250,000 juvenile steelhead gone after hatchery failure

Washington officials blame equipment malfunction for loss of the bulk of Lyons Ferry Fish Hatchery’s Wallowa stock summer steelhead

Out of there: Lyons Ferry Fish Hatchery was built in 1982 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Photo: WDFW

By Eli Francovich. February 7, 2022. Nearly 250,000 steelhead smolts escaped from a rearing pond on the Snake River in Washington after an equipment failure last week.

The juvenile steelhead, which were slated for release later this spring, were being held at the Lyons Ferry Fish Hatchery on the Snake River, south of Palouse Falls in Washington.

On Jan. 31, Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife staff discovered that a rubber gasket sealing a screened rotating drum had disintegrated leaving an inch-and-half gap leading to the Snake River.

The loss accounts for about 64% of Lyons Ferry Hatchery’s Wallowa stock summer steelhead set for release in 2022 and 8% of the overall hatchery steelhead production in the Snake River basin, according to WDFW.

“We’ve never had this happen, staff do an annual check when those ponds are drawn down,” said Chris Donley, WDFW’s eastern region fishery manager.

Donley doesn’t believe the failure was a staff mistake, categorizing it as an equipment failure.

Possibly eaten by predators

The 249,770 smolts may have survived, but only if they escaped recently. If so, anglers may see a higher-than-normal number of steelhead returning to Lyons Ferry in 2023.

If they escaped earlier in the year they likely were eaten by predators.

The smolts were destined for Washington’s lower Grand Ronde River.

MORE: Tribes in the Upper Columbia River Basin are reintroducing salmon to local rivers

A smolt is a juvenile salmon or steelhead fish, between 12 and 15 months old. WDFW and other state wildlife agencies rear smolts and transport and release them to various areas in the state.

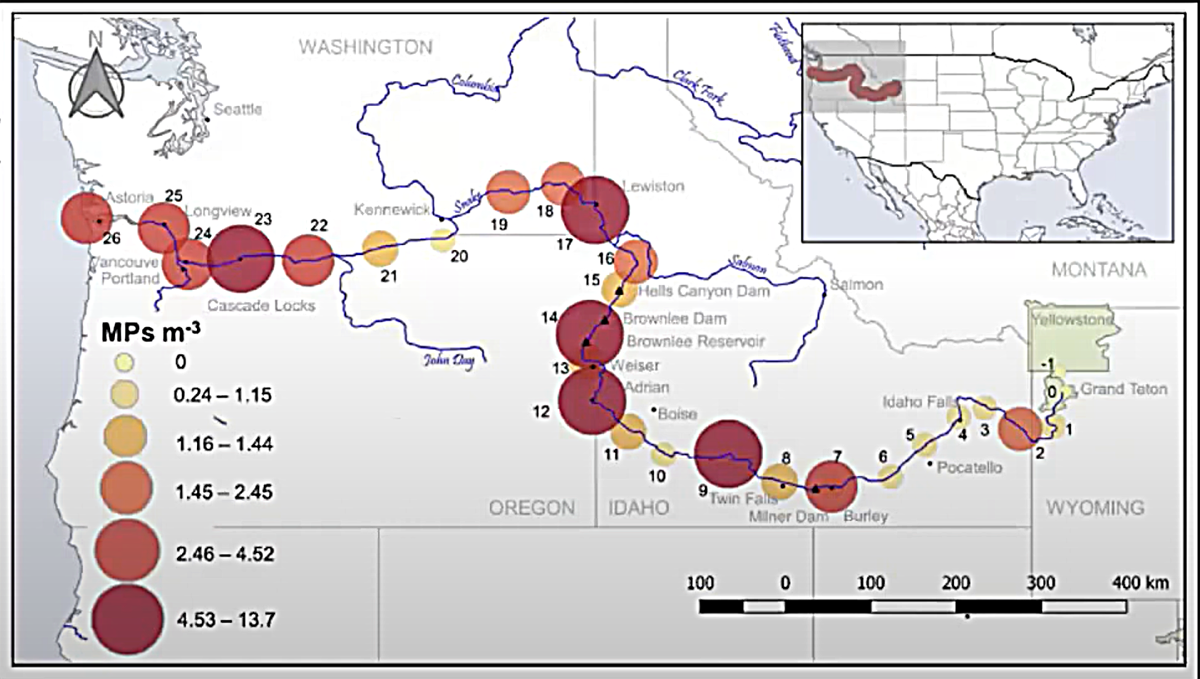

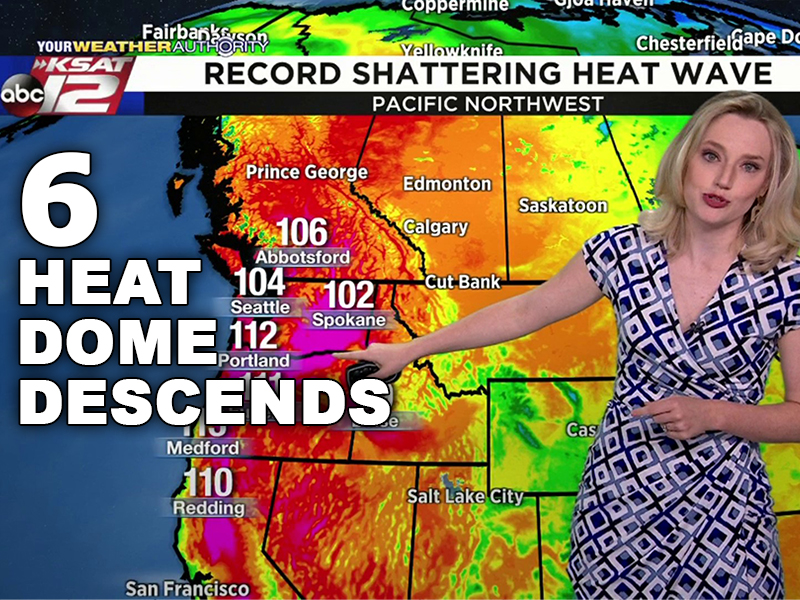

On its own Donley says the loss is manageable. However, combined with poor ocean conditions, slowed river flows due to dams and warm summertime water Donley characterized the escape as “one more death by a thousand cuts” to recreational steelhead fishing.

Both wild and hatchery-reared steelhead and salmon struggled to survive on the Snake in 2021. In response managers in Idaho and Washington limited and in some cases closed steelhead fishing, with some managers calling it the “worst ever.”

Get weekly updates from Columbia Insight.

Advocates for wild fish and a dam-free Snake River say the incident highlights why natural systems are preferable.

“Every time we see hatchery failure it reminds us of the importance of restoring habitat and wild fish,” said Gregory Fitz, communications manager for the Wild Steelhead Coalition. “We want to see natural systems work because they are more resilient.”

Eli Francovich is a journalist covering conservation and recreation. Based in eastern Washington he’s writing a book about the return of wolves to the western United States.