Opinion: Why the Gorge pumped-hydro project is opposed by the Yakama Nation

Though not opposed to alternative energy sources, tribes have borne disproportionate impacts of green energy development

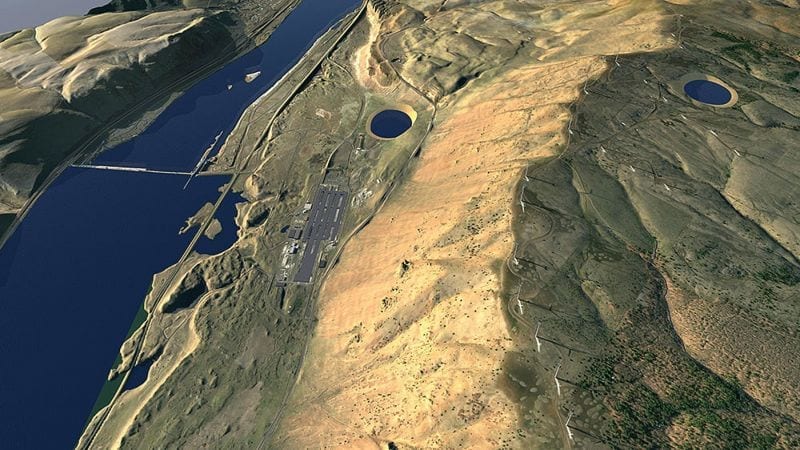

Picture power: This rendering shows the position of reservoirs for the proposed pumped-hydro energy project relative to the Columbia River, John Day Dam, site of the former Columbia Gorge Aluminum smelter and ridgeline wind turbines. Image from Washington Department of Ecology

By Elaine Harvey and Jordan Rane. April 15, 2021. It’s been called one of the most monumental treaties and land grabs of its kind in U.S. history.

The 1855 Walla Walla Council, would bring five sovereign tribal nations of the Great Columbia Plateau to the Washington Valley, ceding millions of acres of Native land to the U.S. government.

In return, three separate Native American reservations would be established, including a 1,130,000-acre parcel in southern Washington granted to the Yakama Nation. The federal treaty would also provide rights for Yakamas to exercise “in common with” citizens of the United States at all “usual and accustomed” places within the treaty territory. This would become the supreme Law of the Land under the U.S. Constitution.

A Kah-milt-pa chief was one of the signatories of this 1855 agreement. In the Rock Creek Sub-basin and adjacent areas of Klickitat County, the treaty would serve to protect the homeland of the Kah-milt-pa Band of the Yakama Nation.

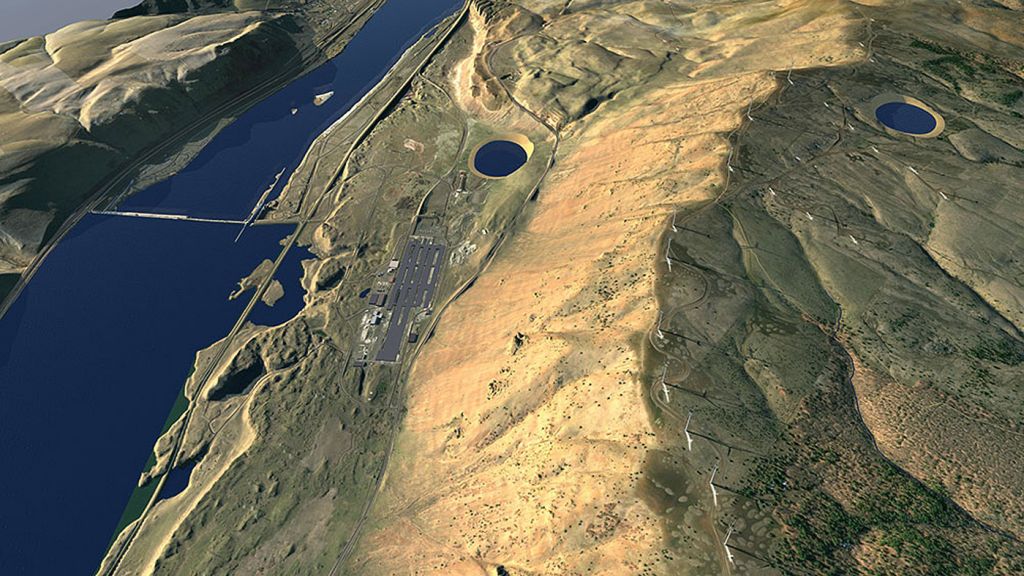

Valued land: The proposed site for the pumped-storage project—seen here from Oregon looking across the Columbia River—would impact cultural and traditional Yakama activity. The upper reservoir would be located just behind the highest point on the ridge. Photo by Jurgen Hess

Cut to over 150 years later, in a Columbia Basin landscape now streaked with dams, wind turbines and the toxic remnants of a shuttered aluminum smelter, a Kah-milt-pa signatory from that world-altering era would simply not recognize his own home.

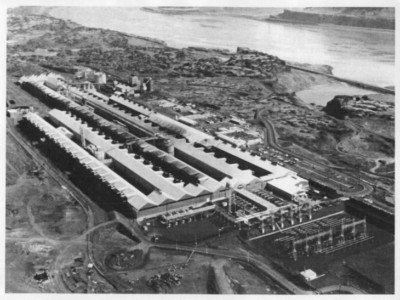

The latest proposed development here—a massive, $2 billion pumped storage hydroelectric project located 20 miles south of Goldendale, Washington, on the banks of the Columbia River near the John Day Dam—threatens to slash deeper still into a historic agreement that has not lived up to its repeatedly marginalized promises.

Sacred site

The Yakama Nation, which has felt the encumbrances of green energy projects since the first dam was constructed on the N’chi Wana (Columbia River) over 80 years ago, has opposed the Goldendale Energy Storage Project from the start.

Situated directly on a sacred tribal site, the project directly impacts Yakama Nation cultural, archeological, ceremonial, monumental, burial petroglyph and ancestral use sites.

The pumped-hydro storage venture is spearheaded by Portland-based hydropower developer Rye Development and backed by Copenhagen Infrastructure Partners (CIP), a Danish investment firm specializing in green and renewable energy projects. The two companies have teamed up on a smaller pumped-storage system in Klamath County, Oregon—Swan Lake Energy Storage—that has recently secured a 50-year license from the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission (FERC).

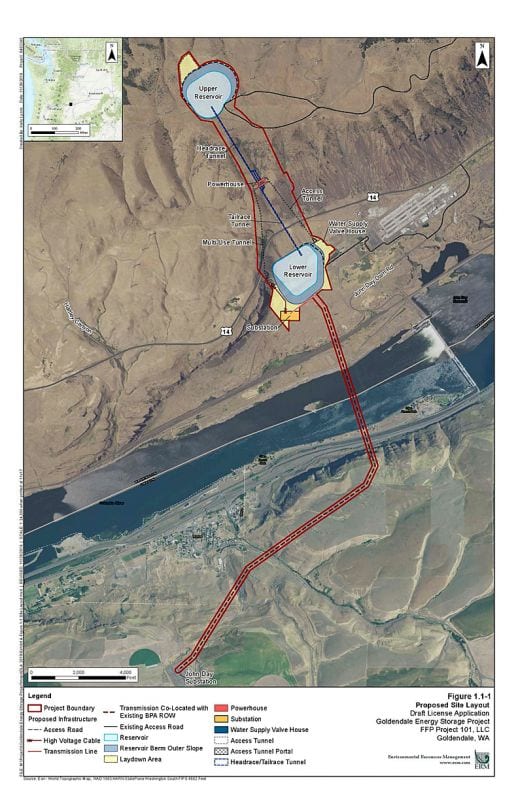

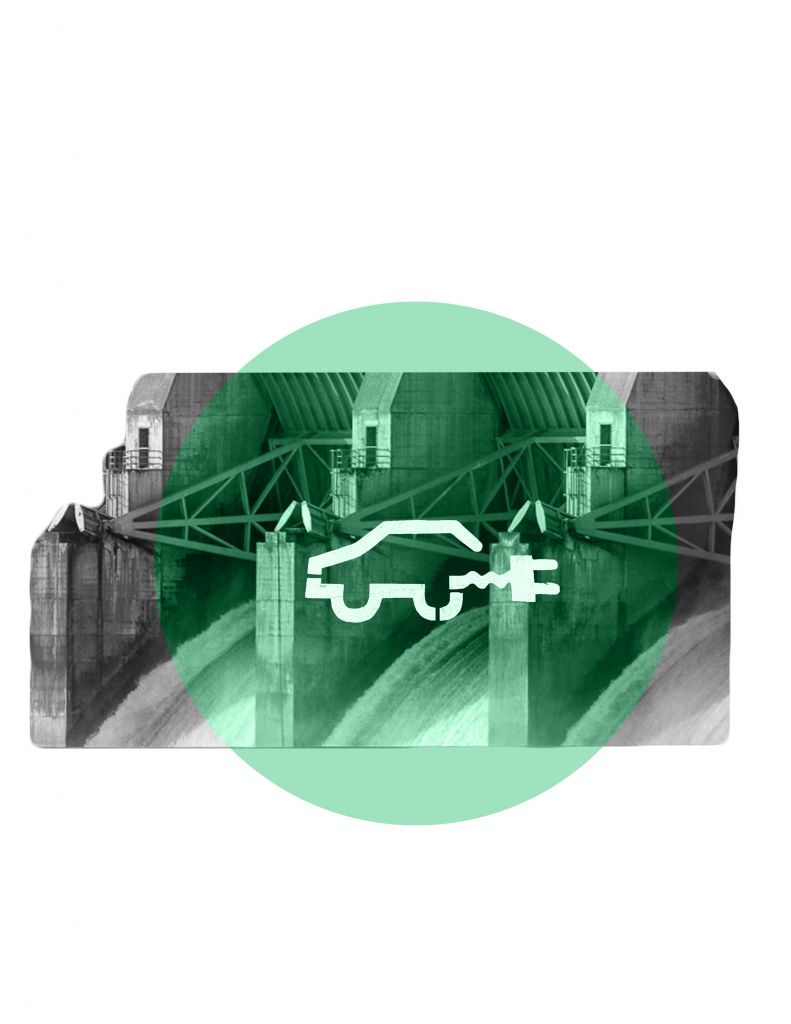

The much larger Goldendale proposal, which requires the creation of two reservoirs with underground water conveyance tunnels and electrical transmission lines, aims to be the largest hydroelectric project of its kind in the Northwest—with a proposed operation date set for 2028 if licensing is granted by FERC and the Washington Department of Ecology. Ecology has completed its scoping hearings for the project and is currently preparing a contract to begin work on an environmental impact statement.

MORE: Danish firm acquires pumped-hydro energy projects in Washington and Oregon

Although located on private land, the proposed site is also situated on Put-a-Lish—a sacred site to the Yakama. A place where there is an abundance of their traditional foods and medicines.

The Area of Potential Effect (APE) will also directly impact Native American Traditional Cultural Properties, historic and archaeological resources, and access to exercise ceremonial practices and treaty rights.

The project site falls directly upon the ancestral village site of the Willa-witz-pum Band and the Yakama fishing site called As’num, where Yakama tribal fishermen continue to practice their fishing treaty rights.

Additional cultural resources will be affected as well, such as petroglyphs and other traditional cultural properties.

How it works

You’d never know any of these issues existed if you listened only to the project’s sunny forecasts from Rye Development.

“We believe this project will be one of the cornerstones of Washington’s and the broader Pacific Northwest’s energy economy,” said Erik Steimle, Rye’s vice president of project development, during a recent Hood River County Webex presentation that was largely met with effusive praise and excitement by a small online group of staff and community attendees.

“The project once-constructed will create 1,200 megawatts of renewable electricity on demand—from two ponds,” added Steimle.

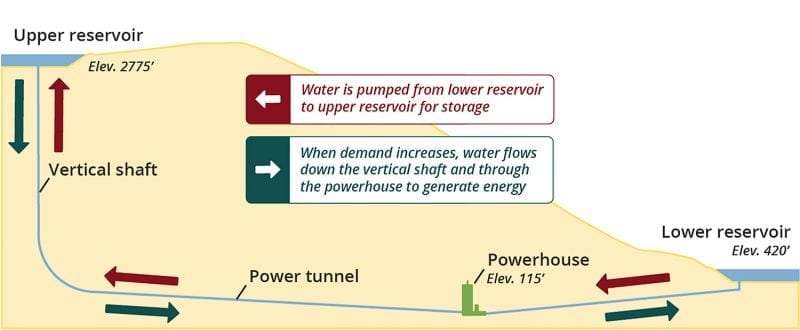

Pushing power: Transferring water between upper and lower reservoirs generates power. The project would need 360 acre-feet of water each year to replenish water lost through evaporation. Image from Washington Department of Ecology

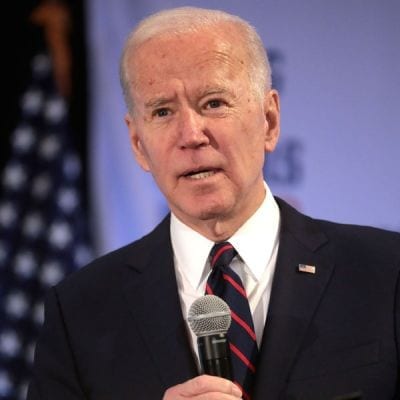

The “ponds” are 61- and 63-acre reservoirs—an upper and lower reservoir with a 2,400-foot elevation differential—in the Columbia Gorge’s Bi-State Renewable Energy Zone. The “closed-loop” system would utilize a substantial amount of start-up water from the Columbia River in the amount of 7,640 acre-feet to fill up one of these receptacles—not including future Columbia re-tappings for evaporation loss, leakage and incidentals. (Given that water would be transferred between the two reservoirs as needed, only one reservoir would be filled at a time. —Ed.)

During peak demand times on the energy grid, water would be released from the upper reservoir through turbines to the lower reservoir to generate electricity. It would then be pumped back to the upper reservoir during lower (cheaper) demand periods and stored for future use—in a cyclic system Steimle touts as the “oldest form of storing energy and one that is widely recognized as the cheapest.”

“I would suggest that the opposition to this project—and there is some—is quite low,” Steimle replied during the Webex presentation, when eventually asked about any objections to the development.

MORE: Environmental justice at Hanford: Reconnecting Indigenous people to their land

When further asked about specific elements of Yakama opposition, not one of the Yakama Nation’s long-raised objections (including those voiced in this article) were mentioned.

“This is a traditional landscape for the Yakama Nation and they have concerns about additional development on this private land,” said Steimle, emphasizing that the company has consulted and been in conversation with the tribal council since the outset of the project, and has also worked with a Yakama cultural resources team at the tribe’s request to target areas that could be impacted. “One of the benefits of developing a project like this is that it is regulated by the FERC. Their timeline is long, and we have the patience to continue to have that conversation.”

Meanwhile, the Yakama Nation has submitted comments to federal agencies to oppose the project in order to protect the Yakama sacred site Put-a-Lish, cultural resources, water resources, a fishing access site, an ancestral village and wildlife habitat.

Coalition supports Yakama Nation

Wildlife biologists and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service have repeatedly voiced their own concerns that the two planned reservoirs will attract more birds to a spot already rife with wind-turbine bird kills.

“This history of mortalities shows a landscape already compromised by wind power infrastructure,” the USFWS has commented, regarding golden eagle deaths in an immediate area that is also home to bald eagle and prairie falcon nesting grounds. “The potential of the proposed Project to further alter the remaining laminar wind currents lends credence that resulting impacts to avian species would not be exclusive to wind power production in the area.”

Connecting to the grid: The project would include a 3.13-mile-long, 500-kV transmission line routed from a substation south across the Columbia River connecting to the Bonneville Power Administration’s existing John Day Substation. Image from Washington Department of Ecology

In repeated comments, the USFWS has also expressed uncertainties about the developer’s announced plans to mitigate habitat loss as opposed to merely minimizing it.

In solidarity with the Yakama Nation, over a dozen environmental organizations including Columbia Riverkeeper, The Sierra Club and the Audubon Society have issued a joint letter to Oregon and Washington governors and senators in their objection to the Goldendale Pump Storage Project.

“We don’t oppose pumped storage projects generally, but we do think that green energy that is going to obliterate tribal, cultural and religious resources is not OK. Nor is fast-tracking green energy on the backs of tribal nations,” says Columbia Riverkeeper staff attorney Simone Anter. “Looking at this area, these tribes have really borne disproportionate impacts of green energy development. We’ve seen the Yakama Nation lose access and be forced to work out different access agreements because of the wind turbines. We’ve seen traditional villages flooded by the John Day Dam. We’ve seen that up and down the Columbia.

“Rye Development has done a great job of muddling public opinion on Yakama Nation’s position. Especially when you’re looking at a site where the tribal opposition to development is so clear.”

MORE: Under Pressure: The Oregon community desperate for water

The N’chi Wana has always been home to many tribes and bands of the Yakama Nation, which has felt the encumbrances of green energy projects since the first dam of many to follow was constructed on this great river.

Celilo Falls was the most revered tribal fishing grounds to be desecrated on the Columbia, lost to dam construction.

Fifty years later, wind farms came to the region and once again impacted Yakama cultural properties.

Today an enormous water pumped-storage development is proposed on Yakama “usual and accustomed” treaty lands—where Kah-milt-pa continue to practice their traditional ceremonies at the Rock Creek longhouse in the lower sub-basin, and make their seasonal rounds throughout their usual and accustomed lands to gather their traditional foods.

Its impact would be irreversible and one more significant desecration to Yakama resources.

The views expressed in this article belong solely to its author and do not reflect the opinions of anyone else associated with Columbia Insight.

Elaine Harvey is from the Kah-milt-pa Band of the Yakama Nation and is a lifelong resident of Goldendale, Washington. She has been a fish biologist for the Yakama Nation Fisheries Program for the past 15 years with an M.S. in Resource Management and a B.S. in Fisheries and Aquatic Sciences. Elaine dedicates her career to conserving the traditional foods and lands so sacred to her people and sharing that knowledge with the younger generations.

Jordan Rane is an award-winning outdoor writer whose work has appeared in CNN.com, Outside, Men’s Journal and the Los Angeles Times.

READ MORE INDIGENOUS ISSUES STORIES.

The Collins Foundation is a supporter of Columbia Insight’s Indigenous Issues series.

Columbia Insight‘s series focusing on the aluminum industry in the Columbia River Gorge is supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Columbia Insight‘s series focusing on the aluminum industry in the Columbia River Gorge is supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.