The Bull Run Filtration Project near Oxbow Park has passed compliance milestones, but locals are questioning the legitimacy of the city’s environmental assessment

New neighbor? The Portland Water Bureau has rendered images of its Bull Run Water Filtration Project. Locals see a less friendly picture. Image: City of Portland

By Kendra Chamberlain. June 22, 2023. A group of residents are raising alarm bells about a proposed water filtration plant that they say could damage local watersheds, disrupt wildlife and possibly hurt endangered species populations.

Portland Water Bureau (PWB) has plans to build a 135-million-gallon-per-day water filtration plant on a piece of farmland outside Portland, along the Multnomah-Clackamas county line.

The plant will treat water piped from the Bull Run Lake for Cryptosporidium and other contaminants before being delivered to customers in the Portland metro area.

The nearly $1.5 billion project has received a $727 million loan from the EPA’s Water Infrastructure Finance and Innovation Act (WIFIA) program.

Lauren Courter and her husband, Ian, both scientists and co-founders of the consultancy firm Mount Hood Environmental, fear PWB has downplayed the environmental impacts of the project to local and state government officials and the EPA in hopes of seeing the plant built. The duo are part of a coalition of local residents, community organizations and local commercial associations that oppose the project.

Project map showing the location of the planned water filtration facility and pipelines. Map: City of Portland

The water filtration plant, which is awaiting approval from Multnomah County, would be built on a parcel of land that butts up against the Courter’s home. The site, which PWB has owned since the 1970s, is surrounded by nurseries and was previously leased to a tree nursery.

Christopher Bowker, PWB’s Treatment Projects Compliance and Environmental Coordinator, told Columbia Insight the bureau considered a variety of site options, “knowing that this is going to be a difficult conversation.”

PWB ultimately decided on the location based on factors such as proximity to existing infrastructure, lot size and elevation.

Bowker said the elevation consideration was key to the project, to ensure that PWB can rely on gravity flow to help deliver the water down to Portland.

“The site that we ended up at ranked really well on all these different criteria,” Bowker said.

Cost, controversy

The proposal has been controversial from the get-go.

Critics have pointed out that the current proposal was one of the most expensive options that PWB considered.

And the price of the plant has steadily climbed over the past five years. The cost for the plant in 2017 was projected to be $500 million, but the estimate was steeply revised the following year when it was discovered that the initial estimate did not include the piping infrastructure needed to get the water to and from the proposed site.

The project is currently estimated to cost $1.5 billion, 200% more than the initial estimate.

Land use questions: Where’s the line between shrinking habitat and increasing industrial development? Photo: Kendra Chamberlain

Local residents are concerned that the project and its construction, which will involve hundreds of thousands of heavy truck trips down narrow county roads, could pose safety risks to the neighboring communities and the nearby school.

Earlier this year, the Gresham-Barlow District School Board adopted a resolution opposing the project’s location.

The local Multnomah County Fire District #10 compiled its own report outlining its concerns with the project, and ultimately adopted a resolution recommending denial of the proposed plant.

Determining environmental impact

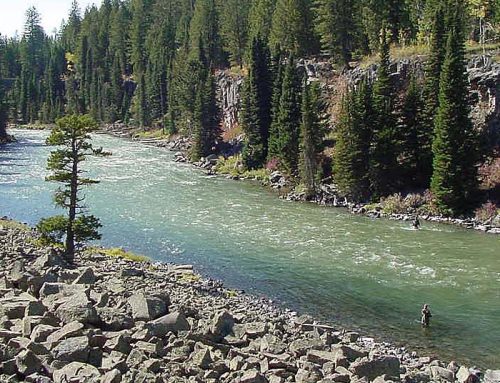

The proposed site is situated alongside the headwaters of the Johnson Creek and is in proximity to the Sandy River, a designated Wild and Scenic River. The Sandy River is also designated as a state scenic waterway and critical habitat for federal Endangered Species Act listed species.

The entire area is designated habitat and water resources of Significant Environmental Concern for Multnomah County.

Lauren and Ian Courter said they believe the environmental impacts of the project were downplayed in the City’s applications to both the county and the EPA.

Lauren Courter is a founding scientist with Mount Hood Environmental. Photo: MHP

PWB completed a Programmatic Environmental Assessment (PEA) questionnaire for its EPA WIFIA application. The WIFIA PEA is a National Environmental Policy Act-compliant assessment tool that enables an entity to complete a project without going through the lengthy NEPA Environmental Impact Statement process, which often takes a couple years and rounds of public input to complete—if the PEA determines the project will have no significant environmental impact.

The PEA questionnaire asks the applicant whether the project will have significant impacts on environmental issues such as jeopardizing the continued existence of any threatened or endangered species; or modifying, fragmenting or degrading critical habitat or biologically sensitive areas.

PWB’s application determined the project would have no significant impact across those environmental parameters.

The Cottrell Community Planning Organization (CPO) compiled a rebuttal document to the City’s PEA questionnaire. The rebuttal document pulls in state maps of endangered species ranges and habitat, as well as game habitat and water resources that could be impacted by the plant and the pipelines running to and from it.

Lauren Courter, who also serves as secretary to the Cottrell CPO, said she doesn’t think the assessment was thorough enough.

“They hired a consultant to come out and for a couple hours, they walked around a property and they’re like, you don’t see anything, and so no significant impact,” Courter said. “You know there’s more to that story.

“It’s mind blowing. You’re going to put in a 100-acre facility here—in an area where there’s the headwaters of the Johnson Creek, the Wild and Scenic Sandy—and you’re not going to do an impact analysis of any kind? You’re just gonna leave it up to the applicant to show that there is no significant impact?”

Columbia Insight asked PWB how the PEA was completed. Bowker said the EPA “led the process,” which included reviewing the PEA questionnaire responses and the supporting documentation.

“Those are pretty robust reviews that are performed. It was about a 10-month review period, so quite in depth,” Bowker said. “During that time, they have staff who are going through [and] reviewing the documentation that we’ve submitted; they’re asking followup questions if they didn’t receive what they needed to see. They’re really reviewing the environmental impacts.”

An EPA spokesperson confirmed to Columbia Insight the 10-month review period for this project involved “financial, technical and environmental reviews of the project,” which included a NEPA review and a review of the appropriate consultations with U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service under the Endangered Species Act.

The spokesperson also said that the WIFIA PEA does not require any additional public notice or a public comment period.

Contradictions about ESA-listed species

Ian Courter, who is a fish biologist, is particularly concerned about the project’s treatment of ESA-listed fish species that are present in the Johnson Creek.

“The WIFIA folks had no idea that there are coho salmon [and] steelhead that use this creek right here,” he said, referring to Johnson Creek. “Their species analysis didn’t include the most prominent keystone species for the region. How do you miss that? You’d think that would be number one. Instead, it’s not even on their list.”

A 2020 report on the project, produced by Brown and Caldwell and Associated Firms, on behalf of the City, notes that “In its lower reaches, Johnson Creek supports coastal cutthroat trout and winter-run adult steelhead among other sensitive and listed species,” but adds that “current conceptual site plans for the filtration facility show no development near these waterways.”

The land use application also notes PWB and its design team “have made significant efforts to avoid or mitigate any potential risks to Johnson Creek water quality and habitat.”

Ian Courter said that Johnson Creek also supports coho and chinook salmon and rainbow trout, which were not mentioned in the 2020 report.

“We have repeatedly seen these types of vague and often flawed explanations from PWB and their contractors,” Ian Courter wrote in an email to Columbia Insight. “They never confirmed [the] presence [or] absence of these fish species in the headwater areas of Johnson Creek adjacent to their proposed construction site. They’re also ignoring impacts to fish downstream due to water quality.

“This project will result in siltation of the stream, particularly during construction, and increased risk of chemical contamination as long as the facility is in operation. These acute risks are not acceptable because federally protected salmon and trout are already struggling to persist in Johnson Creek.”

Ian Courter has led anadromous fish studies throughout the Pac NW. Photo: Mount Hood Environmental

Columbia Insight reached out to U.S Fish and Wildlife Service with questions about the

PEA process and how it was completed for this project. A spokesperson for USFWS said PWB used FWS’s Information for Planning and Consultation (IPaC) website “to input their project location and get an autogenerated list of species that could potentially occur in the project location.” The list included eight species, none of which are fish.

The FWS spokesperson said the biologist who worked on the project had since retired, but said the service used aerial maps, knowledge of what constitutes suitable habitat, species location information from FWS files, surveys conducted by PWB’s consultants “and our own staff reconnaissance as necessary” to determine that no ESA-listed species were present at the site.

USFWS also determined that the project would not alter the hydrology of the nearby water resources in a way that would impact any ESA-listed fish species.

PWB is awaiting final approval for the project from Multnomah County. That hearing will begin June 30.

Lauren Courter said that if the project is approved by the county, the Cottrell CPO plans to appeal the decision to the state Land Use Board of Appeals.

These neighbors seem like NIMBYs who are used to having an empty field next to them. Their concerns about endangered species don’t make much sense given the location. The drinking water treatment plant is essentially a closed loop system that will not discharge to Johnson Creek or other waterways, so how exactly would it impact fish in Johnson Creek? They also claim it will result in sedimentation. The construction will be done under the 1200-C permit which requires an erosion and sediment control plan to prevent sediment from leaving the site or impacting nearby waterways. The former use of the property as a nursery likely had a worse environmental impact.

Looks like PDXstir (Portland Water Bureau) is once again trying to discredit community members (via deceptive PR) on their outrageously-priced proposal to build a mega-industrial plant on environmentally-sensitive rural land.

https://www.oregonlive.com/politics/2023/06/portland-water-treatment-plant-costs-balloon-again-price-tag-nears-2b.html