environmental degradation in the name of energy development. Some went so far as to dub Biden “the salmon president.”

Two years later, the rug was pulled from beneath the agreement’s signatories. At the direction of the Trump administration, the federal government unilaterally killed the agreement by pulling out.

The deal was opposed by Republicans who called it “radical environmentalism” and said it would jeopardize the region’s power supply, irrigation and ability to export grain to Asia, according to The Associated Press.

“We had no option but to resume our longstanding litigation to protect endangered salmon,” said Earthjustice attorney Amanda Goodin in a statement in October 2024, when the firm filed its request for a preliminary injunction.

With the parties back in court, it’s unclear if there’s hope of reviving the CBRI. Many dam proponents cheered the Trump administration’s decision to kill the deal. But Simon pointed out in his decision that the courts have historically sided with salmon in this case.

“This case has a long history of failed [biological opinions], court intervention and monitoring, and federal defendants’ attempts to ‘manipulate’ variables and engage in ‘sleight of hand’ conduct to avoid making hard decisions and face the consequences of its actions,” Simon wrote. “It appears that the 2020 [biological opinion] and 2020 [final environmental impact study] follow this disappointing history of government avoidance and manipulation instead of sincere efforts at solving the problem and genuinely remediating the harm.”

The Department of Justice declined to comment on the order.

Salmon advocates say they’re committed to continuing the legal battle on behalf of salmon, as fish returns remain historically low.

“National Wildlife Federation has been fighting to protect salmon runs in the Columbia River Basin for more than 30 years. And we’re not going to give up now,” said Koch. “The salmon are swimming toward extinction. They are at the heart of our Northwest way of life. And so we’ll continue to move forward on this as needed.”