Waste Land: Where the aluminum bodies are buried in the Columbia Gorge

Although the region’s big aluminum producing days are long past, the waste the industry left behind hasn’t gone far

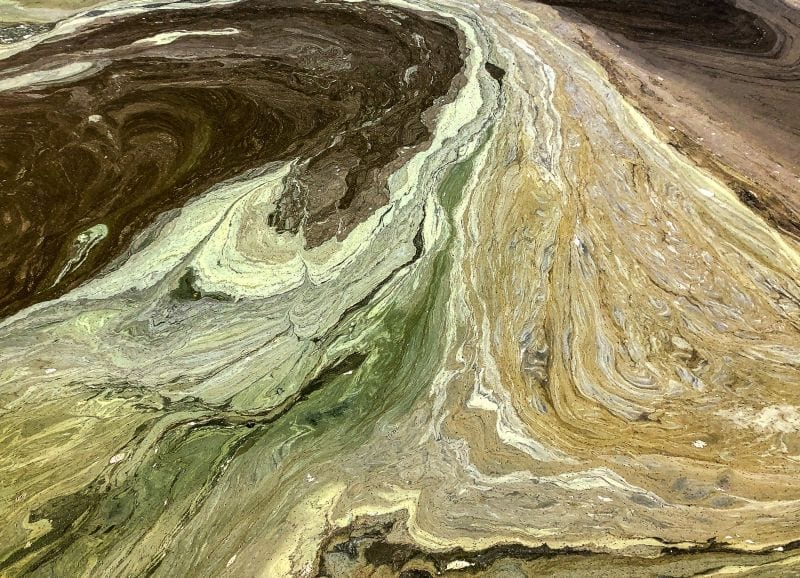

Buried legacy: From 2007-2010, the Wash. Dept. of Ecology and U.S. EPA removed over 135,000 tons of waste from the RAMCO aluminum site. The Port of Klickitat filled the excavation site. The site was removed from the Hazardous Sites List in 2016. Photo by Wash. Dept. of Ecology

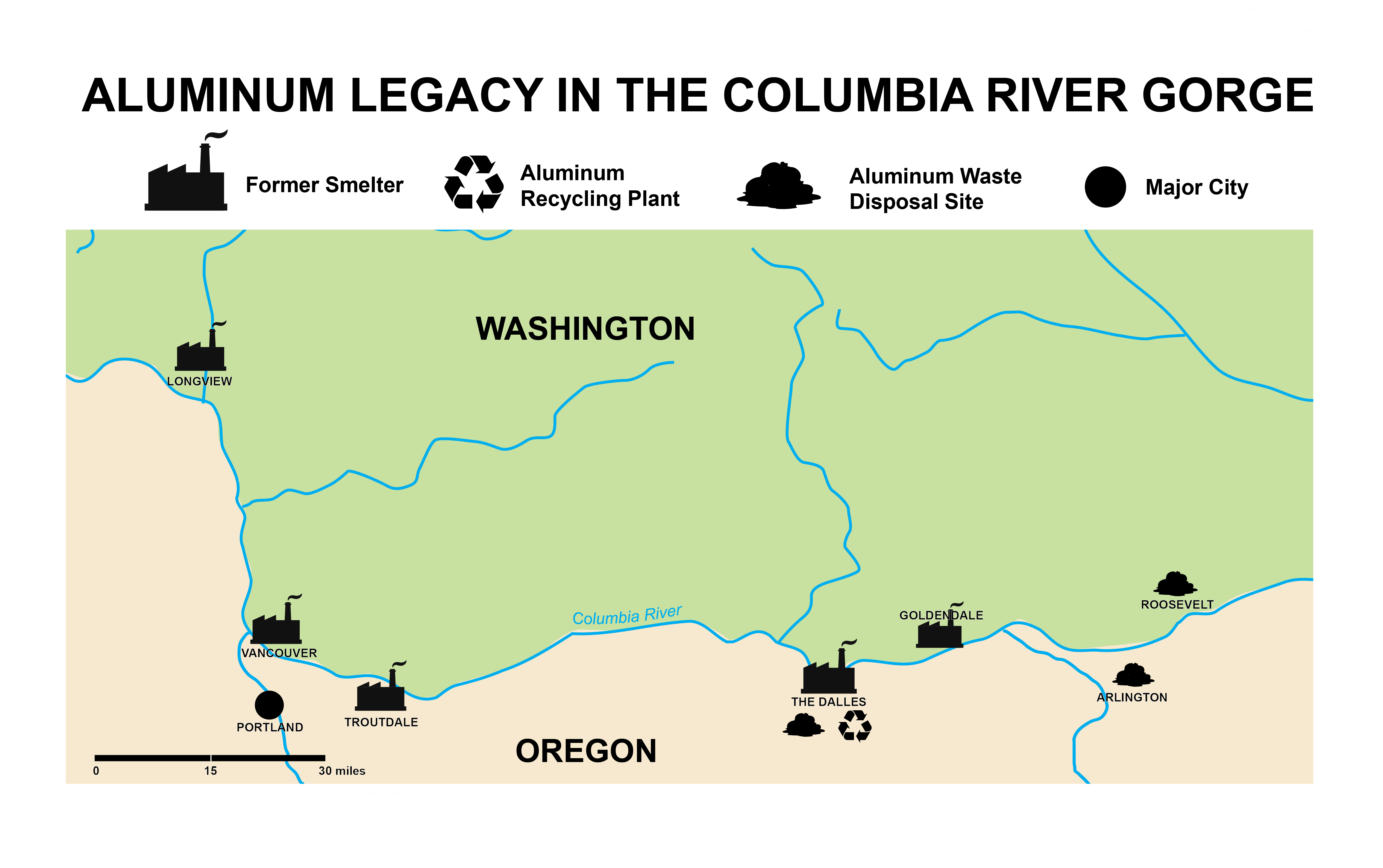

By Valerie Brown. June 10, 2021. In the Columbia River Gorge thousands of tons of aluminum waste is stored in municipal solid waste landfills not intended for this purpose. The waste comes from numerous, long-closed smelters on both sides of the river that were once mainstays of the region’s economy.

But the waste isn’t simply a static relic of a bygone time. Even when stored underground, aluminum waste poses public risks, principally from unwanted chemical reactions, fires and explosions. In the Columbia River Gorge, these may increase when the aluminum recycling industry returns to full post-pandemic activity.

4-PART SERIES: Aluminum in the Columbia Gorge

The story of how the waste got to the landfills dates to the late 1970s.

Records regarding the remediation of the Recycled Aluminum Metals Company (RAMCO) site at Dallesport, Washington, provide a detailed account of a significant portion of smelter waste’s ultimate fate in the region. Its history can be tracked through the published chronology of decisions made by the Port of Klickitat Commission from 1979 through 2006.

In preparing this report the author examined dozens of documents from the Environmental Protection Agency, Washington Department of Ecology, Oregon Department of Environmental Quality, Port of Klickitat and other sources. Records regarding remediation of the Recycled Aluminum Metals Company (RAMCO) site at Dallesport, Washington, provide a detailed account of a significant portion of smelter waste’s ultimate fate in the region. This history is traced through the Port of Klickitat Commission’s chronology of decisions 1979-2006. No government agency or private business responded to requests from Columbia Insight for interviews or comment for this report.

RAMCO waste

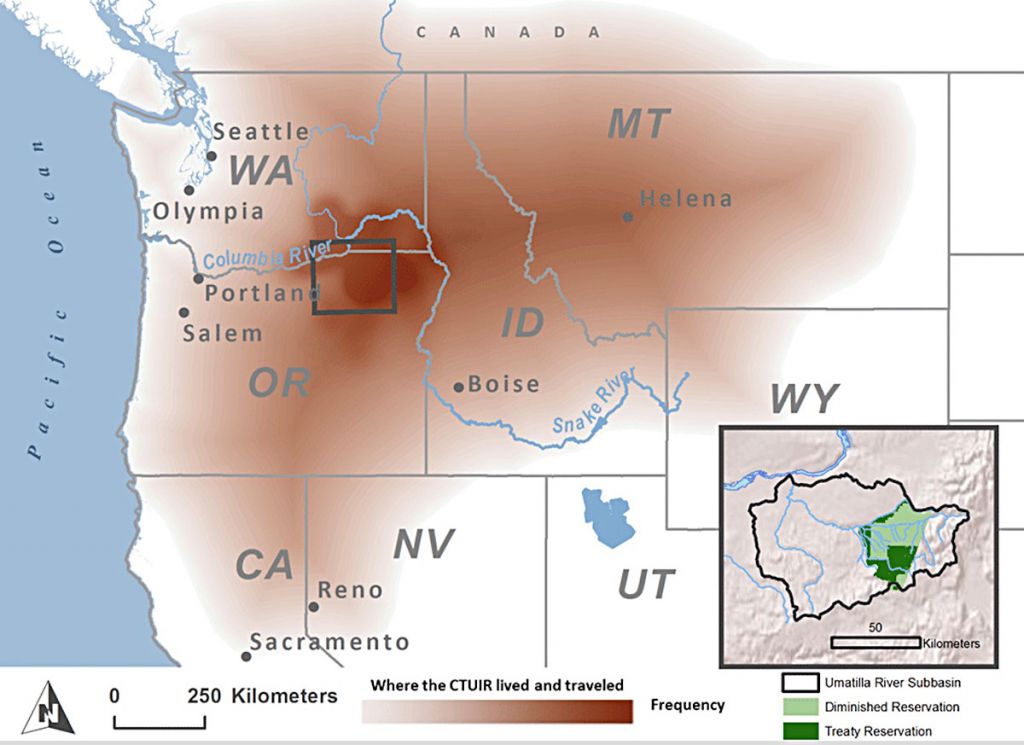

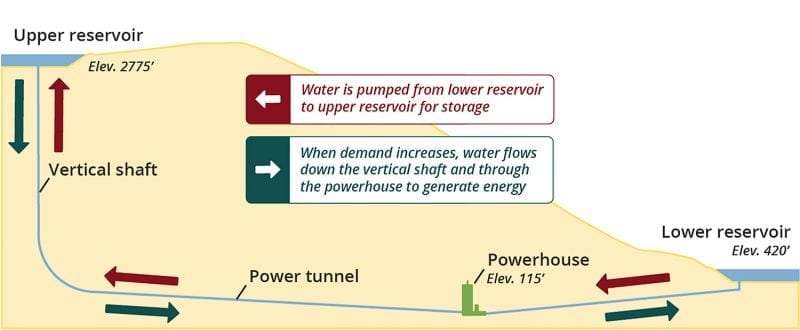

In 1979, RAMCO (originally named R.A. Barnes Company) leased space at the Dallesport Industrial Park, which is owned by the Port of Klickitat. The company extracted residual aluminum from wastes produced by smelters in Goldendale, Washington, and The Dalles, Oregon.

RAMCO skirted environmental responsibility from its inception. For example, in a 1979 modification of its original contract with the Port, RAMCO proposed building an addition to its plant “dedicated to inside storage of byproduct ‘to eliminate the need for a waste discharge permit,’” according to a chronology of the Port’s decisions. (The Port’s documents universally refer to the waste left after RAMCO’s reprocessing as a “byproduct.”)

Developing story: About 75 miles west of Dallesport and the RAMCO site, the former Reynolds/Alcoa factory and later Superfund site in Troutdale, Oregon, has been transformed into an industrial jobs center and natural wetland area. The site is now occupied by a FedEx Ground distribution hub (left), Amazon Distribution Center (right) and Troutdale Airport (top right). Photo by NASHCO

It wasn’t long, however, before RAMCO turned a shallow depression on Port property into an unlined landfill. This ad hoc landfill was located a few hundred feet west of Spearfish and Joe’s Lakes, traditional fishing sites used by Indigenous communities for millennia.

According to Port records, both the Port and RAMCO relied on a 1981 opinion issued by the Southwest Washington Health District that “the material from the Barnes Plant [RAMCO] is non-hazardous and land-fillable.” This was a curious justification for the waste disposal given that Health Districts are not the appropriate governing regulatory agency—landfills are regulated by the state and the EPA.

MORE: Dumps, dross and dust: Tracking aluminum waste in the Gorge

In addition, according to a 2006 Washington Department of Ecology cleanup report, an early engineering study concluded that the basalt layer underlying RAMCO’s landfill was solid and would not allow the waste to reach groundwater. Ecology also noted the waste had passed an acute fish toxicity test early on.

It reviewed other tests suggesting the waste was not reactive—that is, it was unlikely to produce chemical processes that could cause trouble. This despite the fact that aluminum is well known to be extremely reactive with numerous other elements.

Turbulent partnership

The Port had initially been attracted by RAMCO’s promise of 40 jobs and the possibility of “a worth in excess of a million dollars.” But its chronology shows RAMCO had management and financial difficulties almost immediately.

By 1982, RAMCO was withholding its rent to the Port in a conflict over an electrical fire. The next year it sued the Port over an insurance dispute. A year later it demanded a new waste disposal site at the Port.

In 1989, RAMCO started sending waste to the Wasco County Landfill (WCL) in The Dalles, but in May 1990 it complained to the Port that the WCL’s fee of $20,000 a month was “making their business operation financially unsound.”

Out of the way: With Mt. Adams visible in the distance, the Wasco County Landfill near The Dalles, Oregon, stores aluminum waste. Photo by Jurgen Hess

The Port responded by instructing its engineer to find a place on Port property for the waste. This spot turned out to be next to the RAMCO building, where a pile of waste soon developed.

The pile drew Ecology’s attention. The Port defended RAMCO when Ecology alleged the company was dumping waste without a permit. By 1991, RAMCO wanted Ecology to remove the classification of its waste as “dangerous.”

This did not happen immediately.

According to a 2011 EPA cleanup contractor’s report, in 1993 RAMCO had tested salt cake, which comprised the majority of its waste, and found it met the state’s definition of “dangerous,” as the salt cake was an aquatic toxin. This finding conflicted with the prior fish toxicity test as well as the Southwest Washington Health District opinion from 1981. The finding came after an unknown amount of waste had been sent to the WCL between 1989 and 1991.

Waste removal

Ecology initially considered the waste problematic, but later changed its position. After RAMCO went out of business in 1994, Ecology agreed to allow transport of the open waste pile next to RAMCO’s building either to the Roosevelt Regional Landfill upriver in Washington or the Columbia Ridge Landfill near Arlington, Oregon.

Approval depended on the waste being crushed and dried, which Ecology decided would reduce its potential for problems in a landfill; Ecology would then remove the state’s “dangerous” classification.

By 1995, about 21,433 tons of the waste had been sent to Roosevelt. Ecology judged that Roosevelt’s “gas and leachate collection systems and liner could adequately deal with disposal of the open stockpile of salt cake from RAMCO.” (Columbia Insight’s investigation found no record showing the Wasco County Landfill could handle such waste prior to its 1989-91 acceptance of RAMCO waste, or during Ecology’s mitigation efforts in the mid-1990s.)

By 1995, about 21,433 tons of the waste had been sent to Roosevelt. Ecology judged that Roosevelt’s “gas and leachate collection systems and liner could adequately deal with disposal of the open stockpile of salt cake from RAMCO.” (Columbia Insight’s investigation found no record showing the Wasco County Landfill could handle such waste prior to its 1989-91 acceptance of RAMCO waste, or during Ecology’s mitigation efforts in the mid-1990s.)

Although Ecology had removed the waste pile next to RAMCO’s building, little had been done about the waste in RAMCO’s unlined Dallesport landfill. In 2005, Ecology reevaluated it, drilling boreholes and testing wells. These efforts produced reports of a “strong odor of ammonia” and high temperature groundwater—indicating chemical reactions occurring below the surface.

Other tests showed that nitrates and salts exceeded water quality standards in groundwater at the site, and that cyanide, chromium and other substances exceeded the EPA’s maximum contaminant level and could leach from the soil.

[perfectpullquote align=”full” bordertop=”false” cite=”” link=”” color=”” class=”” size=””]For most of the public, aluminum waste is now “out of sight, out of mind.”[/perfectpullquote]

Ecology assigned the RAMCO site a hazard ranking of two on a scale of five, with one being the most hazardous. The agency began a cleanup in 2007 and approved sending most of the waste—principally salt cake—to the Wasco County Landfill.

By 2009, it had supervised removal of about two-thirds of the RAMCO waste. But funds from RAMCO and Ecology were inadequate to complete the task.

The EPA then took over. It designated the problem as urgent and completed remediation in 2010. The EPA sent a $2.1 million bill to the Port of Klickitat. Litigation ensued. In a 2015 consent decree, the Port agreed to pay the EPA $2 million.

Risk of fires, explosions

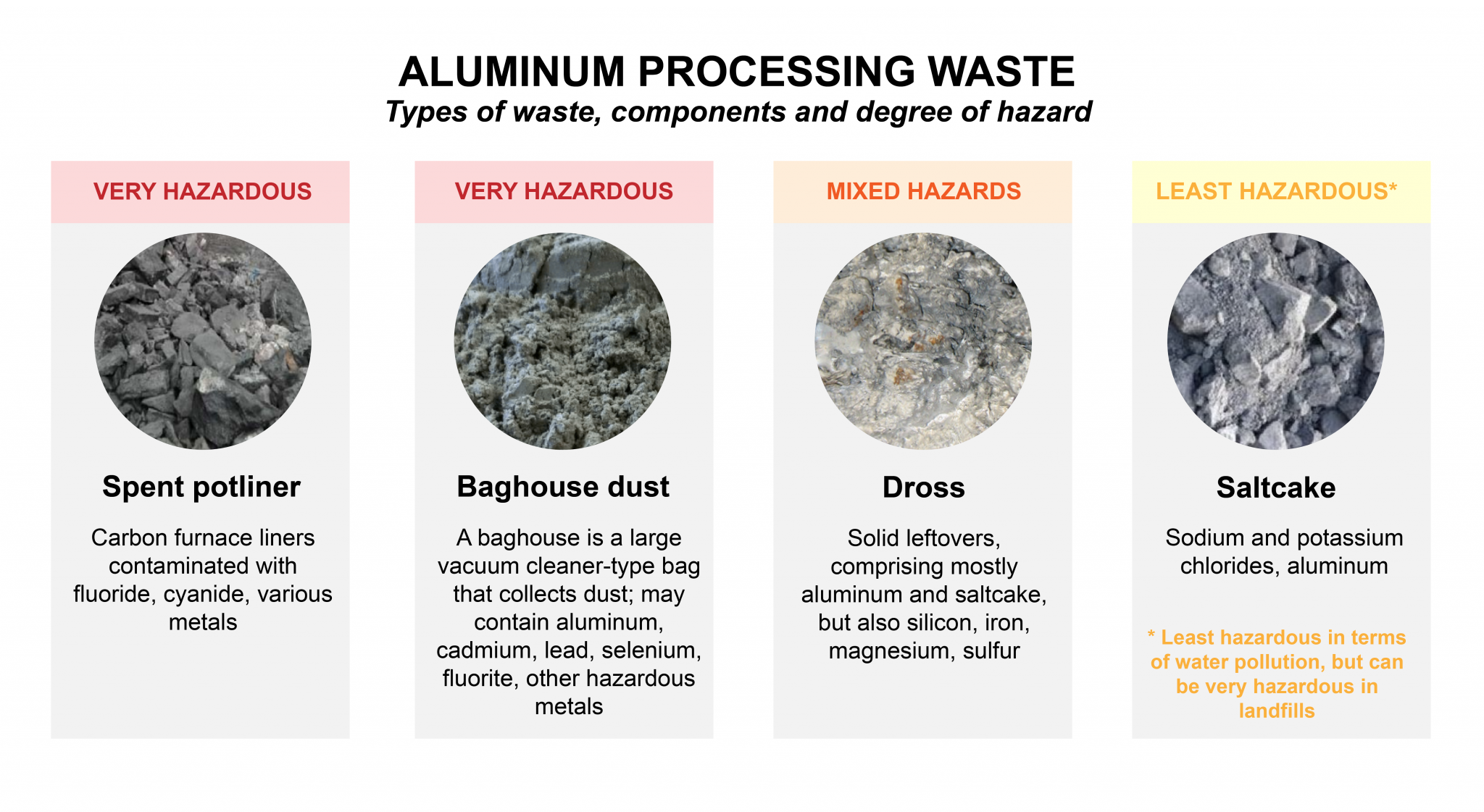

Concerns about waste vary depending on whether it’s in situ and un-remediated or removed and sequestered from the general environment. Regulations regarding disposal of aluminum waste are confusing.

The U.S. government and Oregon DEQ use the term “hazardous,” while Washington uses “dangerous.”

The EPA’s criteria for determining hazard in landfills are ignitability, corrosivity, reactivity and toxicity.

The agency has never ruled that aluminum waste is hazardous, despite the metal’s propensity to react and ignite in some circumstances. Thus it’s not actually illegal to dispose of aluminum processing waste in a municipal solid waste landfill, even though the EPA has expressed mounting concern about the practice.

The main environmental concern regarding the waste while it was at the Port was risk to surface water, groundwater and soil from cyanide, chromium, nitrates and salts. But landfills present more complex hazards. Managers are required to monitor not only landfill leachate—fluids that trickle through the waste and collect at the bottom above the liner—but also the numerous gases that are generated as the waste decomposes both with the help of microorganisms and through abiotic processes.

In addition, aluminum waste may undergo unanticipated chemical reactions with the myriad kinds of trash it encounters in municipal solid waste facilities. The DEQ required the WCL to store aluminum waste separately from general waste and keep it away from the leachate.

When the EPA took over the remediation project it decided, with Ecology’s agreement, to separate the remaining waste into gradations of hazard and dispose of each category differently.

Going underground: The Wasco County Landfill is located approximately six miles south of Interstate 84 using exit 87. Photo by Jurgen Hess

To make the salt cake and dross less problematic, the EPA approved a plan to break the waste up into smallish chunks, spread it out and let it “aerate” for a period of time before it went to the WCL. This would reduce—but not entirely eliminate—the risk of water-aluminum reactions, generation of ammonia and other gases, and therefore the risk of fire and explosion.

Salt cake is the least hazardous of aluminum waste types. But it can contain plenty of aluminum. Ecology found RAMCO’s salt cake contained about 28% aluminum.

MORE: Pollution from aluminum still an issue in The Dalles

Aluminum can “self-heat” and explode in contact with water. Landfills are usually hotter than the surrounding landscape because decomposition produces heat. A warm environment can trigger further chemical reactions involving aluminum. These may produce acetylene, ammonia, hydrogen and methane. Thus aluminum may cause fires in landfills that can’t be extinguished with water.

About 19,000 tons of salt cake and possibly other material labeled “non-hazardous dross material” went to the WCL under EPA supervision. An additional 24 tons was sent to an aluminum recycler for further recovery of the metal. About 16 tons of very hazardous waste went to Chemical Waste Management of the Northwest near Arlington, the only hazardous waste landfill in Oregon.

Legal but problematic

The total amount of aluminum waste remaining in landfills and on closed smelter sites in the Columbia River Basin is unknown. Available documents don’t address the amount, composition and disposition of the tons of waste sent to the WCL by RAMCO from 1989 to 1991. According to Ecology, by the time remediation actions were complete, about 135,000 tons of material had been removed.

As far as Columbia Insight’s investigation can determine, approximately 49,000 tons of that waste is in the WCL.

In 2009, the WCL also accepted about 5,300 tons of waste from the Goldendale smelter as it was being demolished.

New memories: On the 700-acre former Reynolds Metal Superfund site, the 40-Mile Loop Trail at the Troutdale Reynolds Industrial Park is part of a Port of Portland reclamation effort. Photo by NASHCO

Although it’s not illegal to dispose of aluminum waste in municipal solid waste landfills, the Oregon DEQ requires a special permit to do so. But the WCL did not have that permit when it accepted both aluminum waste and an unrelated toxic, flammable industrial waste in the 2000s. The WCL experienced two fires in 2006.

Ignitability is one of the waste characteristics landfills are required to manage carefully under the federal Resource Recovery and Conservation Act. Municipal solid waste landfill fires in the United States are relatively common, averaging 839 annually, and secondary aluminum processing waste is increasingly considered “a potential source of landfill fire” by experts.

The EPA estimates that nationally nearly 3 million tons of aluminum waste was landfilled in 2018. Given the rapid growth of aluminum use, much more waste is likely to be produced in the future as more aluminum is recycled. It has to go somewhere. MSW landfills are probably not the right place.

MORE: Aluminum’s legacy continues to hang over the Gorge

Public documents regarding the two fires in 2006 at the WCL present radically different explanations of the blazes.

WCL told the DEQ in a September 6, 2006, report that the first fire, on August 22, was caused by a “hot load”—that is, it was already burning when it arrived at the landfill—and was extinguished with water. This explanation was repeated in a March 7, 2007, fire risk assessment conducted on behalf of Waste Connections, the parent company of the WCL.

As for the second fire, the WCL told DEQ it occurred in the early hours of September 4 and was extinguished with water by 2 a.m.

A DEQ inspector visited the WCL the day after the second fire and accepted management’s explanation of the cause.

Remnant: Aluminum scrap at the present-day Hyrdo Extrusion facility in The Dalles awaits recycling. Photo by Jurgen Hess

However, the fire consultant’s report six months later said the fire took all day to control and was extinguished with soil rather than water. The consultant had talked to landfill workers, who believed the fire occurred because water had contacted a material the landfill was illegally receiving—anhydrous magnesium chloride.

The consultant concluded that a “combination of events resulted in a ‘Perfect Storm’ scenario that ultimately resulted in fires.” The fires’ connection with anhydrous magnesium chloride did not become known to the DEQ or the public until significantly later.

Between 2000 and 2008, the Wasco County Landfill took in 7,900 tons of anhydrous magnesium chloride waste from production of titanium and zirconium at Oregon Metallurgical in Albany and TDY Industries in Millersburg. Magnesium chloride, like aluminum, is likely to explode when it encounters water. The WCL was one of four Oregon landfills that took in a total of 160 million tons of anhydrous magnesium chloride from the Willamette Valley companies.

In 2014, the EPA fined the Willamette Valley companies a total of $825,000 for illegal dumping of the material. The WCL pleaded ignorance and was not cited.

Waste Connections Vice President John Rodgers told Columbia Gorge News the magnesium material was not “deemed or designated by any agency as hazardous” and the landfill stopped accepting it as soon as it learned otherwise.

The WCL hasn’t responded to Columbia Insight’s queries for information and comment.

Unseen history: The Sandy River Delta is a popular recreation area. In the 1950s and ’60s, area farmers filed several lawsuits against Reynolds Metals saying they were poisoned by toxins spewed out by the company’s aluminum operations in Troutdale. Photo by NASHCO

The period when WCL accepted anhydrous magnesium chloride overlapped with about a year of its acceptance of aluminum waste. Despite the fact that the DEQ is the controlling agency for Oregon landfills, the EPA, the Washington Department of Ecology and various contractors worked out procedures with WCL to transfer RAMCO waste—nobody informed the DEQ of the transfer. In fact, the agency didn’t know about either the RAMCO waste or the anhydrous magnesium chloride waste until 2009.

When the DEQ did learn of the illegal disposal, the agency asked WCL to provide “a copy of the Department-approved special waste management plan for accepting and disposing of hazardous substance contaminated waste” from RAMCO. It discovered there wasn’t one.

The agency expressed concerns about “self-heating and ammonia-generating properties” of the RAMCO waste if it contacted water. It also observed the overlap in time with the landfill’s acceptance of anhydrous magnesium chloride. The landfill’s role in the latter violation wasn’t resolved until 2014.

Lingering issues

The legacy of aluminum processing in the mid-Columbia River Basin extends far beyond the factories themselves. It will last lifetimes.

It took almost 30 years to clean up the waste from two smelters and a reprocessing plant, during which time communications and actions by a private landfill company and state and federal regulatory agencies were less than straightforward.

For most of the public, aluminum waste is now “out of sight, out of mind.” But it still poses hazards ranging from groundwater contamination to fires and explosions.

Problems at municipal solid waste landfills may re-emerge unless the EPA resolves its policy contradictions to require disposal in different facilities. So far the waste products of the long-gone aluminum industry in the Columbia River Gorge haven’t produced widespread environmental or health disasters, but it’s clear from the historical record that this state of affairs is as much due to luck as it is to wise decision-making and safe disposal practices.

READ THE FULL 4-PART SERIES: Aluminum in the Columbia Gorge

Infographics by Mackenzie Miller.

Columbia Insight‘s series focusing on the aluminum industry in the Columbia River Gorge is supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.

Columbia Insight‘s series focusing on the aluminum industry in the Columbia River Gorge is supported by a grant from the Society of Environmental Journalists.