Remembering John Harrison: Energy authority

For more than three decades, the Washington writer kept the public informed about the driving environmental issue of the times

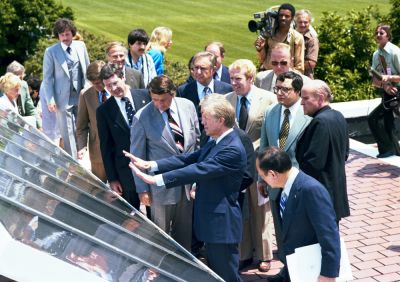

For Columbia Insight and others, John Harrison was the voice of power. Courtesy photo

By Chuck Thompson. February 10, 2025. If you wanted to know about energy in the Pacific Northwest, John Harrison was your man.

Hydroelectric. Solar. Wind. Transmission lines. Right of ways. Legal issues. Old projects. New plans. Harrison knew as much about electrifying the Columbia River Basin as just about anyone.

True to his easygoing, generous nature, he was always happy to share his knowledge.

That made him particularly valuable to Columbia Insight over the past few years.

After retiring in 2022, following a 31-year career as information officer at the Northwest Power and Conservation Council, John picked up where he’d started his career—as a reporter and copy editor at several Pacific Northwest newspapers—by joining Columbia Insight as our go-to journalist for all things energy-related.

For any environmental news organization, “Energy” is as important a beat as there is. This is especially true in the Pacific Northwest, where the Columbia River plays such an outsized role in everything from power to agriculture to recreation to salmon recovery.

John died last week of lymphoma. He was 71 years old.

A Vancouver, Wash., resident, John was a graduate of Washington State University (Pullman, Communications) and the University of Oregon (MA Journalism).

His excellence as a journalist reflected his personality. Although his commitment to environmental causes and to renewable energy was clear, he was objective in his analysis and reporting, never soft-pedaling the obstacles. By nature a kind person, with a gentle wit and sense of irony, he was not without sympathy for those who opposed positions he personally held—he understood that people with very different viewpoints could be acting in good faith. But facts were facts.

For almost a decade, he’d been an active member of the board of Friends of the Columbia Gorge, where he was known for his thoughtful contributions to board discussions.

“He was thrilled when we asked him to join the board nine years ago and his reporter objectivity helped me navigate challenging times,” said Kevin Gorman, executive director of Friends of the Columbia Gorge. “I will always appreciate his counsel and wisdom.”

With John’s passing, the region has lost perhaps its most knowledgeable energy and environmental reporter, and an irreplaceable font of institutional knowledge of Northwest power issues.