The hatchery crutch: How we got here

From their beginnings in the late 19th century, salmon hatcheries have gone from cure to Band-Aid to crutch. Now, we can't live without manufactured fish

Hatchery chinook salmon smolts released into a net. Photo: Cavan Images/Alamy Stock Photo

This story was originally published in Hakai Magazine and is reprinted here with permission. Visit their website to read three other stories in the series, "The Paradox of Salmon Hatcheries."

By Jude Isabella, June 9, 2022. Writer and fly fisher Roderick Haig-Brown dreamed of a time when the North Pacific Ocean would grow a lot more salmon.

Haig-Brown was probably the most famous and influential fly fisher in North America during his lifetime.

The author wrote from his home on the banks of Campbell River on Vancouver Island, British Columbia. He sat at a desk with a view of the river, far from where the arbiters of great writing resided at the time. The New Yorker regularly reviewed his books (always favorably) and in 1976, the New York Times reported on his death.

From the 1930s to the 1970s, Haig-Brown led readers into the realm of Pacific salmon: chinook, sockeye, coho, chum and pink.

In his 1941 book, Return to the River, a lyrical story about one fish that moved a critic to call the author an immortal in the field of nature writing, Haig-Brown dug into the soul of a fish. He created a world from a wild chinook salmon's point of view, allowing the reader to tag along on the cyclical path of a fish named Spring, from birth to death in an Oregon stream.

Her life story is both wondrous and harrowing. Spring's journey reflected all that Haig-Brown fretted about over 80 years ago: logging that decimated streams, dams that blocked rivers and development that buried creeks.

MORE: 140 miles: The Snake River dams stranglehold

He fretted about hatchery fish, too.

Haig-Brown clearly understood salmon and what they needed to thrive. They needed habitat, not hatcheries. And yet Haig-Brown, like many in the Pacific Northwest, also wished for more fish.

Sometimes we get what we wish for, but we don't get what we want or need.

Today, wild salmon populations are struggling in the Pacific Northwest of North America. And yet, there are more salmon in the North Pacific Ocean than there were a century ago—more than when Haig-Brown wrote in his 1964 book Fisherman's Fall that he was "optimistic enough to believe that the North Pacific Ocean can grow a lot more salmon than are using it right now; and I hope I shall live long enough to see its capacity become a question of immediate moment."

The capacity of the ocean is a question of immediate concern.

There are at least 243 hatcheries strung along salmon habitat from California to Alaska and more feeding fish into the North Pacific via hatcheries in Russia, Japan and South Korea. Cannery operators in Oregon built the first salmon hatchery on the West Coast to supplement their catches in the late 19th century.

Annually, since 1988, the five salmon-producing countries release over 5 billion hatchery salmon.

Most hatcheries are industrial affairs. Eggs and sperm come together in white plastic buckets and fry are released after some months of growth. With streams so degraded—more like tenements than habitat, crowded with juvenile wild and hatchery fish, living fin to fin, competing for food and ripe for diseases and parasites—some hatcheries avoid problem environments by trucking their juvenile salmon to better release sites.

Hatchery fish also diminish the genetic robustness of wild salmon when, later in their lives, they enter spawning grounds and interbreed.

And, like boats, hatchery fish are money pits. How much a hatchery salmon costs varies per hatchery, but 20 years ago, a researcher calculated that to keep salmon swimming in the Columbia and Snake River basins in Oregon, Washington and Idaho, the price tag was $400 per fish.

By the time Haig-Brown published his first book in 1931, the science had already aligned against fish hatcheries.

In his writings, Haig-Brown shared a vision for restoring and protecting salmon habitat, instead of relying on hatchery fish—how did we get so far from his ideals? At first, it was mainly politics and blind faith in technology.

Today, the reliance on hatcheries is a combination of politics, law and desperation.

Playing God with fish

Almost a century ago, a Canadian scientist revealed that hatcheries were at best failed experiments, and at worst monuments to delusional thinking.

In the early 1920s, fisheries biologist Russell Earl Foerster arrived at Cultus Lake, which drains into the lower Fraser River in British Columbia, to run a salmon hatchery built by the province 10 years earlier. He floated the idea of establishing a research station as well.

Foerster had a few questions, including whether raising fish in hatcheries worked: were the wild runs of salmon at Cultus less or more productive compared with the hatchery fish raised at a creek downstream of the lake?

Without any evidence that playing God with fish was a good idea, hatcheries had proliferated across the Pacific Northwest after the U.S. government built the first national hatchery in 1872 in California. Canada built its first West Coast hatchery in 1884.

Salmon runs were already diminishing, but there was no political will to protect or restore habitat: fisheries managers declared artificial spawning the price of progress, an economic journey measured in dollars, mostly benefiting the few who ran timber companies, mining operations and canneries.

When the University of Washington (UW) launched a fisheries department in 1919, students studied canning technology and fishing methods. It took 10 years for the focus to switch to biology and conservation.

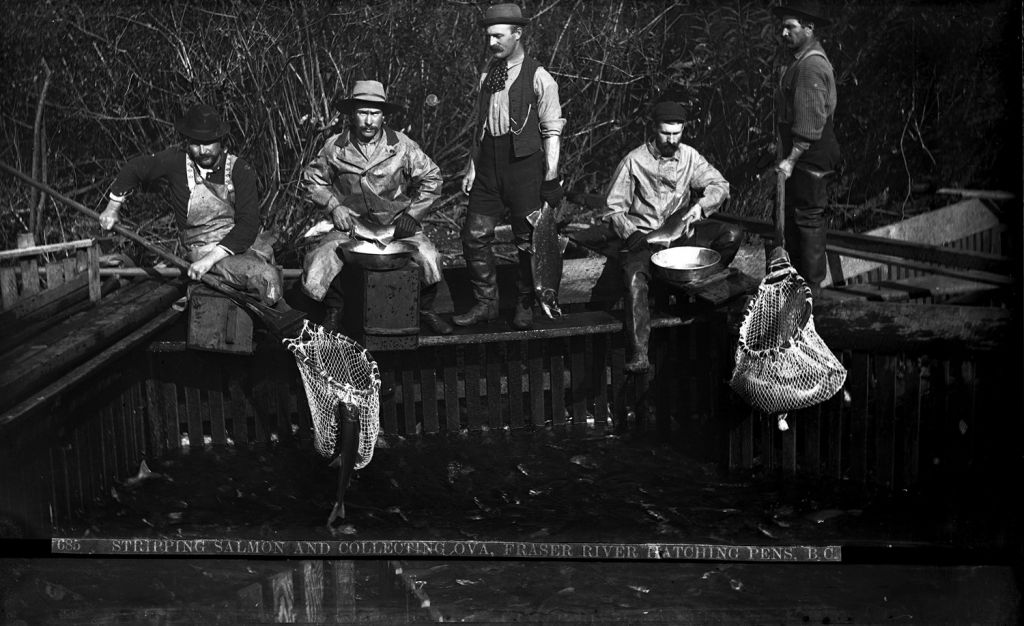

An early hatchery on the Fraser River in British Columbia sent out workers to strip salmon of eggs and sperm without thought to how salmon populations evolved in particular streams. Photo: Bailey Bros. Photography/Vancouver Public Library 19960

Spring, the chinook at the center of Return to the River, ran a gauntlet of development for almost 500 kilometers that her ancestors had not, Haig-Brown wrote: "There were poisons in it and obstructions across it and false ways leading from it." She is terrified when a spillway tosses her to the base of a dam. As she swims past Vancouver, Wash., and Portland, the Columbia River is a nasty stew containing the foulest of ingredients—sewage and industrial waste—but the strongest fish make it: "Overburdened with death and decay there was still in it enough life to support their brief passage," Haig-Brown wrote.

Salmon Nation, the Pacific Northwest region that Indigenous communities had successfully managed for thousands of years by understanding what salmon, and in turn humans, need to thrive—a home—became a giant experimental lab. Playing around with salmon ruled the day.

At Cultus Lake, researchers tested hybridization between salmon species, they transplanted eggs far from natal streams and they experimented with fish feed for hatchery fry. When beef liver became too expensive as feed, researchers compared salmon offal, canned salmon and halibut meal. Nothing was nearly as good as beef liver, and halibut meal produced the smallest fish, if it didn't outright kill them.

MORE: Thermal hopscotch: How Columbia River salmon are adapting to climate change

Foerster's 12-year experiment comparing hatchery sockeye and wild runs became a classic in the field of salmon research. He showed for the first time—in a published scientific paper, the language of newcomers to the land—that in the early stages of salmon development, most fish die.

As eggs hidden beneath gravel, salmon are vulnerable to the fish, raccoons and ducks that find them. As alevin with yolk sacs still attached to their bodies, flies and other small creatures eat them. As fry, salmon can escape some predators, but they're still food for great blue herons, bigger fish and other hungry animals.

Foerster also found that artificially fertilized eggs hatched at higher rates than naturally fertilized eggs. And he determined that when hatchery managers incubate and release fry, juvenile salmon flood a stream. More fish!

There was, however, a very big but: hatchery-raised fish were no better at returning from the ocean. Over the years, we've come to know hatchery salmon often lack the skills to navigate life the way Spring does, learning life lessons like what to eat—not all tiny things in the water are edible—and that a dark head against a light sky could be a killer.

The early advantage for hatchery fish, Foerster showed, failed to hold. What, then, was the point of spending money on artificially raising and feeding salmon?

[perfectpullquote align="full" bordertop="false" cite="" link="" color="" class="" size=""]Salmon hatcheries are the sum of poor choices made over 150 years by fisheries managers, often having no idea what they didn't know about salmon, habitat and the ocean.[/perfectpullquote]

When Haig-Brown was writing Return to the River at his desk in longhand, the hatcheries he worried about were in the United States. During Spring's return journey, when she and her cohort are so close to their home stream they can smell it, a wooden rack strung across the river blocks the salmon—fisheries managers plan to strip them of eggs and sperm for a new hatchery.

The fish are restless: "Once more, for the twentieth time or the fiftieth time, Spring came up to the rack. She worked along with less patience now, turning away from it, turning sharply back, rolling heavily in the strong current so that her back showed and went down before the quickening movement of her tail."

By 1934, understanding that running a hatchery was about the same as tossing cash directly into the ocean, the bureaucratic precursor to Fisheries and Oceans Canada (DFO) decided against them. In 1937, Canada's federally run hatcheries closed. Fisheries scientists in Alaska confirmed Foerster's findings and Alaska hatcheries closed, too.

In the book Making Salmon, historian Joseph Taylor points out that closing the hatcheries was a victory for fiscal restraint that masqueraded as a triumph for science.

Foerster presented his work at a 1929 fisheries conference in Seattle. As the Depression deepened and government budgets shrank, so did enthusiasm for hatcheries, but it was a lot easier to close them where spawning habitat remained relatively intact, in British Columbia and Alaska.

Salmon fry emerging from their eggs. Photo: Stock Connection Blue/Alamy Stock Photo

Farther south, a mishmash of jurisdictions, a cozy relationship with industry and a larger population clamoring for more development and more hydroelectric power cemented hatcheries as the fisheries policy of choice.

It's not that British Columbia has no dams, but there are fewer than in the U.S. Northwest.

In the 1950s, Haig-Brown led a commission that studied the environmental effects of building a dam just over 300 kilometers from the mouth of the Fraser River in British Columbia. To build a dam, he wrote, "was a betrayal of salmon and their meaning," that the fish's value was far more than economic, and preserving the salmon was "an act of faith in the future." The dam project died.

Taylor, a fisherman turned academic, teaches history at Simon Fraser University in British Columbia. Early on, he says, hatcheries were simply a political panacea.

"Fish culture emerged as a default solution to a problem around the politics of land use," Taylor says. "That's really the story."

But by the 1960s, hatcheries had stuck around long enough for managers to be lulled into thinking technological improvements—new drugs to control disease, better feed—would make the next wave of hatcheries the best thing in fisheries since the invention of the boat engine. But really, it's more like a stubborn belief that salvation lies in technology, and that trumped good old-fashioned conservation.

The hatchery gamble

Haig-Brown always insisted that streams needed protection, but he also felt the siren call of technology and its promise of problem-solving.

In Return to the River, the main human character, the Senator, believes the fisheries biologists he meets: "these white-coated young men were the symbol of America's salvation."

By the time Haig-Brown updated an edition of Fisherman's Fall in 1975, the annual catch in most salmon-fishing countries was dropping again.

"I am convinced that the only thing that can restore the sport to its former splendor is more fish, and I am equally convinced that it is perfectly possible to have more fish," he wrote. If better technology could produce more fish, he was in.

In 1974, Peter Larkin, the first provincial fisheries biologist in British Columbia, wrote an influential essay, "Play It Again, Sam—An Essay on Salmon Enhancement," that's equal parts enthusiastic and skeptical. Larkin spells out the foibles humans might bring to hatcheries and other means of boosting fish populations: the lack of continuity in research, the lack of true experimentation and muddy goals.

But, as Larkin noted, "Politically, salmon enhancement is a 'natural.'" The other option was to cut the fishery.

Larkin called salmon enhancement a gamble, but one worth taking.

MORE: Salmon are no longer kings of the Columbia. That has biologists worried

Canada reversed its earlier decision and gambled that technology could restore populations and double the annual commercial catch by 2005, launching the Salmonid Enhancement Program (SEP) in 1977. They funded hatcheries and spawning channels and fertilized lakes and streams to promote the growth of fish food.

In the early 1980s, the University of British Columbia hired Ray Hilborn, today a well-known fisheries scientist at UW, with funding provided by the SEP.

"It was a total failure," Hilborn says of the program. The catch went down. "It did nothing to improve Canadian fisheries," he says, though he adds that it's tough to say what would have happened without the program.

Still, by 2005, the commercial catch had almost halved from 1970s levels, at 31,811 tons, or 54.6% of the average. By 2019, the catch was 3,423 tons, or about 5% of the catch 42 years before.

With artificial spawning channels—a form of salmon enhancement—water flow and depth can be controlled to create ideal spawning conditions and boost juvenile survival. But by inflating a single population over others, artificial spawning channels can lead to lower salmon diversity in a watershed. Photo: Donna MacIntyre/Lake Babine Nation

Alaska, like British Columbia, revisited its hatchery policy in the 1970s amid salmon declines, and officials there also decided the time had come to invest in salmon enhancement.

In Washington, already dotted with hatcheries, a year after the SEP launched, the state began its own program to double the salmon harvest through hatcheries. Runs were on the decline, and again, reducing fishing pressure is never popular even if it's the right thing to do.

Plus, a series of court rulings that gave Indigenous communities back their rights to fish apparently panicked fisheries managers: the state poured $30 million into tribal programs over more than 10 years. Tribes built their own hatcheries to guarantee access—enshrined in treaties and through the law courts—to salmon. These hatcheries keep alive Indigenous cultural practices.

Larkin wisely surmised that the rush to build hatcheries and other enhancements was swept in on a prevailing mood of optimism that this time things would be different.

"In one blow, two problems could be solved," Larkin wrote in 1979, "how to find enough fish to occupy the fleet, and how to compensate for the loss of salmon habitat."

Larkin's advice, to avoid past mistakes, was often disregarded. As Hilborn notes today, and in many papers in the past, ideas around monitoring outcomes and specifying clear, measurable goals fail to stick when it comes to many hatcheries and other salmon enhancements.

By 1994, an economist concluded that the economic costs of the SEP would exceed the benefits by CAN $600 million.

As Haig-Brown hoped, more fish swim the ocean, but they're not evenly distributed geographically.

Overall, salmon catches increased between the 1970s and 2010s—Russia's total catch increased by 4.9 times, and the U.S. catch, mostly in Alaska, went up 2.6 times. In Japan and British Columbia, catches decreased, whether fishers were harvesting wild or hatchery salmon—in fact, Japan's catch is almost entirely hatchery chum salmon.

The Canadian catch from 2019 to 2021 looks to be only 6.1% of the 1970s average.

Nor is the wealth of fish evenly distributed across species. In a 2018 study, fisheries scientist Greg Ruggerone and DFO scientist Jim Irvine shocked those who pay attention to salmon with the fact that the North Pacific hosted more salmon in 2015 than in 1925, when Foerster was at Cultus Lake.

"But the problem was, nearly 70% of those fish were pink salmon," Ruggerone says. In 2018 and 2019, more pinks returned to spawn than any year the scientists studied. "It was just phenomenal," he says.

And troublesome for other salmon species.

Over a 15-year time frame, Ruggerone and his colleagues found that hatchery chinook from the Salish Sea in Washington saw a 60% reduction in survival in the years they compete for food with the odd-year pinks.

"It's quite dramatic," he says.

Manufactured pinks are duking it out in the ocean with wild fish—and competing with other hatchery fish that may have a better reason for being there.

Conservation hatcheries sometimes offer the last hope for particular runs of fish: for instance, Russian River coho in Northern California, Snake River fall chinook in Idaho and Okanagan River sockeye in British Columbia. Those conservation efforts—paying attention to genetics, using locally adapted broodstock, raising juveniles in enriched environments, among others—are paying off, though barely for Russian River coho.

A whiff of desperation haunts hatcheries.

International cooperation missing

A strong whiff of nostalgia haunts Return to the River.

In 1941, Haig-Brown knew he was witnessing a fundamental change to the environment and the fishery. The Senator is, like the author, a fly fisherman and an adept naturalist who watches salmon probably more often than he catches them.

But like so many, the Senator acquiesced to "progress."

"For one more year they would spawn as they were meant to spawn, and fry and fingerlings would grow from their spawning as they were meant to grow, from the natural abundance of the river," Haig-Brown wrote. "And the rack might go out again or they might decide against using it another year. He played with his hopes, but he felt in his heart he was seeing the end of it, the last natural spawning of the chinooks that belonged to his river."

Here we are today, 80 years later, with an upended environment and with a grim duty to look around, take our bearings and say, "Well, where do we go from here?"

As Larkin wrote, clear goals are important. More fish, however, proved a simplistic, problematic and greedy goal.

Hatcheries are not cures for what ails Salmon Nation—they are interventions that, if used judiciously, may offer life support to a few patients. Sunsetting hatcheries because wild fish are thriving would be the ultimate success story.

To restore salmon populations requires a thoughtful, long-term vision. Habitat restoration is key, and in some instances a conservation hatchery that keeps distinct salmon populations alive during the long process of undoing extensive damage to watersheds.

Also, across the board, policies that separate hatchery fish and wild fish could give the fish more breathing room in their habitats.

"It's feasible," Hilborn says. "You can move the run timing of a hatchery stock quite readily; it doesn't take much selection to get them to come earlier or make them come later."

To cleave apart wild from hatchery fish, and the different populations, would mean a fundamental shift in the style of commercial fishing, moving toward terminal fisheries, in which weirs or traps, rather than hooks and nets, catch fish in the river on their way home to spawn.

Once standard practice from Alaska to Northern California and in Japan and Russia, weirs allow for more targeted fishing. On the lower Klamath River in Oregon and California, for instance, Indigenous managers erected a weir for 10 days during peak chinook migration, leaving it open at night to allow migration upriver to spawning grounds and to other communities.

With weirs, fishers can aim for hatchery fish, identifiable by a clipped adipose fin. An experimental fish trap near the mouth of the Columbia River in Oregon is a new take on the old technology, guiding fish into a trap where they can swim freely, and fishers can select which fish to harvest.

Salmon weirs and traps allow for more selective fishing, giving fishers the opportunity to separate wild fish from hatchery fish. Photo: Aaron Jorgenson/Wild Fish Conservancy

A weir could also help separate vulnerable wild salmon populations from the healthy ones, once a genetic baseline is established.

"You could do real-time DNA testing, that technology is available," says Michael Price, who studies salmon on the Skeena River on British Columbia's north coast. "I know this is a difficult thing to say, because you don't ever want to necessarily trade one livelihood for another, but if you move more of that fishery into the river, you still have commercial fisheries but they're more selective."

The Lax Kw'alaams Band has proposed fitting a fish trap on the Skeena River, where an abundance of hatcheries and artificial spawning channels has led to lower salmon diversity. Roughly 70% of the sockeye heading home come from one of those enhancements.

As Hilborn points out: none of those solutions addresses the disease or competition issues. Nor can anyone control the ocean.

But managers can control hatchery fish.

Right now, there is no shared vision across the five countries on the role of hatchery fish. Randall Peterman, a fisheries scientist and professor emeritus at Simon Fraser University, has called for international cooperation since the early 1980s.

Almost 40 years ago, Peterman and his colleagues had already noted the competition between salmon populations in the ocean. BC sockeye came back smaller and less abundant in years when the Bristol Bay, Alaska, sockeye were abundant. Any efforts at enhancing sockeye populations were a classic case of the law of diminishing returns—the effort and money sunk into enhancement did not translate into consistently more fish.

"And there have been numerous papers documenting that international linkage since then," Peterman says. "So this is not a country-specific problem. It's an international problem."

Only in the past couple of decades has salmon research focused on the ocean, now more unpredictable with climate change. Salmon are definitely responding to warming waters: pinks are having their day in the sun, while chinook and coho populations sputter along.

"The fundamental problem with chinook and coho is ocean survival," Hilborn says. "You won't solve that through stream restoration."

Lyons Ferry Fish Hatchery in Washington was built in 1982 by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers. Salmon hatcheries across the Pacific Rim release billions of pink salmon into the ocean ecosystem every year. Photo: WDFW

It seems logical that easing the burden on wild fish would interest all salmon nations.

"We need to be thinking in those terms," Peterman says. "You can't continue to pump out fish into a common pasture, the ocean, and expect continuous commensurate benefits."

Back in 1984, Peterman proposed a way to keep track of hatchery fish: create an international body to monitor and coordinate salmon enhancement, funded by a tax on each juvenile salmon released. Countries pumping out the most fish would bear most of the cost.

Today, Peterman muses about a cap and trade system, similar to the one used by British Columbia to control carbon emissions.

All five countries belong to the North Pacific Anadromous Fish Commission (NPAFC). That organization, however, has no authority to regulate hatcheries, says president Doug Mecum.

The NPAFC enforces a drift-net ban and shares information on production and survival trends of salmon among members. Fundamentally, each country is responsible for and has authority over their own programs, Mecum says.

"Ideally the different parties would come together in a forum on some sort of ongoing basis and say, 'Well, how are things going for your program and … for your program?'" he says. "'And have you thought about this, and have you thought about that, and can we have a conversation around that?' It sounds great, but I don't know how you would do it."

Plus, some scientists remain skeptical that ocean capacity is a problem.

Salmon hatcheries are the sum of poor choices made over 150 years by fisheries managers, often having no idea what they didn't know about salmon, habitat and the ocean. Magical thinking is no substitute for humility.

Even Larkin, when making a case for salmon enhancement, wrote: "but natural systems being what they are, there is always a good chance that our best efforts will turn out to do more harm than good."

The number of hatchery fish outmuscling wild in the North Pacific is not catastrophic. Not yet. The proportion of pink hatchery salmon, for example, is only 15% of the total pinks in the North Pacific, but what if that percentage grows?

Fisheries managers have faced political pressures and economic pressures countless times in the past.

"Managers don't act soon enough, the crisis is upon them. And then finally they act, but it's often too late," Peterman says. "Here's a case where we can get in sooner than usual. We just need to get ahead of this one."

If history is a guidebook, getting ahead of a crisis seems damn near impossible.

In his beloved classic from 1946, A River Never Sleeps, Haig-Brown wrote, "The salmon runs, more surely and easily than almost any other resource, can be made to last and serve indefinitely, can even be grown back to, or beyond, their full glory."

Will we let them?

This story was originally published in Hakai Magazine and is reprinted here with permission. Visit their website to read three other stories in the series, "The Paradox of Salmon Hatcheries."