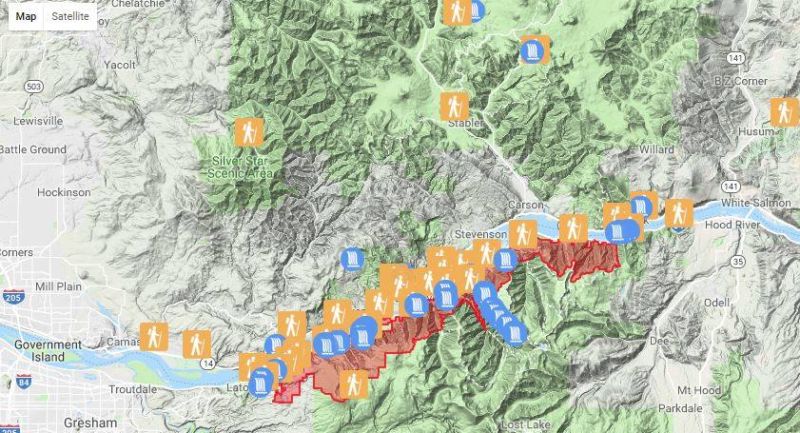

Interactive map shows trail closures in the Gorge

Check out Friends of the Columbia Gorge’s updated Find a Hike page, which features an interactive map of trails in the Columbia River Gorge National Scenic Area. The map has been updated to show the Eagle Creek burn area and it takes trail closures into account, making it an excellent resource for anyone planning their next hike in the Gorge.